Meet the musicians turning old Yiddish poems into 21st-century songs

Two new albums reimagine a centuries-old tradition of adapting poetry to music

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

To her early 20th-century audience, Tsilye Dropkin’s Yiddish poetry was as shocking for its content as its form. A Russian-born poet who immigrated to New York City at the age of 25, Dropkin broke away from the traditional poetic formats of her Jewish predecessors, opting for the free verse experimentation that was gaining steam in the greater literary world. And rather than portraying broad themes like the political struggles of her people, as was de rigueur in Yiddish poetry at the time, Dropkin favored highly personal subject matter.

Love and sex, eros and thanatos, intense longing and raw flesh — this was Dropkin’s poetic domain. And as such, she was mostly ignored or criticized by the (mostly male) Yiddish literary establishment.

But time has caught up with Dropkin. Yiddishists study her in universities around the world. Her work is available in translation for those looking to connect with this revolutionary woman writer. And her poems have also drawn the attention of Yiddish musical artists, who find in her work themes and imagery of remarkable contemporary resonance.

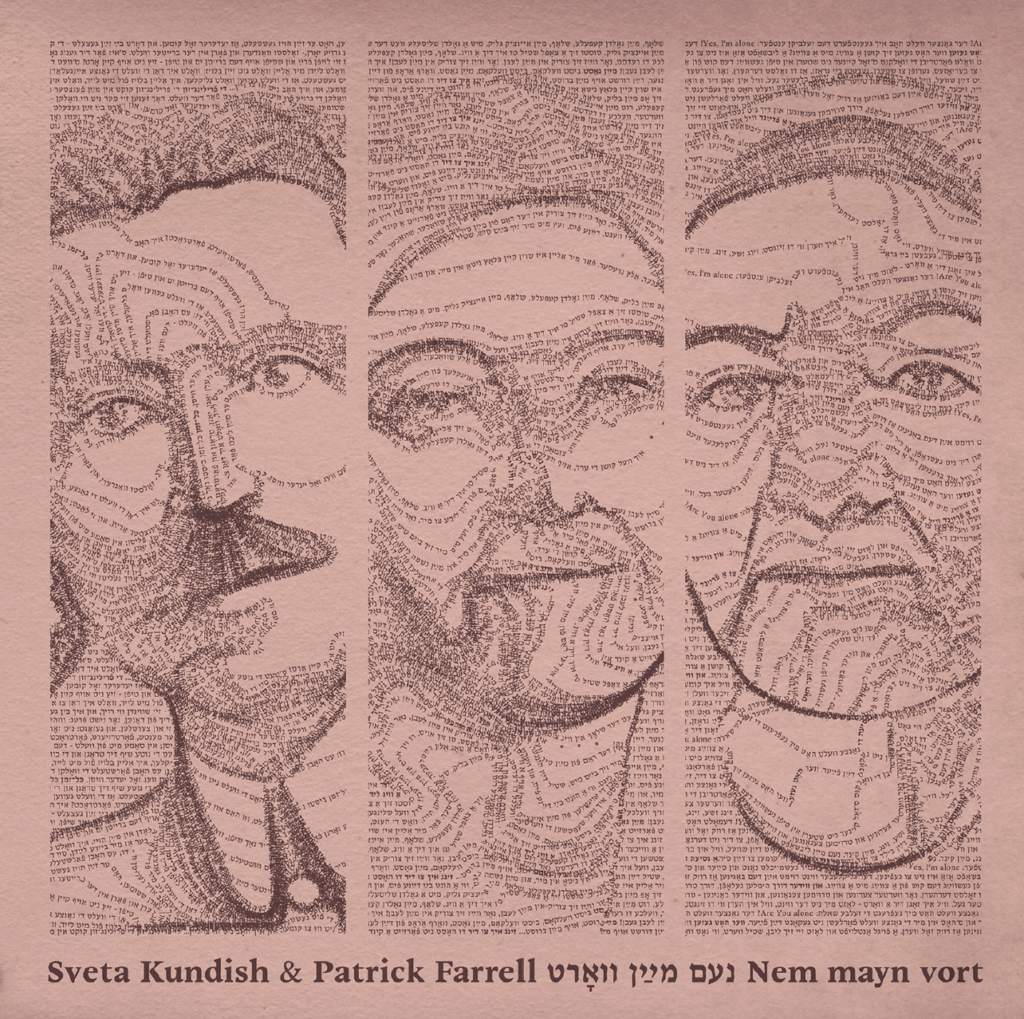

Two new Yiddish music albums place Dropkin’s work, along with that of other 20th-century Yiddish poets, into 21st-century musical settings, illuminating an oft-overlooked body of work for contemporary listeners. While “Nem mayn vort,” by Sveta Kundish and Patrick Farrell, and “Kosmopolitn,” by the duo Tsvey Brider, boast different styles, they share at least one similarity: a mission to celebrate this rich literary tradition through music.

Both albums are text-driven. That is not unprecedented: Yiddish singers have adapted poetry into song for over a century. But those efforts were often folk-based, resulting in songs that can be (and are) sung by everyone during school events, concert singalongs and other Yiddish gatherings. But these arrangements are designed for performance. A listener is not likely to walk away humming these tunes; rather, these recordings feature vocalists of startling character and range, interpreting and delivering the source poetry in highly personal and idiosyncratic musical vessels. These are art songs, not folk songs.

