In Poland, a return to the scene of an unspeakable crime

A journey to Jedwabne, site of the massacre of 1,600 Jews, kindles both anger and a sense of redemption

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

When I was a boy, I often pondered the fate of my European relatives on my mother’s side. I knew my family had originally been named Piekareski and they had lived for many generations in a little town called Jedwabne, near Białystok in northeastern Poland. I knew that my grandfather Samuel had been smuggled out of Jedwabne and Poland by his doting mother at a very tender age. She had disguised him for the journey by dressing him up as a little girl to prevent him from being turned back at immigration as an able-bodied boy to be eventually conscripted into the Polish army.

At Ellis Island he was given a banana, a fruit he had never seen before, by a well-meaning immigration official — and he never forgot his attempt to eat it, skin and all (and he never, ever ate one again).

Besides wondering why Piekarski had been changed to Goldman, his new American surname (that’s less Jewish sounding?), I used to ask my Grandpa, a proud, feisty, pretty much self-educated man who had raised a mighty family and whom I loved dearly, what became of the Piekarskis, and why, in fact, we had no more living European relatives on my mother’s side of the family?

“They took all the Jews in Jedwabne and burned them all up in a barn during the war, that’s why,” he said. “Those dirty mamzers, those dirty Polacks!”

Cringing at this horrible story, and shocked by my normally mild-mannered grandpa’s intolerant language (weren’t we also of Polish descent? And what exactly set us apart from our non-Jewish neighbors in Jedwabne that would justify such an atrocity?), I filed this information away for many years in the back of my mind under the heading “Subject for Further Investigation.” It especially galled me, Europhile that I am, that in an era growing up in which the heritage of every conceivable ethnic group was being celebrated, mine seemed to have been definitively, literally cut off at the roots by what happened in Jedwabne, details of which were vague.

This story of the burning barn was like an unconfirmed rumor that circulated quietly among the Goldman family. My parents, Adele and Murray, actually made a pilgrimage to Jedwabne some years ago, but brought back no fresh information. Before he died, I’d press my grandpa repeatedly for more stories about Jedwabne, a town that he seemed to recall vividly and with much obvious affection, and although he had no more details of this Slaughter of the Innocents, he would obligingly regale me with warm and endearing tales of his uncle who drove the Polish stage coach, his cousins, the Noziks and their extended family, and other precious memories he took with him when he left Poland shortly after the turn of the century.

Thus it came as a total revelation, an unexpected fiery bolt from the skies, when I opened The New York Times one morning in 1996 and discovered a letter to the editor from one Ty Rogers describing the Jedwabne pogrom in authoritative detail. He had a date for it, too: July 10, 1941. And he mentioned a memorial standing in the town that erroneously ascribed the killings to the German Nazis alone.

Stunned, I tracked Ty down, called him and introduced myself. It turned out he was a fellow landsman whose grandfather had also come from Jedwabne; he had been there fairly recently, had done some investigation into the facts of the pogrom, and most important, was in possession of a yizkor book from a Rabbi Baker, another landsman now living in Israel, who had left Jedwabne in the ’30s, and who had painstakingly gathered together all known (at the time) survivor’s accounts and photos of the community.

The yizkor book also included a list of all the Jews burned in the barn after being cruelly tortured on that fateful day. Chillingly, I found both my grandpa’s family’s name and his cousin’s family’s name on that list. Thanks to Ty, a young lawyer brimming with energy and a dogged determination to further share the truth about Jedwabne with the world, I made copies of this book for my family, and it circulated among my parents, uncles, aunts and cousins like samizdat literature.

Ty and I became good friends — I actually attended his late bar mitzvah a few years ago — and both he and our wives bonded by going to see the Klezmatics play at the Knitting Factory together shortly thereafter. He and his lovely wife Elizabeth both came to see me play as well with my own band Gods and Monsters at the Mercury Lounge not that long ago.

Then, another revelation — the publication in Poland of NYU professor Jan T. Gross’s excellent and informative book “Neighbors,” which provides an even more thorough account of the massacre of an estimated 1600 Jews, and which definitively implicates the local Polish community of Jedwabne in the crime — its inescapable conclusion being that, indeed, here was a case of neighbors killing neighbors.

