He wrote a beloved prayer book. But his gravestone misspelled his name.

Philip Birnbaum, who died in 1988, was a man careful with language, yet a stone of eight words had three errors

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

When the author Philip Birnbaum died in 1988 at the age of 83, he was buried in the Westchester County cemetery of Manhattan’s Jewish Center synagogue. Months later, a monument company installed a headstone that misspelled his name. “Phillip Birnbaum” the stone said, adding an extra “l” to Philip. The stone sat, undisturbed and largely unnoticed, for 34 years.

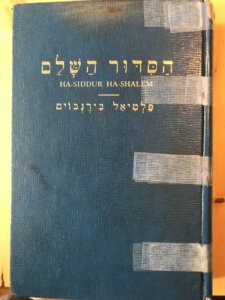

There was a particular sad irony to this single extra letter . Birnbaum was a man who took extreme care with words, a writer, translator, editor and teacher, whose “Ha-Siddur ha-Shalem” — Hebrew for “the full prayer book” — was one of the best-selling Jewish books of the 20th century, widely used in both Orthodox and Conservative congregations.

“I noticed the mistake years ago,” said Lawrence Kobrin, a lawyer and longtime member of the Jewish Center who has warm memories of Birnbaum. “But I didn’t do anything about it. It’s too bad, I thought. But there’s nothing I can do. He left no heirs. And I’m not in charge.”

But when Yosef Lindell, a young lawyer and scholar who was doing research on Birnbaum, found a photo of the headstone on Twitter, he could not believe his eyes. On a tombstone with just eight words, Lindell found three mistakes: Besides the extra “l,” the stone misstated Birnbaum’s birth year as 1905 when in fact it was 1904, and called him a “renouned author and scholar,” misspelling renowned. It also had no Hebrew words, a strange omission for the gravestone of a master Hebraist.

“It wasn’t appropriate to leave it that way,” Lindell told me in an interview from Silver Spring, Maryland, where he lives with his wife and two young sons. “I figured, he was a bachelor, he left no family. No one checked.”

Lindell, a graduate of Yeshiva University, reached out to one of his favorite professors there, Jacob J. Schacter, who had been the rabbi of the Jewish Center during the later years of Birnbaum’s life. Schacter in turn called the synagogue’s current rabbi, Yosie Levine, and Kobrin, the Jewish Center member who had also noticed the errors.

Within weeks, they raised $3,000 to replace the stone with one that not only corrects the mistakes but adds a Hebrew verse adapted from the High Holiday liturgy.

“He instructed the mouths of his nation,” the verse says, “so that they should not err in their language or falter in their speech.”

‘I can still see her lipstick’

I grew up in the Jewish Center and knew Birnbaum, a short, balding man with horn-rimmed glasses and a cherubic face. He occasionally led a class in Pirkei Avot (“Ethics of the Fathers”) on Saturday afternoons, but was otherwise a quiet, friendly and modest presence.

I am also a fan of the Birnbaum siddur. Although I no longer use it on a regular basis, one of my prize possessions is the Birnbaum used by my late mother. Like many of her generation, she would regularly kiss the siddur both before and after she prayed. . On its cover and many of its pages I can still see her lipstick. To me, it is more than just a cosmetic remnant, but a strand of her Jewish DNA.

When Birnbaum died in 1988, I was a reporter at The New York Times and asked my editors if I could write his obituary. Space was always at a premium in those days, and my editors only allowed eight short paragraphs. I called him “the most obscure best-selling author.”

Today, in retrospect, I am happy to find that I got the facts right. I spelled Philip with one “l” and properly said he was born in 1904. I wrote that he came to the United States from his native Poland in 1923, got his doctorate at Dropsie College and served for several years as the principal of a Jewish day school in Delaware before turning his talents to popularizing Jewish knowledge.

The prayer book I’d grown up with was one of 30 tomes that he wrote or translated, including “The Concise Jewish Bible,” “Fluent Hebrew” and “Maimonides’s Code of Law and Ethics.” His books were published by a Lower East Side staple, the Hebrew Publishing Company, which no longer exists.

Birnbaum’s siddur gained wide acceptance because of its accessible language, clear directions and scholarly notes. It was a departure from the formal and stilted prayer books of an earlier generation. “He created an American siddur for the second half of the 20th century from those immigrant and rather embarrassing siddurim,” said professor Jonathan Sarna of Brandeis University.

Today, ArtScroll and Koren prayer books have taken Birnbaum’s place in the pews of Orthodox synagogues. Conservative congregations tend to use more gender-inclusive prayer books published more recently by the movement.

Levine, the current rabbi of the Jewish Center, said that the synagogue still uses Birnbaum books for the High Holidays and festivals like Passover and Sukkot. The volumes are dated, but still popular.

“Like the tefillot and tunes themselves, people get attached to these things,” Levine told me over email. “Holding onto something that’s familiar is comforting. And I suspect the fact that people knew him personally is a contributing factor.”

A ‘lasting memorial’

When Birnbaum died in 1988, Schacter led the funeral. He said he did not remember being involved in the gravestone, which generally is placed up to a year later, but was delighted that Lindell spurred him to correct the mistakes, even after so many years.

The synagogue is planning a dedication ceremony on Oct. 2, the Sunday between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, at the cemetery, Sharon Gardens, in Valhalla, New York.

“A matzevah is a lasting memorial,” Schacter said, using the Hebrew term for the gravestone. “It is the way a person will be remembered. It is crucially important to be absolutely correct as an honor to the person who died.”

Birnbaum was not the only famous Jewish author with an error on his gravestone. When the tombstone for Isaac Bashevis Singer was unveiled in 1992, a year after his death, onlookers were aghast to see that his Nobel Prize was listed as a “Noble” Prize. Singer, like Birnbaum, was born in Poland.

It took five years to correct Singer’s stone at the Beth-El Cemetery in Paramus, New Jersey. At the time, The New York Times quipped: “What writer has not suffered the indignity of a typo?”

Before changing the stone, Kobrin and Lindell, both lawyers, did their due diligence. They looked in court files but could not locate the executor of Birnbaum’s will. They had the name of a nephew in Israel but could not make contact.

“When I first asked the cemetery if I could change the headstone, they said that I didn’t even need permission,” said Lindell, who is 37. “There was no one to ask. But now, if you need to change it, you have to get my permission.”

He let that sink in and added: “And I never even met the man.”