Yes, they’re both Jewish, but Barry Manilow and Lou Reed had something else in common

Two guys from Brooklyn helped to launch Clive Davis and Arista Records into the stratosphere

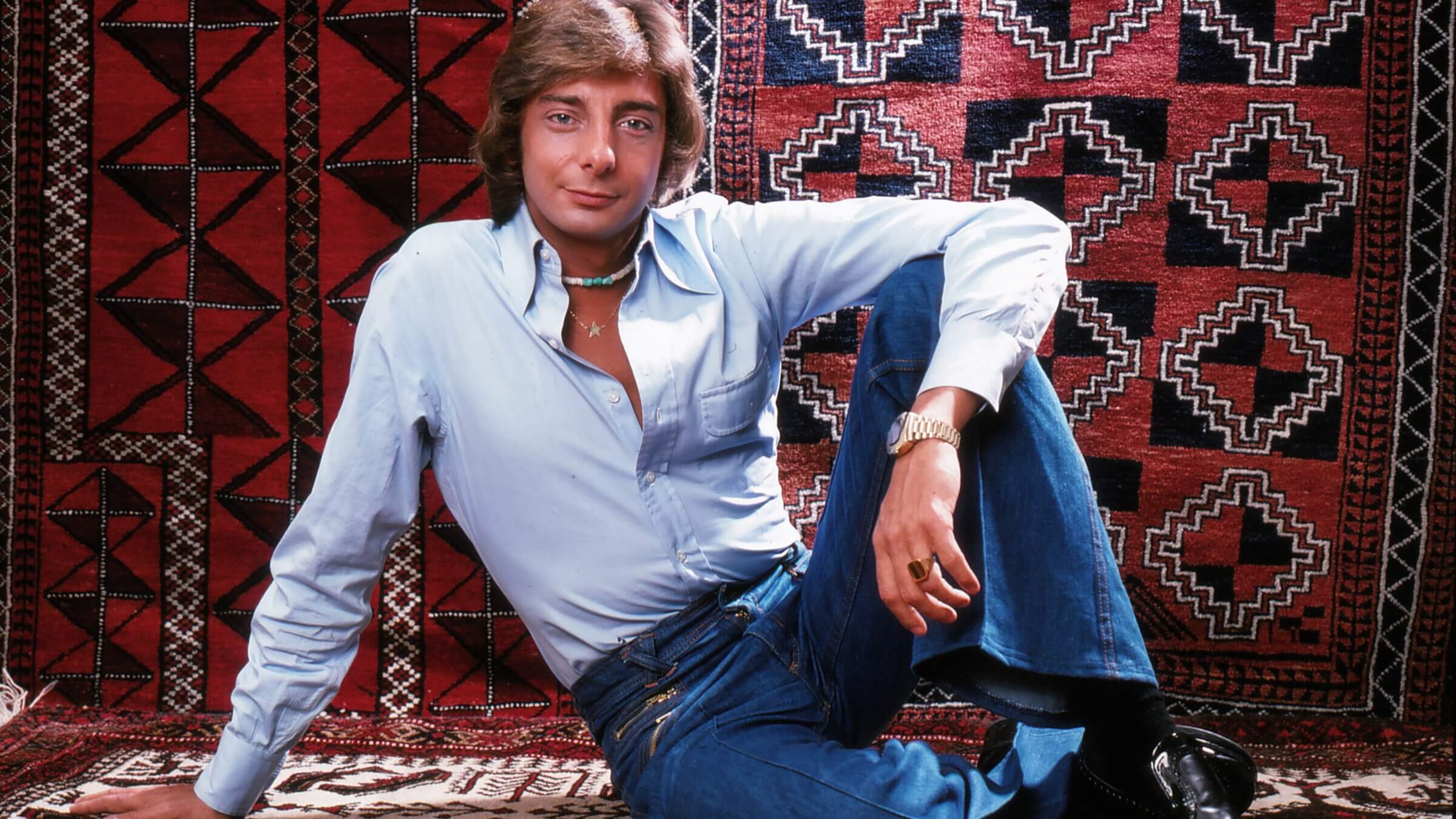

Barry Manilow in New York, circa 1976.

Looking for the Magic: New York City, the ’70s and the Rise of Arista Records

By Mitchell Cohen

Trouser Press Books

204 pages

At first listen — or even the hundredth — Lou Reed and Barry Manilow would seem to be two of the most antithetical musical icons imaginable.

Reed was a gimlet-eyed poet of New York City’s demimonde, whose rapier wit, uncompromising attitude and viscerally powerful music made him a critics’ favorite and inspired several generations of punk and alternative rockers, despite achieving just one Top 20 single (1972’s “Walk on the Wild Side”) over the course of his 55-year musical career.

Manilow, on the other hand, was a writer of commercial jingles who got his big break while backing Bette Midler at the Continental Baths on the Upper West Side. Though reviled by the rock press, Manilow parlayed an affable, unthreatening persona — if you brought him home to meet the family, he’d probably end up playing mahjong with your bubbe — and a flair for Broadway-inspired schmaltz into worldwide sales of over 85 million records.

And yet, as Mitchell Cohen perceptively notes in his new book “Looking for the Magic: New York City, the ’70s and the Rise of Arista Records,” the two singer-songwriters had much more in common than their respective music or images would indicate.

“They were both Jewish, born in Brooklyn,” he writes. “Reed in 1942, Manilow a year later. They’d have heard, as teenagers, music that stirred them, maybe different songs on the same radio stations. Whatever their divergent paths, each spent his early career in versions of the Manhattan underground: Reed in the downtown clubs, Manilow in the baths, playing to clientele that felt like private societies with secrets that the outside world might not comprehend or accept.”

