750 artifacts of the Holocaust, each with its own tale to tell

At the Museum of Jewish Heritage, ‘The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do’ lacks focus, but spotlights powerful stories

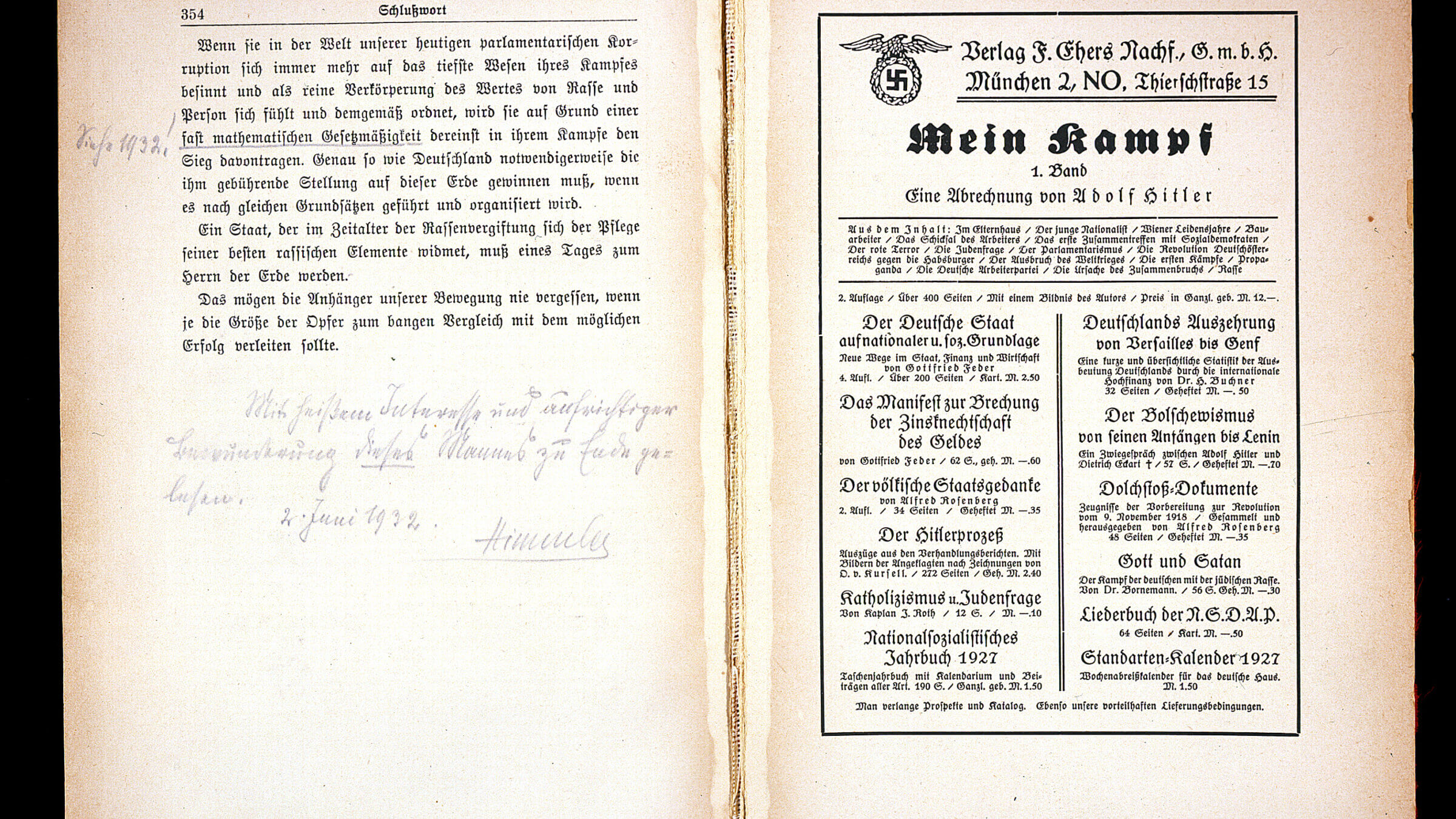

The second volume of Heinrich Himmler’s copy of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf.” Courtesy of The Museum of Jewish Heritage

Walking into “The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do,” the new core exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Lower Manhattan, visitors are immediately confronted with the enormity of the exhibit’s prompt, even if they already knows the broad strokes of the subject.

Down a dark corridor, photographs of Jewish families with their pets, a Krakow football club, a Hebrew class at a girls’ school in India, all from various decades of the early 20th century, line the walls. Piped through this narrow ingress are Yiddish songs and children singing “Hatikvah.” A screen shows black-and-white footage of shtetl life. And, if you have your earbuds in for the audio tour, the voice of actor Julianna Margulies informs you that “by the spring of 1943, many of the people you see here had been murdered.”

