A tribute to Leopold Bloom and two different takes on motherhood: The Jewish books you need to know this month

What we’ve read and where we’ve been

Photo by iStock

Welcome to Books Briefing, your monthly tour of the Jewish literary landscape. I’m a culture writer at the Forward, and I spend a lot of time combing through new releases so you can read the best books out there.

You can shop this newsletter by visiting the Forward’s Bookshop storefront. If you shop from our page, the Forward will earn a small commission. This article originally published in newsletter form; if you want to get Books Briefing in your inbox, you can sign up here.

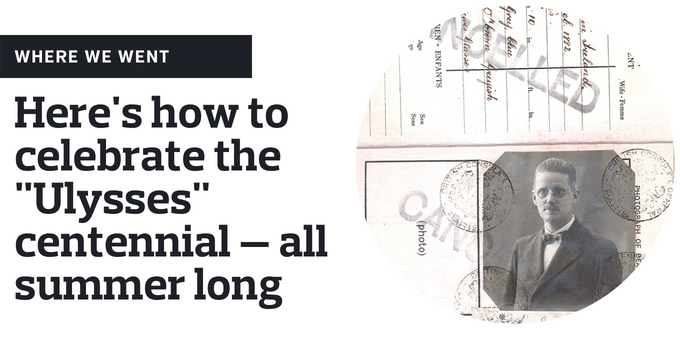

J.P. Morgan’s erstwhile library presides over a busy intersection in midtown Manhattan. But the building, now the heart of the Morgan Library and Museum, resembles a Renaissance palazzo, complete with frescoes on the vaulted ceiling, a casual Gutenberg Bible on display, and a vault for the most valuable volumes that could have been imported straight from Hogwarts.

It’s hard to know what this scion of the Gilded Age would have thought of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” a bawdy and profoundly untraditional text. (Probably nothing good.) But on the centennial of the novel’s publication, his onetime man cave is hosting an exhibit on Joyce’s writing process — and his creation of one of fiction’s most notable Jewish heroes, Leopold Bloom.

It’s difficult to make a visual exhibit based on a literary text. Fortunately, “Ulysses” left plenty of tangible paraphernalia in its wake. For the Morgan, Irish author Colm Toibin curated a collection of ephemera that illustrates the novel’s difficult passage into the world. There’s an irate satirical poem Joyce wrote to protest an Irish press’s censorship of his work. There are “legible” drafts the author sent to more hospitable printers in France and proof pages with his extensive edits in the margins. (Colm Toibin may be able to make sense of Joyce’s handwriting, but I certainly can’t.) Letters between various literati show their commitment to the novel’s success, even when a wide readership for “Ulysses” must have seemed like a quixotic idea. One of Joyce’s advocates was Shakespeare and Company founder Sylvia Beach, and the exhibit displays the sign that hung over the Paris bookstore on the day “Ulysses” was published.

Diehard Joyce-heads will revel in this exhibit. But even those poor souls who don’t observe Bloomsday will find something to love. I was particularly struck by the various editions printed in quick succession to confound British and American customs officials who censored and even destroyed shipments of this “obscene” novel. At a time when the banning of books is increasingly common in the United States, it’s moving to witness the ingenuity of writers and readers working to get challenging, even taboo texts onto bookshelves — and to confound those who wish they would just shut up.

My copy of this novel has traveled by subway, NJ Transit, and Metro North. It has crossed borough and state lines on numerous occasions. It has resided in every single one of my tote bags. Seriously, it already looks like I’ve owned it for several years because it didn’t leave my side for the week I spent reading it.

“Elsewhere,” the sophomore novel from Jewish author Alexis Schaitkin, takes place in a tiny, Teutonic mountain town (lots of alpine flora, lots of strasses) where the cheese is fresh, the children are neat little musical prodigies and life is pretty much perfect. Except for one thing: Every once in a while, a mother simply disappears, fading out of the world without a trace. The townspeople don’t know how this happens, or why. But they accept it as a necessary “affliction,” a sacrifice they make in exchange for their Edenic lifestyle and seclusion from the outside world, a shadowy realm known simply as “elsewhere.” Schaitkin’s protagonist Vera loses her mother at the age of five. But as a young woman she unhesitatingly embarks on the dangerous project of motherhood herself. Only when she begins to anticipate her own disappearance does she escape to “elsewhere,” making the wrenching choice to lose her family instead of losing herself.