So it was with amazement last spring when Ty told me that the Polish government had actually invited the surviving members of the Jewish families massacred in Jedwabne to attend a memorial service on the 60th anniversary of the killings, in which the Polish president himself would actually formally apologize to the Jewish people on behalf of the Polish nation for the crimes committed on that day. My own extended family urged me to go as their Designated Mourner (thank you Wallace Shawn), citing age and work obligations as the main obstacles preventing them from traveling with me.

But questions remained. Under much pressure from the Catholic right wing in Poland, the precise language to be inscribed on the memorial plaque, which was to have laid the blame for the murders squarely upon the Poles, was bowdlerized to read as just a simple declaration that the murders occurred. (I’m reminded of Lenny Bruce’s routine in which a Jew, attempting to absolve our people from supposed collective guilt in the death of Jesus, leaves a confessional note in his basement: “I did it! Signed, Morty.”). This emendation did not sit at all well with the group of surviving landsmen and women, who, through the miracle of the internet and Ty’s indefatigable attempts to locate and connect us all, had swelled to about 100 strong around the world.

Every week brought a new flurry of emails from Ty, sometimes several a day, transmitting the latest news about the memorial event to come. Would we accept the compromised language on the memorial plaque? Should we boycott the ceremonies instead?

A secondary issue was accommodations — the original offer from the Polish government to put us up in a hotel at their expense for a week was scaled back at the last minute to covering two days of hotel only, outraging many of the group who had purchased non-refundable airline tickets based on the original invitation. The official explanation was the unforeseen costs of housing such an unwieldy group, which had grown larger than originally estimated. Many in the group believed it was a late attempt to discourage people from coming at all, especially once our unhappy feelings with the new inscription were made known.

After much debate, most of us decided to come anyway. At the very least, to pay our respects to the martyrs of July 10, 1941.

Having bought one of those non-refundable tickets, I flew to Warsaw on the evening of July 4 from JFK.

Arriving bleary-eyed from the eight-hour flight, I was picked up by two charming young female Polish foreign office guides, and deposited in the eerily deserted Parkowa Hotel, the official government residence directly across from the Russian embassy. Entered only through a gate guarded by several young soldiers, this ’50s-style hotel was to serve as the rallying point for our group; it was situated in the foreign embassy enclave not far from downtown Warsaw, next to a sprawling park.

I had elected to spend the next couple of days in Krakow since the group wasn’t really scheduled to gather until Sunday. I particularly wanted to visit the annual Jewish Heritage Festival there. After dinner in the empty hotel restaurant (the food in Poland was excellent throughout my stay) and a restless night’s sleep, I left by train early the next morning for Krakow.

I had been to Krakow once before on some days off from a lengthy tour of the Czech Republic, and again found the city as beautiful and uplifting as ever. Warsaw had been leveled by the Germans; Krakow remains today in all its magnificent Old World splendor. The Old Town section, while dotted with Benettons and McDonalds, is one of Europe’s jewels, akin to the Old Town in Prague (another city that escaped the bombing). The Kazimierz old Jewish quarter, which is ground zero for the Jewish Heritage Celebration, lives again, thanks to Jews who come from all over the world to visit, and thanks to the Ronald Lauder Foundation, who restored the ancient building. As I wandered through the twisting little streets and leafy byways on that sunny Friday afternoon, I truly felt I had come home.

In the cozy, warm dining room of the Klezmer-Hois, one of the small Jewish-themed hotels on Szeroka Street, I spoke to Janusz Makuch, the visionary director of the Jewish Heritage Festival. Outside, families and couples ate picnic-style at little tables beneath the green trees that surround the hotel, right next door to a superb new vegetarian restaurant.

“I remember organizing the first festival in 1988,” Janusz told me. “And it was the beginning. I remember there was only one Jewish museum then on Szeroka Street, and no real restaurants. There was nothing really. Then the people I wanted to invite to Krakow started to come, like Andy Statman in 1992. He’s a genius, of course. The audience was expecting this little boy with peyot playing, you know, ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ And he suddenly started from Coltrane, and began to play this free Jewish music. It was amazing.”

“We had seven, eight thousand people last year dancing in the streets of Kazimierz on the last night of the festival — in the rain! And not all of them Jews, of course,” he said. “Since Jews have given so much to Polish culture, it’s only natural that the Polish people here would support our festival so strongly. It’s a lost world for them to discover, like Atlantis.”

