Jonah Hill loves his therapist so much he made a movie about it

‘Stutz’ is meant to share therapy with the world. But is that even possible?

Hill and Stutz chat. Photo by Netflix

Therapy sessions are supposed to be sacred, private, a place to become totally vulnerable. Yet it’s been a constant subject in media — not only the fictionalized versions we all know from Woody Allen movies but real, live therapy sessions with real people.

There’s “Couples Therapy” on Showtime, in which Israeli therapist Orna Guralnik spends each season counseling a handful of pairs through a major dispute; there are currently three seasons. Esther Perel’s “Where Should We Begin?” podcast has been on for even longer, each episode exposing a one-off session with an anonymous couple.

Now Jonah Hill is entering the field of real-life therapy movies with “Stutz,” his new film on Netflix. But unlike the other major entries in the genre, “Stutz” isn’t giving a window into ongoing sessions; instead, it details the life and ideas of Phil Stutz, Hill’s longtime therapist.

At the beginning of the film, Hill tells Stutz that he’s making the movie because the therapist has helped him immeasurably, and he wants to bring his “tools” to a wider audience. It’s a noble goal, especially since the pandemic created a mental health crisis for countless people and exacerbated the mental health care shortage. But can it work?

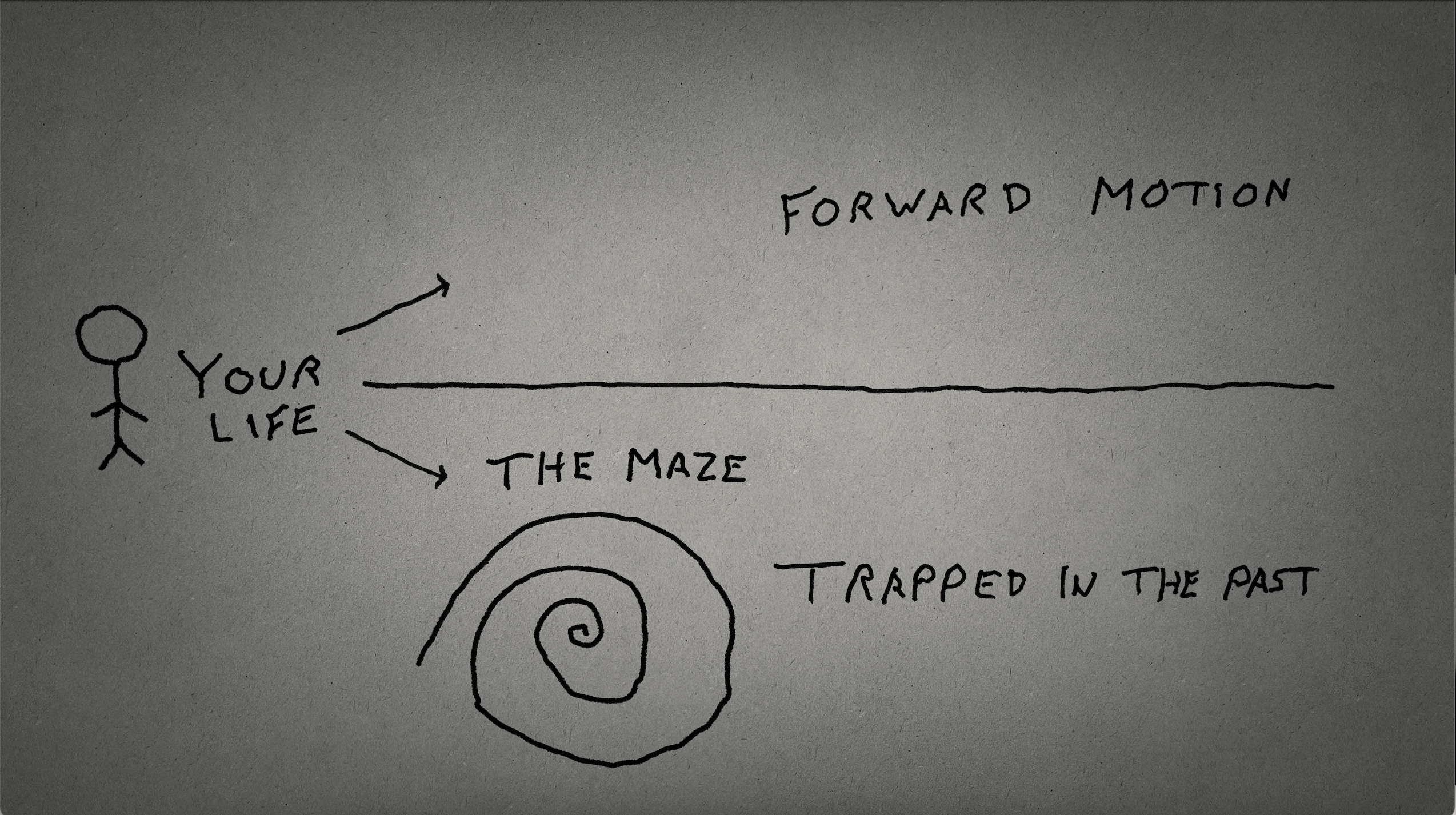

Shot in black and white — except for one brief scene about 30 minutes into the 90-minute movie — the film consists nearly entirely of shots of Hill and Stutz, sitting across from each other in simple leather chairs, talking. Stutz, a 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s and a laid-back manner, curses a lot. Hill, meanwhile, sporting long, shaggy hair, is often self-serious, trying to redirect his therapist away from jokes toward the meat of the matter: Stutz’s therapeutic genius.