Years later, when Vera finally returns to her birthplace, she marvels at the reverence accorded mothers, even as their disappearances are accepted as a fact of life. “They did not exalt mothers as we did here,” Vera remarks of the outside world. “But then, nor did they sacrifice them.” The universe of “Elsewhere” is a fairy-tale one. But the novel asks if Vera’s town is so different from a society that valorizes mothers yet, by offering abysmal social benefits and dwindling access to reproductive healthcare, treats their lives and labor as disposable. What would a world look like that truly valued its mothers? “Elsewhere” doesn’t have answers, but it poses the question eloquently. Get a copy for yourself — and maybe one for your mom.

Most readers know Isaac Bashevis Singer first as a storyteller and second as a poster boy for people who like to brag about the number of Jewish Nobel winners. But he was also a prolific writer of essays, which found their audiences on the lecture circuit and in the pages of the Forverts, where he used a variety of pseudonyms in order to publish frequently without appearing to dominate the paper. These short, sprightly pieces, many of which appear in English for the first time in this collection, could have been written yesterday. Singer’s musings on the strengths and limitations of Yiddish as a literary language are especially moving. “I could not convey in Hebrew a conversation between a boy and a girl on Krochmalna Street,” he writes, referring to the Warsaw neighborhood where he grew up, and where some of his fiction is set. Yet, he remarks, no one could write “War and Peace” or “Crime and Punishment” in Yiddish, simply because “no counts, ranking officers or even university students used Yiddish in their everyday life.”

And while the particular appeal of Yiddish may be of most importance to Bashevis Singer scholars, I cannot let this newsletter go by without mentioning his knack for humor pieces. In one, he imagines reviews of the Ten Commandments as composed by cranky modern critics. From the communist: “One may not steal, but one may exploit workers. Were Rockefeller, Ford, and Morgan not thieves?” From the historian: “Mr. Moses has copied word for word from the laws of Hammurabi, who lived 4,000 years ago.”

And, of course, from the Jewish magazine: “Not a single Jewish leader or organization is mentioned in these ‘commandments.’ As a matter of fact, Mr. Moses completely ignores the Jewish question and the problem of antisemitism.”

Aviva Rosner, foul-mouthed singer-songwriter on the brink of mainstream fame, is drinking fresh-pressed juices. She’s eating organ meat. She’s abstaining from alcohol, caffeine, gluten and dairy. She’s practicing yoga and undergoing acupuncture. She’s doing everything she can to have a baby.

Well, almost everything. Pretty much everyone around Aviva is encouraging her to pursue assisted reproduction — her friends, her doctor and even her mother, who treats Aviva’s failure to conceive as a personal betrayal of the Jewish people. But Aviva views the fertility-industrial complex with skepticism, objecting not just to medical procedures she finds intrusive but also the idea that wealthy women can and should pay to bypass their own bodies. The novel follows Aviva as she launches her fourth album, develops a serious obsession with fellow Jewish songstress Amy Winehouse and fends off her mother, a giver of gifts like books titled “Are YOU the Reason You’re Not Getting Pregnant?” All the while, she’s deciding to disregard her own reproductive instincts or give up on the family she’s envisioned for herself.

Aviva’s righteous anger can be trying: One wonders how exactly the performance of “heart-opening” yoga rituals and consumption of green smoothies are more virtuous avenues to pregnancy than IVF. “Human Blues” lacks the nuance that made Albert’s previous novel, “After Birth,” such a critical success. But it’s still a noteworthy addition to the growing pantheon of books on ambivalent motherhood: Lydia Kiesling’s “The Golden State,” Rachel Yoder’s “Nightbitch” and pretty much Elena Ferrrante’s entire corpus. Books like these turn a critical eye to the experiences of women who are already parents. “Human Blues” asks if women who want children should be expected to procure them at any financial or emotional cost.

Dahlia Adler has made her literary career rewriting archetypal teen experiences to feature queer protagonists. When a Texas high school’s quarterback dies at the beginning of “Home Field Advantage,” the coach replaces him with a female football prodigy, Jack — a decision that proves seriously unpopular with a team and cheerleading squad as committed to gender norms as their state’s legislature. Only Amber, an ambitious cheerleader who also happens to like girls, thinks Jack deserves acceptance and support. But standing up for her crush might mean losing the squad captaincy she’s been dreaming of for years. You can probably guess who wins the homecoming game in this extremely safe-for-work romance. But while Adler provides the happy ending I craved, she never gives way to fantasies of acceptance. In “Home Field Advantage,” there’s no guarantee that Amber and Jack will find a more tolerant world — just friends and lovers who will help them cope with this one.