The journey begins with those weighted words and, through a vast array of artifacts, does its best to tell a unified story – one that, in its immense scope, at times feels hazy, somehow less than the sum of its many, poignant parts. Curated by Holocaust historians Michael Berenbaum and Judy Tydor Baumel-Schwartz, the exhibition is ambitious, vying to explain world Jewry, Jewish customs, the history of global antisemitism and – in the vestibule following the diaspora section — the happenings of one month in the year cited in the Margulies’ narration: April, 1943.

That month, as we see through wall text and objects, the Warsaw Ghetto rose and Auschwitz installed crematoria. In America, Ben Hecht’s stage pageant, “We Will Never Die,” which cried out for the Jewish people, played in Washington, D.C. As a smug photo of American and British diplomats documents, the Bermuda Conference convened and decided not to act on behalf of European Jews. It was also Passover and, as an out-of-the-way portion of the exhibit labeled “Also in April 1943” indicates, the “Netherlands Liquidation” was ongoing, Libyan Jews were deported and doctors at Ravensbruck experimented on inmates.

While this was an eventful month, why choose to lead us there directly after a look at Jewish life before the war, skipping several years? The suspicion that I missed a room only heightened as I went from the specificity of April ’43 to a hexagonal space devoted to the broad context of who Jews are. Here there are ketubot, ritual objects and, on the other side of a wall explaining different Jewish languages and streams of Judaism, a gorgeous sukkah illustrated with biblical scenes. The gallery shows the vibrancy of Jewish life we’ve seen – and are about to see – decimated. But this primer on Jews feels like a detour before striking the theme proper: a hatred less concerned with how Jews lived and prayed than conspiracies about their influence.

The exhibit hits its stride in the following space, with a wall-mounted timeline of Jewish expulsions dating to the Middle Ages, various copies of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” and political cartoons of Alfred Dreyfus, summing up the history of the Oldest Hatred – and the Jewish response to it. From there we are placed back on track with the preamble to World War II: The Great War and the rise of Nazi ideology. We then move chronologically through the stages of the Holocaust.

We learn about the Nuremberg Laws; we see the certificates of a disbarred judge and racial determination tables, disturbing swatches of skin tone colors and irises. We see a Torah rescued during Kristallnacht, and the cookie box the c0-owner of Seelberg Keks cookie company took with him on his way out of Europe. Finally we see artifacts from the ghettos, killing fields and concentration camps (yellow badges, a family welcome mat used for warmth near a mass grave, striped uniforms).

The objects are compelling, particularly when we know to whom they belonged. You can see Heinrich Himmler’s personal copy of “Mein Kampf” (and a cape and dagger he wore). There are prayer shawls and tefillin recovered at Ponar and Miropol and a Haggadah secretly used for a secret Seder at a labor camp. One artifact likely to draw the eye is the shirt of Tuvia Bielski, a Belarusian Jewish partisan leader immortalized by Daniel Craig in the film “Defiance.” It’s the intimate objects – ones that can be traced – that humanize events, alongside the testimony of survivors printed on the walls or played as videos.

But I found the displays dizzying when married to the audio guide, which was meant to unify the experience. It’s not always clear whether what Margulies is speaking about is an item on view – somewhere – or merely visible on your phone as a thumbnail. I spent a large part of my tour trying to find corresponding numbered symbols on vitrines or walls to play the next part of the tour. I ultimately gave up, choosing to experience the already overwhelming objects on their own terms — which may be the best approach.

Taking a step back from the scholarship and the impressive interactive maps of pogroms or the “Holocaust by Bullets” and the countless people whose lives we glimpse through artifacts, I wondered if the exhibit could prove challenging for a school group or a tourist less familiar with this history. Surely some museum guides will do a wonderful job taking students around, giving them a crash course without the aid of the audio tour. But what about the family that stops off in between their trip to Ellis Island or the Statue of Liberty? Would the experience be edifying, or information overload? The overall effect is daunting in a way that the previous core exhibit, on Auschwitz, wasn’t, by virtue of its being largely delimited to one camp complex, and the tracks and cattle cars that led there.

With the full benefit of the museum’s holdings, the exhibit often lacks focus and coherence. But that’s only when it’s viewed as a survey and experienced in a linear way.

In remarks before the opening of “What Hate Can Do,” Berenbaum said he believes in a “storytelling museum,” and went on to list some of the many stories on display. There are objects that testify to the life of a 10-year-old boy “buried alive” to survive the mobile killing units, the story of a sonderkommando in a concentration camp, the story of a Jewish American spy who wore both his country’s uniform and the enemy’s, even the story of the complacent American officials who acted or failed to act to save Europe’s Jews from annihilation.

If one takes the time, approaching each object, watching the testimony of survivors, and reading the names, the individual stories come through. And that’s what matters.

“The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do” is now on view at the Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. Tickets and more information can be found here.