Growing up with a Jewish mom and a famous dad he never knew — the jazz musician Roy Ayers

Nabil Ayers’ memoir reflects on family, identity and his journey to connect with a Black father who was ‘really just DNA’

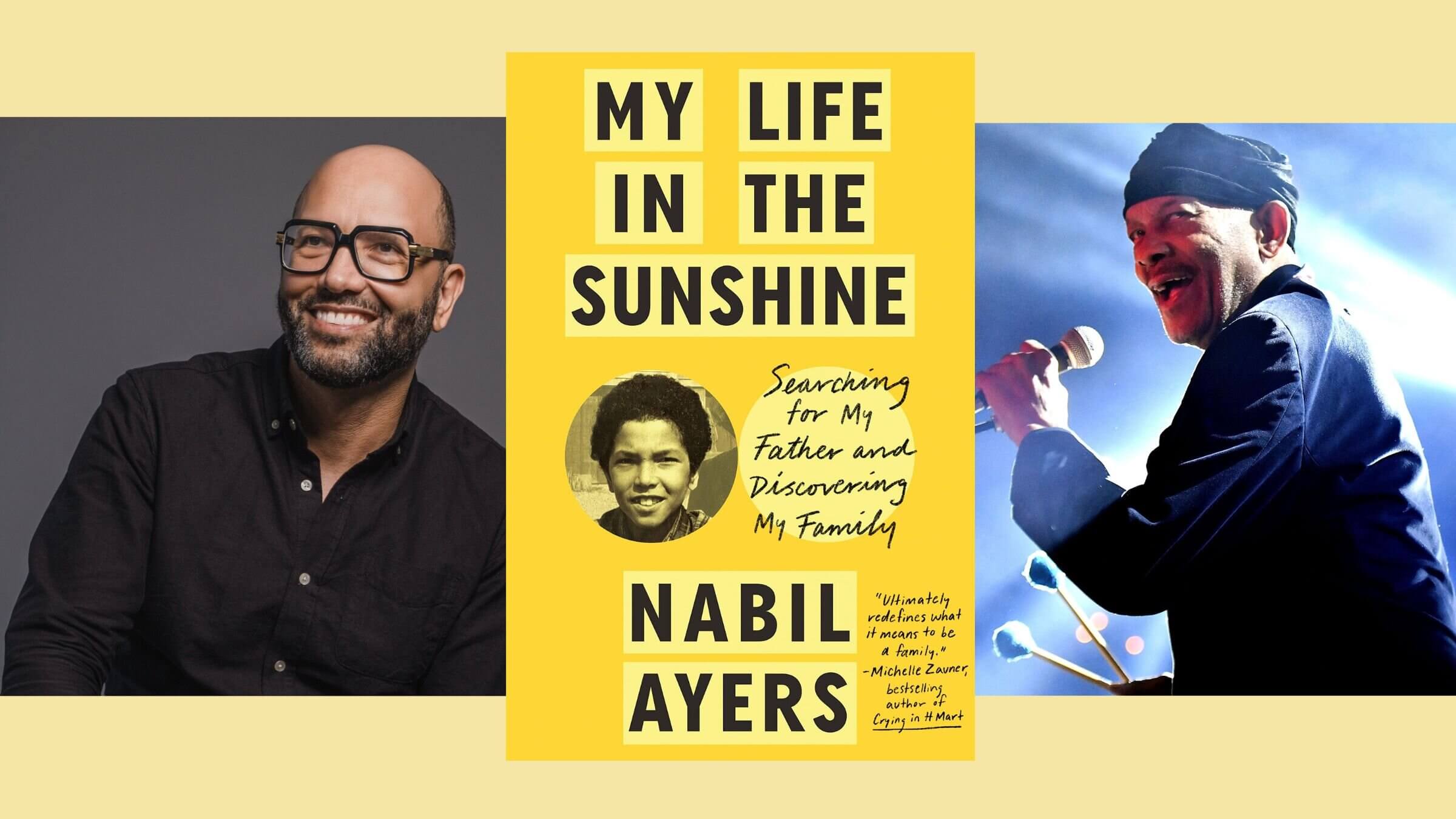

Author Nabil Ayers, left; his father, jazz musician Roy Ayers, right Courtesy of Nabil Ayers (author photo and book cover); and Scott Dudelson/Getty Images (Roy Ayers photo)

Nabil Ayers carries the surname of a famous father he barely knows, except in the ubiquitous music of Roy Ayers – most famously in the 1976 jazz-soul-funk album by that name featuring the hit “Everybody Loves the Sunshine.” For the younger Ayers, it pops up to surprise him when he least expects it.