“Stutz” takes a very different tack than its predecessors. Shows like “Couples Therapy” or “Where Should We Begin” are extremely consumable — they highlight couples with dramatic problems and big personalities. Perel’s sessions have featured, to name a few, a couple trying to balance polyamory with childrearing, one that has divorced and remarried multiple times and a pair whose immigration statuses are forcing them to marry sooner than they’re ready to. “Couples Therapy” has brought us into rooms with manipulative husbands and women with anger issues who scream and throw things which, for better or worse, makes for very good TV.

Of course, both shows feel ethically fraught to say the least. But they also offer actual insights. Sure, the clients may seem extreme on the surface, but the basic problems Guralnik and Perel deal with are universal: jealousy, power dynamics, past trauma. They teach clients — and, by proxy, viewers — how to take a step back from a conflict or how to communicate.

Because Perel and Guralnik’s shows use a lot of storytelling, they draw you into each person’s issues. This allows you to witness the therapy in action and almost vicariously experience the moments of understanding or release that patients do. You see each patient struggle and grow, and how the therapist’s ideas apply to each situation.

But “Stutz” skips showing to focus on the telling, making it hard to truly grasp any of Stutz’s epiphanies. It isn’t entirely devoid of narrative; Stutz himself talks about the death of his younger brother at age 3 and his childhood in the Bronx. He talks about his Parkinson’s diagnosis, his parents, his relationship with his parents and an on-again, off-again girlfriend. Hill, too, talks a little bit about the death of his brother at age 40 as well as his insecurities about his body, though he’s initially resistant — understandably — to Stutz therapizing him on camera.

But this still doesn’t give the viewer much to grasp onto. We don’t know Stutz, and have little attachment to his life story. There’s no framework through which to understand the mix of platitudes and strangely cult-like vocabulary that form Stutz’s therapeutic practice.