“It’s very, very difficult to preserve the memory of the Jewish culture in the cemetery here,” he told me. The cemetery he referred to was Poland itself, once home to 3 million Jews. “But here at the festival, here in Krakow, this is a living culture, a living tradition, part of a long, long process. And I strongly believe in the culture, that people like me, Jew and non-Jew, can sit around the table here, can talk, can drink and eat, can play and enjoy our common time. Doesn’t matter who is Jewish and who is not Jewish. We’re all together in this common, this very small world.”

Indeed. Saturday night the streets of Kazimierz were packed with thousands upon thousands of revelers exalting in the atmosphere of a rock concert. I met Jews who had come from all over the world (including Jan Gross of “Neighbors” fame and his girlfriend), but I think it safe to say that the majority of celebrants were Polish gentiles standing shoulder to shoulder with their Jewish music-loving counterparts, digging the rapturous vibes together.

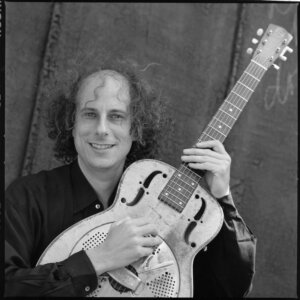

I had an emotional reunion myself with trumpeter/composer Frank London and saxophonist Greg Wall, the leaders of Hasidic New Wave, the incendiary jazz-rock group who closed the festival, which also featured outstanding modern klezmer ensembles such as Brave Old World and Satlah. I had toured with Frank and Greg and their at-that-time-Israeli rhythm section in 1993, barnstorming one-nighters all over Europe on the Knitting Factory-sponsored JAM Tour (Jewish Avant-Garde Music Tour) with my original live solo guitar score to accompany the 1920 silent film “The Golem.” Now Frank and Greg asked me to sit in with them for their closing number.

After a rousing set that included a thunderous Senegalese drum ensemble augmenting the core Hasidic New Wave group, I was introduced by Greg as “an old friend” (I played on their first album) and took the stage with my slide guitar in hand. To stand onstage and play with them on their final number, overlooking the tumultuous throngs of ecstatic people in the central square, was an awe-inspiring dream for me. I took a bow with them and, choked with emotion, retired to my hotel shortly afterward, the strains of Frank’s trumpet and Greg’s sax continuing to echo ghostlike on the empty streets of the Old Town, wafting over on the night breeze from the festival closing jam session down the road.

I returned to Warsaw the next morning on an old train jammed with young people, many of whom had come from all over Poland for the festival. Watching the green meadows flash by as we approached the city, I reflected on the beauty of the natural landscape of Poland, and how it had been sullied by the deaths of millions of Jews who had lived there. Were these the same verdant vistas the deportees saw on the way to the camps?

It was difficult to reconcile the incredible ecumenical spirit I felt in Krakow with the ghastly history that underlay the fields surrounding us as the train sped on to Warsaw. I am a tremendous fan of the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer. He’s my favorite writer and I have read every one of his books, including his last work “The King of the Fields,” a tremendous work of historical reimagination that takes place in a pre-Christian, pre-Jewish Poland. Here were those same fields, drenched in blood. Yet they appeared to me now as fresh, innocent and eternal. And, as the chattering children spilled off the train at the Warsaw station, I felt the spirit of hope for the future of Poland continue to stir in my breast.

The Parkowa Hotel was now filling up with the new arrivals of landsmen and women. From Israel, South America and Mexico they came, from New York, Detroit, Albuquerque and California. They clustered in groups from the airport, and we introduced ourselves and embraced each other in the marble lobby all day. Talking excitedly in Yiddish, Hebrew, Spanish and English, we brandished faded snapshots of relatives left to die in Jedwabne, such beautiful tender faces in the old photos, and in the lobby.

We told our family stories to each other well into the night, stopping only for a short interview with German TV. As they filmed us outside the Nozik synagogue in downtown Warsaw in the fading twilight, the interviewers from that network, ARD, seemed almost relieved that for once this was not a story about German bestiality toward Jews.