Flashback to 1970, when Louise Braufman, a white Jewish former ballerina working as a waitress in New York took one look at the rising African American jazz composer and vibraphonist and thought she’d have a baby with him.

After a few casual dates, she asked Roy Ayers and he agreed, cautioning her that his career was his priority, and he wasn’t available for a serious relationship or any form of parenting.

Nabil Ayers was born of that union and grew up with a strong sense of self, despite his father’s absence. His new memoir, “My Life in the Sunshine: Searching for My Father and Discovering My Family,” explores his unconventional but richly diverse childhood, his own rise in the music industry and the search to connect with his father, which led to discovering paternal Black half-siblings and an enslaved ancestor.

Generations of Jewish ancestors

“Writing the book made me think about my identity and process it,” Ayers said. “I still don’t really identify as any race. There’s my mother who raised me and my father who was really just DNA, and there’s all the people who helped raise me. I felt like everybody contributed to my identity. How can I choose just one? And that absolutely includes the three generations of Jewish ancestors who are a huge part of that.”

The book title is from the opening lyrics of Ayers’ father’s signature hit, “Everybody Loves the Sunshine,” which was moderately successful when it came out in 1976. Recorded at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in New York City, the song has since become a cultural touchstone with a blend of soul, funk, jazz, rock and electronic music that blends genres with cross-generational appeal.

And true to the name of the album featuring it, the song is everywhere. It’s been sampled more than 100 times by an array of artists from Mary J. Blige, Common and Tupac, to J. Cole, Snoop Dogg, Pharrell Williams and the Black Eyed Peas, and covered by D’Angelo and Cibo Matto. It’s also been used in commercials and movie soundtracks. “I’ve heard it in many different iterations over the years, a perennial, persistent reminder of my otherwise absent father,” Ayers writes.

Thanks to his mother, Ayers didn’t grow up feeling the lack of his father’s presence. Her brother, jazz saxophonist Alan Braufman, was a strong, steadfast influence. “Every important paternal moment was with him,” he said.

Culture more than color

He grew up with a solid sense of self in diverse communities in Greenwich Village, Brooklyn, Boston and Amherst, Massachusetts. When his mother attended the University of Massachusetts, they lived in family housing with families of different races, multi-ethnic and multi-racial kids and single parents. Culture was emphasized more than color, he said.

Ayers’ Jewish identity came from family rather than religious institutions. During visits to his mother’s parents, who were Romanian and Russian Jews, and his grandmother’s father and his wife in Flatbush, Ayers enjoyed eating gefilte fish, learning Yiddish, and celebrating the holidays. (Interestingly, long before he met Braufman, a young Roy Ayers played with Herbie Mann, who hailed from similar ancestry.)

“I have incredible memories of all these Jewish Brooklyn experiences as a mixed-race hippie kid who felt very connected to it, not so much in a religious way but very much in a cultural way, really loving and respecting it. I felt very cool, and proud, like I belonged to something interesting as a kid.”

His mother and uncle were drawn to the Baha’i faith which emphasized peace and equality. “My exposure to Baha’i and Judaism was about good people and great food, things that kids like,” Ayers said.

When he was 10, his mother moved them to Salt Lake City, the mostly Mormon city where he stood out as different. While some kids asked where he was from, whether he was adopted, and wanted to touch his Afro, Ayers said his sense of identity was intact from having not been “the weird kid for the first 10 years of my life.” He recalls a synagogue and JCC in Salt Lake City and feeling a connection with some of the Jewish students in his school.

