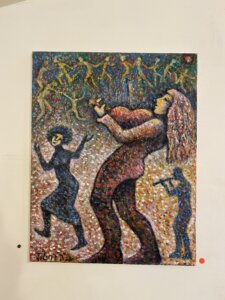

How a Holocaust survivor from Slovakia became a modern-day Chagall

93-year-old Tibor Spitz found a second (or maybe a third) life as an artist

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I first met Tibor Spitz at the opening of his retrospective at the Unison Arts and Learning Center in New Paltz, New York, in late August. Helene Bigley, a co-founder of the center, who had been my pandemic walking partner during all those difficult months, insisted I meet him. The gallery had reopened and this would be a celebration, she said.

But when she told me that Spitz was a Holocaust survivor from Slovakia, I resisted.

Over the years, as second generation, I’ve written a lot about the Holocaust, my own family’s story, in particular, and done what Helen Epstein in her book, “Children of the Holocaust,” calls the “emotion work” for the family. As Epstein writes, many of the survivors kept their stories hidden from their children and from themselves.

When the second generation began to ask questions, and were met with silence or denial, the family dynamics often shifted. Mine certainly did. Once I found out the truth about my murdered relatives, particularly my maternal grandmother, Nanette, who was killed at Auschwitz when she was in her 50s, I became enraged.

I read and wrote nonstop for many years about the Holocaust, or the Holocaust surfaced in my work unexpectedly as I was writing about other things. I felt it was my mandate, as a writer, to bear witness and document the genocide in a way my parents could not. Eventually, after a lot of writing and therapy, my rage eased and I became interested in international peacemaking, truth and reconciliation, conflict resolution and human rights initiatives.

Now older, I am protective of my equilibrium and do not read or write much about the Holocaust anymore, though, oddly, I enjoy German films and contemporary German authors, such as Jenny Erpenbeck, in which there is a reckoning with the fascist and communist past. (She is East German).

It’s not that the killing fields have faded from memory, only that I can manage the specter of the atrocities and my personal losses if I remain somewhat distanced and self-protective.

I told my friend I wouldn’t come to Spitz’s opening, but when I looked him up online, and saw his paintings, my curiosity was piqued. If Chagall had been a pointillist, he would have painted like Tibor Spitz. His canvases and ceramics are masterpieces. I write about art and artists a lot. Why had I never heard of him before?

The room was crowded, just about everyone unmasked, except for me and one or two others. Bigley spotted me and dragged me over to meet Spitz, a short, muscular 93-year-old who reminded me both of Picasso and my Austrian-born father.

Spitz pointed at my mask aggressively.“Why are you hiding behind that?” he said and pulled me towards him in a big bear hug.

Hiding. It was the perfect description of my mood.

I decided to leave, only to return a few days later when Spitz and his wife Noemi, also a Holocaust survivor, were doing a “gallery sit” and he told his survival story.

He said that he and his family had lived for seven months underground in a forest dugout, no more than a mound of reinforced earth, overlooking Dolný Kubín, a mountainous region of northern Slovakia, near the Polish border. They subsisted largely on frozen berries and edible roots, dodging Nazi police patrols.

Although he didn’t become an artist until he retired as a chemical engineer for IBM in 1968, he’d always wanted to be one, and repeated and stored the mystical stories his cantor father told him when he was a boy, even more so when they were in hiding.

“If I hadn’t been able to imagine something else, I would have gone insane,” he said.

This time, the gallery was not crowded. I stood back, notebook in hand, and listened to Spitz talking to a woman about a ceramic image of horses she was interested in buying.

“To help people feel good is the only thing worth doing,” he said. “Horses are serene creatures and they are vegetarian.”

That gave me pause. He seemed neither bitter, nor enraged; he had found happiness in his work. I want to get to that peaceful place as I age, I thought.

After everyone in the gallery had left, there was still some time before closing, so I suggested to Spitz and his wife that we sit in a circle a bit distanced so I could take off my mask. One of my hearing aids failed, and Noemi offered to put in a new battery, then instructed me on prolonging its life.

It was now a family gathering.

We sat alone, surrounded by Spitz’s powerful work talking about painting and writing, exercise and the redemptive power of making art. Spitz’s work exudes more strength than pain, even a bit of whimsy at times. And the ceramics, in their two dimensionality, bring the faces and bodies from his memory and imagination to eternal life.

“Tibor Spitz: A Retrospective: Stories, Remembrances,”” curated by Simon Draper and Faheem Haider, at the Unison Art Gallery in New Paltz, New York, will run through Sept. 18. A PBS documentary about Spitz and other Holocaust survivors can be viewed here: www.pbs.org/show/we-remember-songs-survivors.