There was one other thing that connected them. For the second half of the 1970s, Manilow and Reed effectively served as the yin and yang of Arista Records, the New York-based independent label founded by Clive Davis. Manilow — who racked up 11 Top 10 singles (including three No. 1 hits) and five Top 10 albums between 1974 and 1980 — gave Arista a steady cash flow, while Reed, whose Arista output included the acclaimed “Street Hassle” and the scabrous concert document “Live: Take No Prisoners” (both released in 1978), lent the label artistic credibility. It was a conceptual balance that, along with a heavy emphasis on New York City-spawned talent, essentially defined the company during its first dozen years, a period in which Davis transformed Arista from a scrappy indie with bubblegum roots into a widely respected commercial force.

Though Arista (which still exists today as a Sony subsidiary) would ultimately achieve its greatest success in the late 1980s and early ’90s via such mainstream-oriented acts as R&B diva Whitney Houston, smooth jazz saxophonist Kenny G, country singer Alan Jackson, R&B/hip-hop trio TLC and the much-maligned lip-syncers Milli Vanilli, Cohen’s book primarily focuses on the early years of the label, when its roster drew heavily from New York’s wide variety of vibrant music scenes.

Cohen, who joined the label in 1977 as a writer of press releases and artist bios before moving to the A&R department (where he remained until 1993), remembers this period with palpable affection. “Working at 6 West 57th in the late ’70s did feel like being part of a New York City cultural renaissance,” he writes. “There was so much going on: no wave, Latin jazz, disco, punk, cabaret. There was a collective feeling that Manhattan was the right place to be, in all its pre-Giuliani seediness and despite its financial travails.”

Not that Clive Davis ever limited his label to local talent. A four-page spread announcing the label’s launch in the Nov. 23, 1974 issue of Billboard featured the disparate likes of Detroit-via-London glam goddess Suzi Quatro, Chicago-born soul legend Lou Rawls, British medieval-prog band Gryphon and southern rockers The Outlaws. But even in that early ad, the presence of such artists as Barry Manilow, Manilow’s friend and fellow singer-songwriter Melissa Manchester, Harlem griot Gil Scott-Heron, folk singer Eric Andersen, jazz hornmen The Brecker Brothers, and Brill Building veterans Tony Orlando and Ron Dante, infused Arista with a heavy Big Apple flavor.

From the beginning, Davis ran Arista like a man with something to prove. Despite a stellar run as president of CBS Records — during which he signed Janis Joplin, Santana, Bruce Springsteen, Chicago, Billy Joel, Aerosmith and Earth Wind & Fire — Davis had been abruptly forced out of the company in 1973 over allegations that he’d misappropriated company funds to pay for his son’s bar mitzvah.

Though his industry stock remained high enough to land him a cushy gig at a rival major label, Davis chose instead to take the reins at Bell Records, a Columbia Pictures-owned indie that had enjoyed considerable success with Top 40 singles but had never been able to crack the more lucrative album market. Davis would change all that, but first he had to give the label a total overhaul, complete with a new name: Arista, a Greek word for “excellence” or “best.”

“Davis’s mandate, he always said, wasn’t to take over Bell Records,” Cohen writes, “but to build a brand-new independent label, a mini-major, ‘from scratch.’ Or at least from scraps. In his new position, he could survey the existing Bell roster and keep whatever intrigued him. The rest would be gone.”

While Bell’s previous president Larry Uttal had operated by outsourcing all A&R duties to a widespread network of U.S.-based indie producers and U.K.-based labels, Davis’ approach was the very definition of “hands-on.”

“Every artist, every record, every choice of a producer would have to have his personal stamp of approval,” writes Cohen.

In building Arista into a company that could go toe-to-toe with the major labels, Davis not only crafted his own redemption story, but also made it possible for several important artists to write redemption stories of their own. Lou Reed, The Kinks, The Grateful Dead and Aretha Franklin all enjoyed commercial and critical comebacks at Arista after losing steam elsewhere, and Davis clearly took as much pride in reviving their careers as he did in being able to flaunt his own success with Arista in the pages of Billboard.

While Cohen was certainly an Arista insider, “Looking for the Magic” is less an industry tell-all than an appreciative flashback to a more freewheeling era of the music business, when an artist like Barry Manilow could land a record deal with a showcase at the Continental Baths — an event where the label execs were the only ones in the audience wearing more than just a towel — or a boundary-pushing poet like Patti Smith (who signed to Arista in 1975) could be considered a top priority at a label that was simultaneously minting money off tartan-clad teenyboppers The Bay City Rollers.

Tales of record company excess are few and far between here (if you’re looking for hookers and mountains of cocaine, this isn’t the book for you), but Cohen does offer interesting insights into the careers and accomplishments of numerous Arista artists, such as Smith, Houston and synth-driven British rockers A Flock of Seagulls.

“Looking for the Magic” doesn’t just revel in the label’s successes, however. There’s a genuine sense of regret when Cohen discusses musicians like Graham Parker, Willie Nile, Dwight Twilley (whose wonderful song of the same name gives the book its title), Heaven 17 and Haircut One Hundred, all of whom should have been much bigger in the U.S., but never fully clicked here despite Arista’s considerable efforts.

At just over 200 pages, “Looking for the Magic” does leave you wanting a little more. Given Cohen’s 16 years with the company, he surely has quite a few more Arista-related anecdotes (and a lot more scandalous dish) in the tank than he offers up here. But as a breezy, humorous and illuminating summer read that vividly imparts the thrills and frustrations of working for a unique label during an unforgettable period of music history, “Looking for the Magic” is pretty hard to beat — and it might even inspire you to give Lou Reed and Barry Manilow some back-to-back spins.