Musical ambitions

Ayers longed to play music from an early age. But as a biracial boy, he couldn’t fully identify with the appearances of white or Black stars like the Beatles and Stevie Wonder. Then, at age 5, he discovered the hard rock band Kiss. The heavy makeup they wore obscured their features, enabling him to imagine new possibilities. “I found something attainable in Kiss,” he writes. “I had no idea what they looked like in real life and for that reason, I felt there was nothing that stopped me from looking like them.” Learning that Kiss members Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley “were two Jewish guys from New York, strengthened my sense of solidarity with them,” he said.

Music remained a constant throughline in his life, courtesy of his father’s genes, his mother’s dance background and his Uncle Alan’s encouragement. He attended many concerts as a young boy, sometimes seeing his father perform, which stoked his young ambitions. Ayers played drums in bands with friends from third grade through high school, expanding his musical repertoire and tastes along the way.

As a rite of passage when graduating high school, Ayers’ mother suggested that he might want to change his surname from Braufman to something easier to spell and pronounce. He agreed, becoming Nabil Ayers as he prepared to attend college at the University of Pacific Sound in Tacoma, Washington.

It wasn’t his first name change.

While his mother was in the hospital after giving birth, her father had the middle name Sol put on Nabil’s birth certificate. “Once my mother got home, she changed my middle name to Ahmal after an opera she saw,” Ayers said. “I could have been Nabil Sol Braufman my entire life.”

A career of his own

Music continued to shape his identity and career. As a drummer, Ayers performed in several bands including The Long Winters and Tommy Stinson. On his own record label, The Control Group/Valley of Search, Ayers has released music by Cate Le Bon, Lykke Li, The Killers, PJ Harvey, Patricia Brennan, and his uncle, jazz musician Alan Braufman. He co-founded Seattle’s famed indie rock Sonic Boom Records store, which was sold in 2016. Today, he is the president of Beggars Group US, where he oversees the creative, marketing, radio, sales and other components of releasing albums for The National, Big Thief, Grimes, Future Islands and St. Vincent, as well as the reissue of albums including the Pixies’ “Doolittle,” which was certified platinum in 2019.

As an adult, Ayers finally connected with his father and learned the names of three half-siblings. Through contact with them and DNA testing, he became aware of more ancestors on his father’s side, including a great-great-great grandfather, Isaac Ayers, who was born into slavery and owned by a man named Dr. Ayers of Ashland, Mississippi.

As the missing parts of his paternal identity became clearer, Ayers found that being biracial impacted his attempts at dating. Online dating site apps required him to specify the kind of women he wanted to meet. “You can choose races that you like or don’t like, which I had a hard time with,” he said. Friends introduced him to women, most of whom were white. “I quickly found that dating was bringing issues of race to the forefront in my life, in a way few other moments had,” he writes.

A Jewish wedding

While attending a colleague’s wedding, Ayers met a woman named AJ. “I thought maybe she was kind of Italian,” he said. He introduced himself and they began dating. He overheard her talking to a relative on the phone who asked if Nabil was Jewish. She responded that he wasn’t. When he later explained his Jewish background, she shared hers, deepening their bond.

They were married in Hollywood four years ago in a Jewish wedding with a female rabbi. AJ’s parents walked her down the aisle to violin music from “Fiddler on the Roof,” while Ayer’s mother and her husband Jim walked him down the aisle to “Everybody Loves the Sunshine.”

“We did everything: chuppah, I stomped on a glass, and we were lifted in chairs to ‘Hava Nagila,’” he said. “It felt very powerful, very connected.”

Ayers and AJ meet with family for many holidays. Lighting their menorah reminds him of his great-grandparents. “It’s tradition – doing something that has the same food, the same prayers, reminds me of a time in my life 40 or 50 years ago,” he said.

While writing hasn’t replaced music in Ayers’ life, writing about race and music for The New York Times, NPR, Pitchfork, Rolling Stone and GQ “is my new artistic thing.” As he tours with his memoir – which has received praise from Oprah and Black Jewish actor Daveed Diggs – he continues to expand his sense of self and family on both sides. “I’ve had so many great influences and parts of my life and my Jewish ancestors have been a huge, important, memorable part of that,” he said.