Monday morning, I took a stroll in Warsaw’s own Old Town, rebuilt brick by brick after the war in a very realistic recreation of the original cityscape, in the company of an elderly Israeli couple, Tovah and Jacov Tal. I had bonded with them the night before, and had listened, spellbound, as Tovah had described her peripatetic upbringing, which took her from Poland by way of Germany to Shanghai before she finally settled in Israel with Jacov, a former officer in the Israeli Air Force.

I quizzed her closely about her memories of living in China — my first wife was a Chinese woman who had studied on a kibbutz in Israel before converting to Judaism, and I had recently recorded an album of Chinese pop from the ’30s. And of course I quizzed her about her connection with Jedwabne. Her husband’s family was from Palestine, and had lived there for over 150 years. Jacov told me how he flew on the famous air mission during the Six-Day War that completely took out the Egyptian Air Force.

In the windows of the tourist shops in the cobblestoned streets of the Old Town we noticed puppets and figurines of Hasidic Jews in black coats with peyot and beards. Memento Moris, perhaps of a vanished culture, one that had seemed to flourish again so vividly Saturday night in Krakow.

Back in the hotel, I encountered Rabbi Baker, an Israel-based rabbi and one of the prime movers in bearing witness to the terrible truth of Jedwabne. I had first met him several years earlier at a Yahrzeit ceremony for the landsmen and women of Jedwabne held in a shul in Brooklyn, to which Ty had invited me. Now back in his native land, he looked older and frailer than he had before but still alert and dignified.

There was also a fiery young poet from Buenos Aires named Laura Klein. Chain-smoking furiously and drinking cup after cup of coffee, Laura was determined to read a statement she had prepared for the early evening news conference, really the only chance the families had to make any kind of official statement to the press as the ceremonies in Jedwabne the next day had been planned down to the minute and, outside of a scheduled address by Rabbi Baker, no spoken contributions from the group had been requested (or were in fact desired).

Perhaps the Polish authorities (and the official Jewish leaders) feared an embarrassing situation should one of the group decide to protest in front of the international media covering the ceremony by bringing up the issue of the controversial circumscribed memorial inscription that did not specifically blame the Poles as the murderers. Or to protest the humiliating recent exhumation of the mass grave in order to count bodies and body parts to determine the precise number of Jews killed there.

As if that in any way could change the reality of what had happened that day in Jedwabne.

As usual, when any group of Jews gathers anywhere to discuss anything, they will never reach a total consensus. When we entered the official government reception house that evening where our group’s news conference was to be held, I overheard one elderly woman from our group shake her head in disbelief and say loudly to herself (and for all to hear), “I don’t want any part of this! These people here don’t speak for me; these are not my feelings about this.”

After a formal statement by our Polish hosts, where we were introduced to the government officials assembled there who had been working and planning the Jedwabne memorial for some time, and a short repast of drinks and canapes, we trooped downstairs to meet the press, which, significantly, was mainly only the Polish media; most of the foreign press in Poland had not been invited.

One by one our six designated speakers addressed the crowd, beginning with Ty Rogers; he more or less socked it to them there by relating our anger at the truncated memorial inscription and our insistence on putting the blame for the massacre in Jedwabne on some of the Polish people living there, not the Germans.

The Polish journalists, cameramen and officials looked distinctly uncomfortable as they listened to our group, as one after another of our speakers reiterated the same points, each address seemingly angrier and more grief-stricken than the last. These jeremiads culminated with Laura Klein’s dramatic and emotional address entitled “Forgive Yourselves,” which she prefaced thusly:

“I would prefer to read this text tomorrow, in Jedwabne, at the official ceremony. But we, the descendants of the Jewish families slaughtered in 1941, were not allowed to speak there, face to face to the descendants of our Polish neighbors,” she said. “We are not needed for their ceremony of public repentance — we have come to confirm that our voices are absent, and to invite the Poles to keep their contrition and their shame to themselves.”

Her address went on to invoke the words of Primo Levi written after Auschwitz, finishing with a poem she had written herself as a suggested prayer for all Polish people to recite daily, an intense indictment of the actions of their forbears. Strong stuff, and undeniably cathartic, whether you agreed with her or not.

When she had finished, there was a supercharged, unbearably claustrophobic atmosphere in the room. The spell was broken finally by a short, upbeat speech by Rabbi Baker’s son-in-law which called for reconciliation with the Polish people and a call to move forward together in a positive direction.