Tsvey Brider’s album leads off with a version of Dropkin’s “Tsirkus Dame,” known more commonly as “The Acrobat.”

In the album’s liner notes, singer Anthony Mordechai Zvi Russell, 42, explains the modern resonances that drew him to this poem. “This circus lady felt like someone who could have been in the Bay Area, where I had lived for so long,” Russell wrote. “I can imagine her telling someone that she’s attracted to knives, and they’d just shrug their shoulders like it’s totally normal and say, ‘That’s cool. Love is love.’”

Tsvey Brider, a duo that formed in 2017, includes Russell and the pianist and accordionist Dmitri Gaskin, 26. “Kosmopolitn,” augmented by the Bay Area klezmer trio Baymele (of which Gaskin is also a member), features Yiddish poems in romantic, chamber-music-like settings that draw variously upon cabaret, operetta, theater music, Yiddish chanson and klezmer. The result is an atmosphere of all-encompassing, cosmopolitan “café” music — hence the album’s title.

This melange of genres is perhaps most apparent in “Mayn heym” (“My Home”), based on a poem by Avrom Reyzen. The piece opens with a free-metered accordion solo before ramping up with a playful, vaudevillian strut powered by piano. Bay Area early-klezmer outfit Veretski Pass provides a gorgeous instrumental section. Russell’s dramatic vocals — he is a trained opera singer with a resounding bass — underline what he sees as the sarcasm beneath an ostensibly nostalgic elegy for life in the shtetl.

“My whole idea of this poem is that it’s a little ironic,” says Russell.

Perhaps appropriately, one of the album’s most modern pieces is “Shikago (Chicago),” a poem by Ben Sholom (who immigrated to that city from Vilna in 1909) with music composed by Veretski Pass’s Joshua Horowitz. The arrangement deconstructs an old folk melody and adds a smattering of urban sounds — pounding pianos, screechy violins — with nods to jazz and blues. The effect is that of a greenhorn experiencing a Midwestern industrial city for the first time.

Sveta Kundish and Patrick Farrell’s “Nem mayn vort” opens with “A Journey,” one of four songs on the album based on poems by Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim. Born in Lithuania, Ben-Hayim survived the Holocaust and immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1947, where she lived and taught at a kibbutz for many years, writing Yiddish poetry to this day. Interpreted by Kundish and Farrell, the opening number pays tribute to this stark history: Kundish makes use of her soaring soprano to sing the first verse a cappella, before Farrell enters with a musical rejoinder, based loosely on the melody and played on solo accordion.

“The whole world asked me the same question — Are you alone?” the song asks. The reply is ruthless: “Yes, I’m alone.” Kundish renders this refrain — ”Are you alone? Yes, I’m alone” — in English, emphasizing the poet’s alienation. The music remains calm until the final verse, when the narrator sees the image of her unnamed beloved smiling. “Within me the whole world could not douse your fire,” Kundish sings in a hot frenzy, concluding the song with wordless vocals that soar over Farrell’s fiery accordion ostinato.

In an email interview, Kundish, 40, said that the duo’s desire to embrace a new challenge and bring attention to marginalized Yiddish poetry spurred them to record “Nem vayn vort.” “We are constantly on the lookout for new poetry which moves us and may inspire new songs,” she said. “We specifically want to highlight women Yiddish poets, who we feel, in general, don’t get the attention and accolades they perhaps deserve.”

Farrell’s accordion grounds the musical settings, lending the project the flavor of Central European chamber music, albeit filtered through a very contemporary sensibility. Kundish said that the duo’s omnivorous musical taste prepared them to record this album. “We’ve both studied and feel at home in many different musical styles, from classical music to jazz to theater to Balkan folk music to khazones to improvisational music to, of course, klezmer and Yiddish song,” Kundish said. “We try to bring all these influences and all our knowledge together when creating original music.”

Farrell, 44, said the album’s concluding number, “Di frilingzun” (“The Spring Sun”) embodies this approach. The duo took the text from a poem by Avrom Reyzen, a Forverts contributor and contemporary of Y.L. Peretz and Sholem Asch.

“We were drawn first to the text for its message of hope and renewal, its clear meter and rhyme, and Reyzen’s simple but profound language,” Farrell said. In a free improvisation section on the accordion, he lays down extended, modern jazz chords. Kundish, a trained cantor, sings a prayer-like melody that slowly transforms into an art song. The number concludes with a joyfully anthemic nigun.

Russell came to Yiddish poetry via the stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Bashevis’ city dwellers, whom he describes as “a collection of idiosyncratic, cultivated, eccentric and occasionally licentious individuals,” demonstrated to him the remarkably modern nature of this body of work. “I feel an affinity with them and with the real-life cultural milieus that created the poetry,” he said.

Russell explains how this plays itself out in Tsvey Brider’s rendition of Melech Khelmnitsky’s poem “Sheyne fremde froy” (“Winsome Wondrous Woman”). The poem is set in a cafe, one of the few contemporary public spaces where men and women mixed freely. In concert, Russell tries to recreate that dynamic. “Often, when I perform this song live, I’ll spring off the stage into the audience to dance with a succession of lovely, willing partners,” Russell said. Quoting himself, he added, “After all, we’re merely playing our parts as idiosyncratic, cultivated, eccentric and occasionally licentious individuals.”

Which is exactly why these two albums that revive century-old Yiddish poetry speak with urgent fluency to current listeners.