The saga of Hollywood’s most terrifying vampire (and his Jewish parents)

1972’s ‘Blacula’ was the brainchild of a couple of Jewish movie buffs from New York City

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The playground debate still rings vividly in my ears.

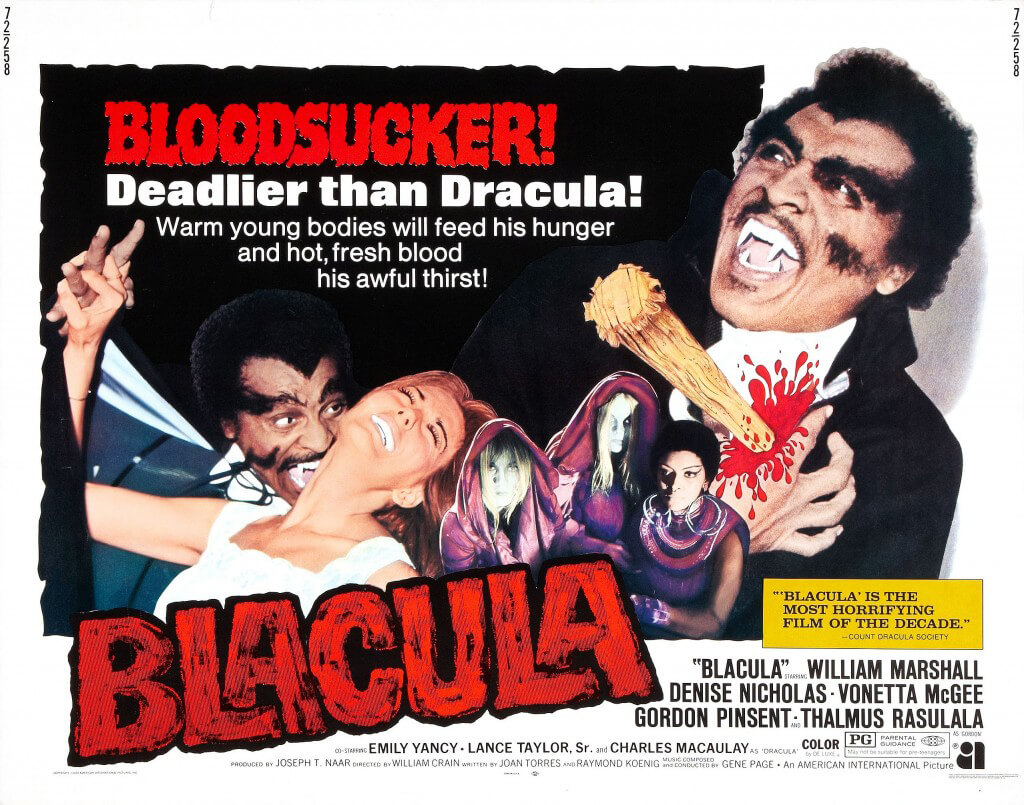

I’d seen an ad in our local paper for a film called “Blacula,” which promised a titular character “Deadlier than Dracula!” As a budding fan of horror movies, this concept thrilled me to no end; but when I told my fellow second graders about it at school the next day, the film’s tagline triggered more questions than excitement.

“How could you be deadlier than Dracula?” my friend Peter wanted to know. “Dracula can already kill you pretty easily.”

“I don’t know — maybe Blacula can kill you quicker,” I replied.

“Or maybe Blacula has killed more people than Dracula,” suggested our pal Andrew.

“No way,” Peter insisted. “I’ll bet you anything that Dracula has killed way more people than Blacula.”

This intense theoretical discussion went round and round until the school bell rang, without us coming to any sort of consensus on the matter. The one thing my pals and I could all agree upon, however, was that the idea of a Black Dracula was really, really cool.

We weren’t the only ones who thought so.

Released in the summer of 1972 by American International Pictures, an independent studio best known for low-budget horror and teen-oriented films, and helmed by Black director William Crain, “Blacula” became one of the year’s highest grossers. The critical reception was profoundly mixed — Gene Siskel called the film “well-made and quite frightening,” while Rex Reed described it as “the worst Black film ever made” — but audiences responded positively to William Marshall’s imposing turn as a vampire who wreaks havoc upon 1970s Los Angeles.

“Blacula” also provided a big break to soul trio The Hues Corporation, which appeared in the film and recorded three songs for its soundtrack, which also featured a wonderfully funky score by Gene Page. Two years later, they would top the Billboard Hot 100 with “Rock the Boat.”

The movie was the first serious Hollywood horror film to feature a predominantly Black cast. Though Reed hoped it would mark “the end of Black exploitation trash forever,” any horror buff worth their wolfsbane can tell you that it not only inspired a number of other Afrocentric fright flicks in its immediate wake (including the 1973 sequel “Scream Blacula Scream”) — it’s also commonly cited today as a groundbreaking work whose bloodline (pardon the pun) extends all the way up to Jordan Peele’s acclaimed horror films like “Get Out” and “Nope.” But what most horror fans still don’t know, even 50 years after the film’s original release, is that Blacula’s parents were Jewish.

How Dracula became Blacula

The original idea and eventual script for “Blacula” were created by Joan Torres and Raymond Koenig, two Jewish movie buffs from New York City. (Torres, nee Harris, is the great-granddaughter of Yiddish poet Morris Rosenfeld, whose work — most notably “Requiem,” his poem for the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire — regularly appeared in the Forward during the early 20th century.)

After relocating to Los Angeles in the late 1960s, the two friends regularly attended screenings at the Fox Venice Theater, a second-run movie house on Lincoln Boulevard. Torres and Koenig noticed that horror films did exceptionally well at the Fox Venice, especially among the neighborhood’s Black residents.