The press swarmed forward to take pictures and ask for comments from our group spokespeople.

We returned to the hotel with some sense of satisfaction that the voices of the surviving families had been heard, directly, at last.

On Tuesday, we arose to an autumnal gray morning to leave on the bus for Jedwabne at 7 a.m. As we traveled the two-and-a-half hour journey, the skies darkened, the wind picked up, it grew noticeably colder, and it began to rain heavily. After the unseasonably warm and humid summer weather we had enjoyed in Warsaw, this was a funereally appropriate atmosphere for the memorial.

Gazing out the bus window, I moodily saw the same lush landscape I had enjoyed on my train ride back from Krakow transformed in the misty morning half-light into a primeval forest inhabited by malevolent creatures and mournful spirits.

Suddenly, a voice broke my gloomy reverie: “Excuse me, are you the man that is related to the Nozik family? We are some of us living in Israel now; you surely must be our cousin!”

It was the voice of a kindly, sympathetic soul, a radiant elderly woman named Jafa Azaryho. I went back to her seat and met two couples, both Nozik-related, both living in Israel, one couple in Jerusalem, the other in Tel Aviv.

“And we remember your mother’s cousin Max; he used to send us food when we were first living there, all the way from America in 1951,” she said.

I couldn’t believe this. I had direct kin here I never knew existed!

Tears welled up in my eyes as they showed me pictures of the Nozik girls in turn-of-the-century Jedwabne. I felt some relief, some joy, but also much anger as we wound down the Polish highway, past signs advertising chainsaws, through the town of Łomża where the Jewish ghetto in the region stood, finally halting in a muddy field outside the market square of Jedwabne.

Government helicopters hovered in the distance overhead. There were security people and soldiers everywhere. As we stepped warily off the bus, we saw throngs of curious onlookers lining the streets of Jedwabne, many with staring, stony faces and hard eyes. How dare we come back to their town? What did they have to do with this killing in 1941?

I have to admit I was a little bit scared.

“Look at this poster! How disgusting.”

One member of the group pointed to a paper flyer affixed to a lamp post, which basically said in Polish, “We didn’t do it; it was the Germans; this ceremony is a lie.”

“They should have at least taken these down,” someone in our group muttered.

“This way!” We were jostled hither and thither up the street, into the town square, past the massive Catholic church. Two parishioners in front of the church held up a big banner with a quote from a famous Polish poet to the effect that the truth shall set you free, and that this memorial ceremony was not the truth.

A drunken village lout ambled by and giggled inanely, then shouted an epithet at our group. We didn’t have time to react; we were swept up by the tumult, it was raining harder and a chilly wind was blowing through Jedwabne.

I looked around as we swept past the squat mustard yellow and brown houses, and gazed at the narrow twisting side streets. I could easily project myself into the madness of 1941, could easily imagine being chased and hunted down in these rude alleys.

I was dragging my guitar case down the street with me. It weighed a ton, the cross I bear throughout my music career, a steel reinforced flight case to prevent the airline baggage handlers from playing basketball with my guitar.

Two years earlier, Swiss International Air Lines charged me an extra $500 overweight charge because of my heavy guitar cases to fly from Zurich to play a festival in Tel Aviv. “Are you trying to get the money back you just paid back to the Jewish people?” I asked the flight agent sardonically.

I want to play in Jedwabne, I thought. I want to exorcise the ghosts of my ancestors and say a prayer, my way, for my people.

I felt a kinship with Laura. Unlike her, I didn’t reject reconciliation with the Poles. But I did feel as if I had been prevented from giving voice to my feelings at the official ceremony, which was of course being scripted by politicians on both sides.

“Who are you? I never heard of you or your music before” one of the Orthodox rabbinical associates had said to me snidely earlier that morning back in the hotel, attempting to put me down as someone not worthy to participate in their memorial service. Everyone had their own agenda here.

“I played with Leonard Bernstein, and Captain Beefheart and Jeff Buckley and Lou Reed. I play my own music all over the world,” I said, and showed him the International Herald Tribune’s profile on me that had run that January.

He turned away dismissively. “In my law, you’re disturbing the dead if you play here,” he said.

