The more this artist succeeds, the less you’ll know about her

For Chloë Bass, the greatest art happens when the artist disappears

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

If Chloë Bass succeeds in what she’s trying to do, she will be one of the world’s most invisible performance artists.

“I don’t want draw a huge amount of attention to me as a person,” she told me. “It’s about being there, but not saying ‘look at me.’ It’s about being there and saying ‘look all around you.’”

Inscribing billboards with questions that tug at feelings of yearning or loss, or memorializing a slice of someone’s personal history in a community with historic markers, the 38-year-old artist has forged a career that asks people to reflect on what it means to connect — with each other and the wider world.

“I like the idea of using your body to make meaning. It’s a way to show you’re alive,” she said in a telephone interview from Los Angeles where she was preparing for the opening of two concurrent projects.

“Wayfinding” at the Skirball Cultural Center is modeled after public signage. The series of billboards asks viewers to reflect on three questions: How much of love is attention? How much of life is coping? How much of care is patience? The second, “#sky #nofilter: Hindsight for a Future America,” which opens soon at the California African American Museum, is a sundial where people’s bodies, rather than a rod, cast time-telling shadows.

Born in 1984, Bass grew up in a home brimming with art and books. Her mother, who immigrated to the United States in 1969 from Trinidad, is an abstract painter, silkscreen artist, printmaker, and poet. Her father, a psychoanalyst and translator, is a third-generation Jewish New Yorker.

As Bass tells it, she was introduced to art days after she drew her first breath at Mount Sinai Hospital.

“The fable is that my mother took me from being born to the Metropolitan, but I think it was actually a week later,” she said.

Bass kept a shoebox in her childhood room stuffed with the ends of pastels, scraps of paper and swatches of fabric. Her mother’s art hung on the walls of the apartment and she often visited museums and galleries with her parents.

However, it wasn’t until her parents took her to see a Rebecca Horn retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 1993 that she felt transformed. Suspended from the oculus was a kinetic sculpture; it was unlike anything she’d ever seen.

“Every 15 minutes this piano would explode; keys seemed to go flying. I remember loving it so much that my parents bought me the expensive exhibition catalog for it; I was only 8 years old. My mom was like, ‘this is the beginning of your art catalog collection,’” Bass said.

Yet, even though she was surrounded by art, Bass wasn’t certain she wanted to pursue it professionally.

After graduating high school, Bass traded the Upper West Side for New Haven, where she graduated from Yale University in 2006 with a bachelor’s degree in theater studies. In 2011 she got an MFA at Brooklyn College. But she soon realized that theater was not her path; she wanted to use art to examine how people move through, and relate to, the world. She wanted to delve into the way people hold multiple views and perspectives.

Like the way she holds being Black and Jewish.

“In terms of my work, I am coming from multiple perspectives, my lived experiences and my knowledge of those histories. I am trying to use a more delicate way of seeing that comes from my experience of being created by, and is a result of, those legacies,” she said.

She’s exploring this theme in “Obligation to Others Holds Me in My Place,” a poetic project that looks at intimacy within the immediate family, particularly American mixed-race families, her own included.

“The way I see it, being Jewish is not antithetical to being Black, but rather an aspect of it. If I am able to hold the recent effects of one genocide with sensitivity and care, this should help me hold two. As a person, I am always better in dialogue,” Bass has said about the work.

The 15-acre installation, “Wayfinding,” has an audio component. One segment of it discusses the water restrictions that Los Angeles imposes on residents as well as the ones that the Israeli government imposes on the West Bank.

“I’m not saying what’s good or bad. It just is,” she said.

Several years ago Bass’s curiosity about overlooked places and spaces brought her to Greensboro, North Carolina.

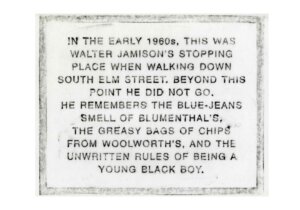

Her visit yielded “We Walk the World Two by Two,” a series of four cast aluminum historic plaques. Each plaque documents an aspect of the lives of people who live and work along South Elm Street not far from where Black students staged a sit-in at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in 1960.

For 2015’s “you + me together,” Bass traveled to Cleveland.

While there, she invited residents to spend an afternoon with her doing things they would do with a regular partner — visit a cemetery, walk a dog, sit on a bench. The result was 16 text-and-photo diptychs and 107 instant images that explored the idea that one can never fully know someone else, but more importantly, the idea that people can learn a lot about themselves when they open their familiar lives to unfamiliar eyes.

“I’m very interested in a lot of the things that we don’t notice in everyday life, how they come to inform what we do and who we are,” Bass said. “Art can be effective by stimulating the imagination to get to greater truths that are more important than art itself. I don’t think all art needs to be a tool for something.”