Leonard Cohen’s lost novel shows the artist’s surprisingly vulgar and violent side

The songwriter wrote the novel ‘A Ballet of Lepers’ in his early 20s, but didn’t publish it in his lifetime

Leonard Cohen in 1968. Photo by Getty Images

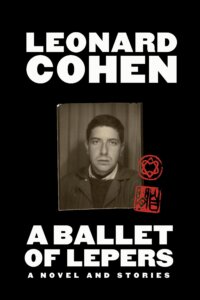

A Ballet of Lepers: A Novel and Stories

By Leonard Cohen

Grove Press, 256 pages, $25

Leonard Cohen’s extensive body of work includes over a dozen albums, several collections of poetry, and even some fiction from the early years when he thought he might have a literary, rather than musical, career. But his first novel, “A Ballet of Lepers,” was never published during his lifetime. For decades, Cohen’s four drafts lay buried in his archives at the University of Toronto; now, editor Alexandra Pleshoyano has combined them with several short stories in a collection of the artist’s earliest, unpublished work.

As its somewhat macabre title might suggest, “A Ballet of Lepers” is not light reading. In fact, it’s so physically and emotionally brutal that after finishing it, I had to put my copy away for a week. But it’s also an astonishingly deft and confident work of juvenilia that prefigures the themes that would propel Cohen to fame and preoccupy him throughout his life: passion and violence, sacredness and shame.

Set in post-World War II Montreal, the novel focuses on an unnamed 35-year-old man stuck in a dead-end bookkeeping job and, by his own account, suffocated by his overbearing lover, Marilyn. In the opening scene, the narrator learns that his grandfather, whom he believed to be dead, is in fact alive and coming to live with him. Arriving at the train station to pick him up, the narrator sees this long-lost relative beat up a police officer who has chastised him for spitting in the wrong place. This incident is the narrator’s first glimpse into his elder’s unapologetically aggressive demeanor, which only escalates from there: Within hours of arriving at his grandson’s rooming house, he angers the landlady by breaking a window for better airflow.

From his grandfather, the narrator learns how shockingly and seductively easy it is to behave violently and get away with it. This new philosophy animates a life that had seemed leaden and aimless. Instead of simply tolerating Marilyn, the narrator deceives her into thinking he wants to get married and then jilts her in a humiliating manner. Instead of going through the motions at his job, he plays a series of cruel psychological pranks on a credulous coworker. Most importantly, he begins to stalk and torment Cagely, a train station employee whom he first saw when collecting his grandfather, and whom he hates simply because he is ugly.

The narrator delights in the process of manipulating and hurting those around him. But he faces a harsh reality check when it’s revealed that the “grandfather” he’s been caring for is not actually related to him at all, and that their bond is the result of a clerical error. While the narrator has come to see the old man’s behavior as a kind of philosophical inheritance, he now realizes that living with this violent man has simply brought his most repulsive impulses to the surface. “Was I attributing to him some influence which he had never had?” the narrator wonders. “Wasn’t violence taught eloquently enough in this city, in the forest, in the changing sky?”

Cohen wrote “A Ballet of Lepers” between 1956 and 1957, likely after dropping out of law school and returning to his childhood home in Montreal. (Ironically, he lived there with his own grandfather, a gentle Talmudic scholar who was by all accounts as different from the novel’s patriarch as possible.) One of Cohen’s earliest works, the novel is raw and forceful in describing the slippery nature of desire. Few people go around breaking windows at will, but most have confronted impulses that contravene social norms or, worse, personal principle.

“A Ballet of Lepers” does stumble in its chauvinistic attitude towards its female characters: Marilyn, the landlady, and Cagely’s venal wife, who willingly assists in his humiliation. Unburdened by their own motivations or desires and content to help the narrator through his existential crisis, all three read more like plot devices than fully realized characters. The narrator and the old man inflict extraordinary violence on all three, and because of Cohen’s lack of attention to them, it’s hard to excuse that as gritty storytelling or philosophical allegory. To a charitable reader, these three characters might testify to a kind of callousness common in young writers. To an uncharitable one, they demonstrate a fascination with the abuse of women.

At the end of the novel, the narrator decides to bring some soup to his landlady, whom his not-grandfather has beaten in a climactic scene. But the moment feels less like a gesture of generosity or genuine recognition of the woman’s needs than a performance of growing up. Cohen’s narrator learns the bitter consequences of cruelty, but he never learns to see women as anything other than vehicles for his own self-expression.