“I doubt that,” I retorted. “My family had many musicians in it. I’m sure they’d approve.” To me, music is the healing force of the universe. Far more effective than words, words, words. It cuts across all national boundaries, religions, age groups. Think of the festival in Krakow.

A Polish security guard seized my guitar case and demanded that I open it. Just an acoustic guitar, sorry.

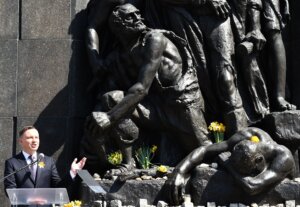

Then it was time for the Polish president to speak.

To his credit, his speech firmly put the blame on the Poles, not the Germans. He was looking to the future and to building better relationships with the Jewish community. He seemed like a mensch.

We moved to the memorial itself, in a vast field near the old Jewish cemetery. There were many, many young Polish people in the crowd sitting with our group of surviving families, looking sorrowful, attentive and sympathetic. One of the blonde youngsters handed my elderly Israeli cousin a cup of water.

These children seemed the flowers of the nation, and perhaps the only hope for the future.

When I first started playing in Germany years ago, I had severe doubts about my endeavor.

I remember my grandpa describing how he refused to set foot on German soil after the war, refusing to leave his cruise ship when it docked in Hamburg on the Grand Tour. “They didn’t bomb enough here,” he said. “They didn’t bomb enough.”

I reject this attitude, as well as his intemperate language about the Poles all those years ago. I understand where it came from. But I won’t buy into it.

We placed stones on the memorial, and blue yahrzeit candles. I started to cry again.

Cantor Jacob Malowany from the Fifth Avenue Synagogue sang a prayer to conclude the ceremony as the wind whistled in our ears. His voice reached to the heavens and echoed in the surrounding fields. His voice actually cracked, as he sobbed with grief.

Now we moved into the graveyard. I waited for the prayer service to conclude.

And then I took up my guitar and played — at first tentatively — “Hatikvah.”

Friends from the group, examining the gravestones, turned and looked at me; warm smiles broke out all around.

Gathering strength, encouraged, I played “Adon Olom.”

This hymn in praise of the Almighty moved through the cemetery like a wandering spirit. Strangers from all over stopped to listen, touched by the old song.

Nobody asked me to stop.

I continued, wandering through the graveyard to say Kaddish, in my way.

My guitar was finally drowned out by the noise of the international press helicopters departing overhead.

The group moved backed to the bus, ready to return to Warsaw. The media caravan packed up, ready to move on.

I decided to stay in Jedwabne for a little while longer, with Laura Klein and the documentary filmmaker Slawomir Grunberg, the director of the film “Shtetl.” We wanted to see for ourselves a bit of the town, without the crowds and the media circus there.

The parishioners were still standing rigidly in the rain holding their banner of denial in front of the Catholic church. No representatives from their organization accepted the invitation to attend the memorial ceremony. Instead, they were urged to boycott it by the local priest.

Laura knocked on the door of the ancestral house of her family, the Grandowskis, a small yellow house off the central square near the church.

The door opened and a young Polish woman with her son excitedly invited us in. She spoke good English; she had lived in New Haven for some years. Unbelievably, we discovered that she is Laura’s third cousin. Her family came back to Jedwabne after the pogrom as converted Catholics, to reoccupy the family house. Yes, she was a Grandowski. There was a large tapestry of the Last Supper hanging on the wall of the house.

We went back outside. The church bell rang — 3 p.m.

The time 60 years ago when the burning of the Jews of Jedwabne began.

No bells were heard ringing in the local church that day.

I picked up my guitar and begin to play again, in front of the church. The rain beat down steadily.

“And I played my guitar, through the night to the day, urn, turn, turn again.” I sang Bob Dylan’s “Percy’s Song.” “And the only tune my guitar could play was, ‘Oh the Cruel Rain and the Wind.’”

The next day the sun was shining once again. I said goodbye to all my new friends in the lobby of the old hotel. Especially to my dear, newfound Israeli cousins. Next year in Jerusalem, maybe?

Warsaw looked splendid to me, the Old Town shimmering in the midday sun. I ran into some more new friends there, journalists on a last-minute shopping spree, before heading to the airport. Buying last minute tchotchkes, including those bewhiskered Hasidic dolls.

Next year in Krakow, definitely.