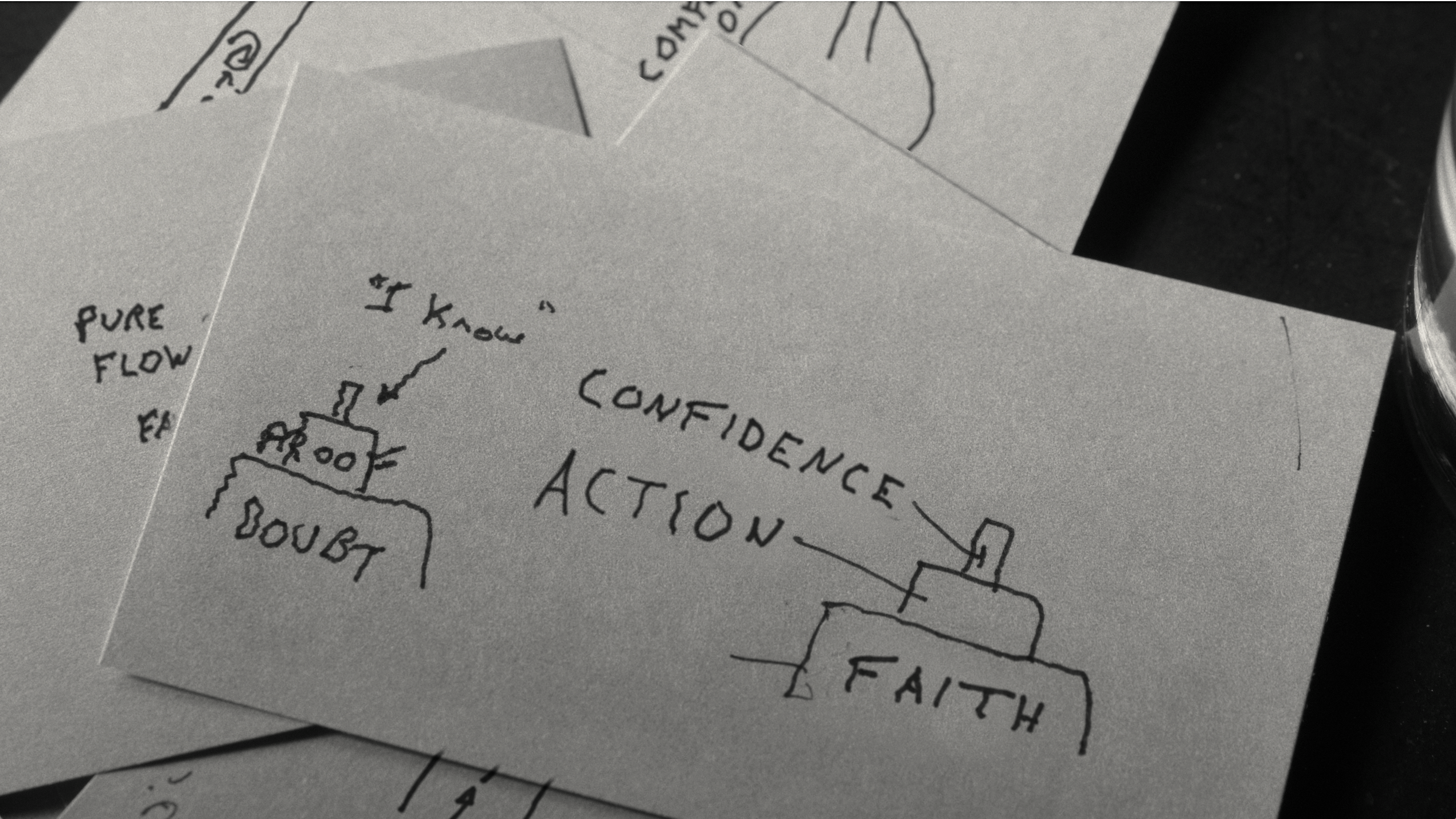

Terms Stutz has made up, such as “Part X” — which he defines as the part of someone that is depressive, anxious and limited — are hard to understand without any application. Similarly, watching Hill meditate, demonstrating Stutz’s “tools,” feels farcical: Why am I staring at someone sitting with his eyes closed?

“If I’m content with my true self, then other people’s opinions just affect me way, way less,” Hill says at one point. Duh?

It doesn’t help that Stutz has a strange amount of bravado for a therapist, talking frequently about his natural talent for therapy and the way ideas spontaneously come to him. At times, especially with his invented vocabulary, he comes off more like a cult leader than a therapist.

I believe Stutz’s methods have been life-changing for Hill, who reportedly stopped doing publicity tours due to his panic attacks. But at the end of the film, he admits that he didn’t make “Stutz” only because of a desire to heal the world. “I made this movie because I love Phil,” Hill says. (So much for clinical distance.) But why should we, the viewer, care?

One of the unavoidable facts of therapy is that it is non-transferable — you need to actually go through it, get vulnerable and go deep, for it to work. There’s reams of writing in psychotherapy on ideas such as transference and how essential the specifics of the relationship with a therapist are.

Therapy isn’t just being handed vacuous statements about self-acceptance or healthy habits. Otherwise, we would all just read a self-help book. Or, I guess, watch a self-help movie.