“Whenever a horror film was playing,” Torres recalled, “the place was packed with African American families who would scream and laugh and have a rollicking good time.”

Torres, a successful educational screenwriter, had thus far made little headway in her attempts to break into the world of Hollywood screenwriting. But when her brother, author and playwright Andrew B. Harris, noticed an ad in Variety calling for horror scripts, he advised her to try writing for that particular genre.

Not a big horror fan herself, Torres initially resisted the idea until she and Koenig saw a preview for “Shaft,” a new action film directed by Gordon Parks. Though it wasn’t a horror flick, “Shaft” was a major studio project aimed at a Black audience, a fact which got Torres’ and Koenig’s wheels turning.

“From all those nights at the Fox Venice, Ray and I knew that there was a Black audience waiting for something fun and scary,” Torres said. “Yet there had never been a horror film with a Black cast. Maybe we could write one!”

A classic horror “monster” seemed like the best place to start, but which one would they pick? “The vampire idea took off pretty quickly, because of the potential that was there for a love story,” Torres said. “Up until then, though, vampires had always been villains. I’d gone to UC Berkeley right around the time that all hell was breaking loose with the anti-war demonstrations, civil rights, the Black Panthers, and everything else, and so I wanted our Black vampire to have a noble cause.”

Torres and Koenig came up with the idea of an 18th-century African prince named Mamuwalde, who had come to Europe in hope of convincing the continent’s rich and powerful to end the African slave trade. Unfortunately, one of the noblemen he lobbies turns out to be Count Dracula himself; enraged by Mamuwalde’s proposal, the Count turns him into a vampire and condemns him to crave blood for all eternity.

Two hundred years later, his coffin turns up in LA, where a pair of gay antique dealers — delighted by the campy idea of transforming the coffin into a guest bed — inadvertently unleash the undead prince upon South Central Los Angeles, where Mamuwalde encounters the woman he believes to be the reincarnation of his dead wife, Luva. Torres wanted to call the film “Black Dracula,” but Koenig had an even better idea: “Blacula.”

Joe Naar, the producer who optioned the script, later admitted to the writers that, though he hated scary movies, he bought this one because “it was the best single word title I’d ever seen.”

Not a ‘Blaxploitation’ film

While “Blacula” is typically considered a “Blaxploitation” film, Torres takes issue with the classification.

“I always thought of it as just a vampire picture with a Black cast,” she said. “I wasn’t making heroes out of pimps and drug dealers, which is what I thought of as exploitation. My motives were to create a fun film for the audience I’d seen so many pictures with at the Fox Venice.”

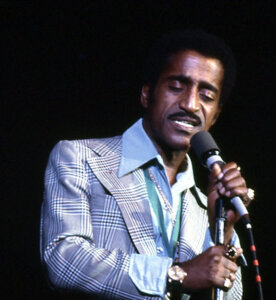

In an effort to make the film’s characters believable to their audience, Torres and Koenig hired their friend Wallace Sides, a Black artist and illustrator from South Central LA, to help with the dialogue. Sides also drew a striking pen-and-ink cover for the script, which featured vampiric images of three actors that Torres and Koenig thought might be right for the Mamuwalde role: Max Julien, Raymond St. Jacques and Sammy Davis Jr. — the latter of whom would have given “Blacula” even more of a Jewish pedigree.

In the end, however, AIP went with William Marshall, an acclaimed stage and screen actor whose regal bearing, towering frame and stentorian voice perfectly suited him for the part of the undead African prince.

Though much of “Blacula” plays out as Torres and Koenig intended, the pair were unhappy with AIP’s last-minute changes to the finale. Originally written as a romantic scene between Mamuwalde and Tina/Luva (played by the luminous Vonetta McGee), the film’s conclusion was completely revised to make Mamuwalde and his vampire minions lay waste to a considerable chunk of the LAPD. (“AIP decided Black people wanted to see cops getting killed,” Torres ruefully recalls.) Torres and Koenig found the experience of working on “Scream Blacula Scream” even more frustrating, and the pair’s screenwriting partnership ended shortly thereafter.

Life after ‘Blacula’

Torres, who now lives in New Mexico, has since achieved success in far more dignified writing fields (her many credits include co-writing the 1986 nonfiction bestseller “Men Who Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them” with Dr. Susan Forward, and translating and adapting the work of Polish playwright Janusz Glowacki’s work for the American stage). Yet she still clearly delights in the thought of being, as she puts it, “Blacula’s Yiddishe Mama.”

But when asked about the painfully obvious Black-oriented horror knock-offs that sprang up afterwards — a trend later spoofed by “The Simpsons” via such nonexistent titles as “Blacula vs. Black Dracula” and “The Blunchblack of Blotre Blame” — she just chuckles at the memory.

“Well, AIP asked Ray and I to write ‘Blackenstein,’” she said. “I told them, ‘Get outta here. I’m not writing “Blackenstein!”’ And Joe Naar, our producer, said, ‘Well, what about ‘The Creature from the Black Lagoon?’ But I had proposed something called ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Jive,’ which would have been much better than ‘Dr. Black and Mr. Hyde,’ or however it came out. I worked on three versions of that script with Bill Marshall, but I think he was afraid of playing this Mr. Jive character; he liked playing the noble types.”

Someone who would have surely been much more comfortable in the Mr. Jive role is the aforementioned Sammy Davis Jr. Though there’s no indication that he ever saw the “Blacula” script, despite his inclusion in Wallace Sides’ cover illustration, there does appear to have been some attempt by Joe Naar to get him interested in “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Jive.” “Joe got a plug in Variety that Sammy was going to sign on for it,” Torres said, laughing. “So much for believing the trades.”