How a Black, queer, Jewish artist uses her work to change the world

The art of 24-year-old Ayeola Omolara Kaplan confronts racism, antisemitism and misogyny

Courtesy of Ayeola Omolara Kaplan

Long before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Ayeola Omolara Kaplan was thinking about how to illustrate the need to protect reproductive rights.

Finally, the image for what would become “Abortion Justice is a Jewish Value” came. A garland of flowers interspersed with Hebrew and English text surrounds several women. They are Black, white and brown. They have caramel curls and mermaid-green tresses. One wears a Star of David, another a hamsa.

“There are moments where I feel really upset about abortion rights being taken away, and the idea that there are more rights that they could take away. I feel a stronger sense of urgency than ever before to create and act. That’s how I view my role as an artist; as pushing back,” Kaplan, a digital artist, said about the piece. The work was commissioned by the National Council of Jewish Women. Proceeds will go to organizations that provide abortion access and health care.

At 24, Kaplan, a Black, Jewish and queer artist, is making a career out of creating pieces that explore identity, class and spirituality. Whether she is depicting the idea of reparations as a form of teshuva (repentance) or imagining Queen Vashti and Queen Esther as rulers over a realm devoid of misogyny, Kaplan sees her art as a means of self-defense in a world that can feel fractured and fraught.

“We live in a society where the media being offered up for us to consume keeps us in a state of anxiety and makes us believe that everyone around us is a problem in some way. I feel that creating artwork based in love and collective growth is a form of fighting back against despair,” Kaplan said in a Zoom interview from her home in Atlanta.

Kaplan says she started drawing as soon as she could hold something in her hand. Sometimes, it was a pencil or pen; sometimes, a paintbrush.

“Art was a language in my house,” Kaplan said. “My grandmother, my bubbe, would write me notes with little images on them. My aunt, Ameenah Kaplan, is a Hollywood director who helped create the Disney ‘Star Wars’ world and worked with the Blue Man Group. She showed me I could have a career in art.”

Born and raised in Atlanta, Kaplan says she was the only Black and Jewish girl in her classes. Children would bully her when she mentioned she was Jewish.

Because of that, she says she drew girls with pale skin, blue eyes and straight hair, and tried to hide her Jewishness. She’d straighten her hair and try to enjoy Christmas celebrations at school. There was even a time when she tried going to church.

Only in her mid-teens did she realize that what she was putting on paper was her internalized racism, and so she started drawing people who looked like her and the women in her family.

Upon graduating high school, Kaplan attended the New College of Florida where she studied the intersection of art, religion and politics.

“I was particularly drawn to Emory Douglas, who used art to empower the oppressed and Jean-Michel Basquiat who really changed the way Black artists were perceived in America. He showed that there is not one way to look one way to be beautiful and that there is not one way to look at the oppressed,” she said.

Her thesis piece, “It Is Right To Rebel,” evokes the sentiment of U.S. Sen. Carl Schurz who in 1871 famously said, “My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.”

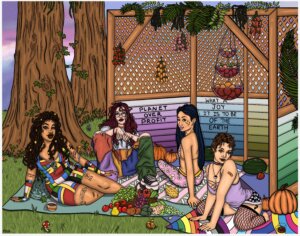

To Kaplan that means pursuing reparations as a form of tikkun olam. In her piece, “Reparations in Pursuit of Repairing the World,” she uses bold colors and a combination of Hebrew and English text to make her point. The words “Justice, Justice You Shall Pursue,” from Deuteronomy 16:20, float above the heads of several women.

“I see reparations as a divine thing, not a political thing. I see it as a spiritual thing. We are still recovering from the trauma of slavery; of economic disenfranchisement and disenfranchisement,” she said.

Kaplan finds endless inspiration from Jewish rituals and holidays.

“Growing up, my mother used to have us explain the Purim story. Over time I began to see both Vashti and Esther as strong women and so I got the idea to show them as two queens of a magical world where women were submissive to no man,” she said.

In “Esther X Vashti,” the two queens appear to rise from the ocean wearing crowns that look like they were crafted from the sun’s rays.

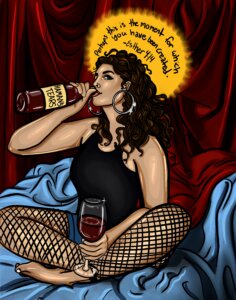

In “Esther,” the queen drinks from a bottle labeled “Haman’s Tears” while wearing a sleek black tank top, denim shorts over fishnet stockings, and sparkling silver hoops. The words “perhaps this is the moment for which you have been created,” from the Book of Esther float above her dark brown hair.

As much as these pieces are meant to inspire and encourage people to act, they are also a means for Kaplan to assert her identity — even as that shadow of shame that came from schoolyard taunts about the impossibility of being Black and Jewish linger.

“Trauma like that at such a young age can damage one’s foundation. I’m still working through it, but now I’m excited to tell people I’m Jewish,” Kaplan said. “Conversations around what a Jewish person looks like are changing. There has been a paradigm shift. There is no one way to be Jewish and all Jews are beautiful.”