In a Jewish artist’s stunning photographs, a Holocaust story with a happy ending

Erwin Blumenfeld excelled in the worlds of fashion and the avant-garde

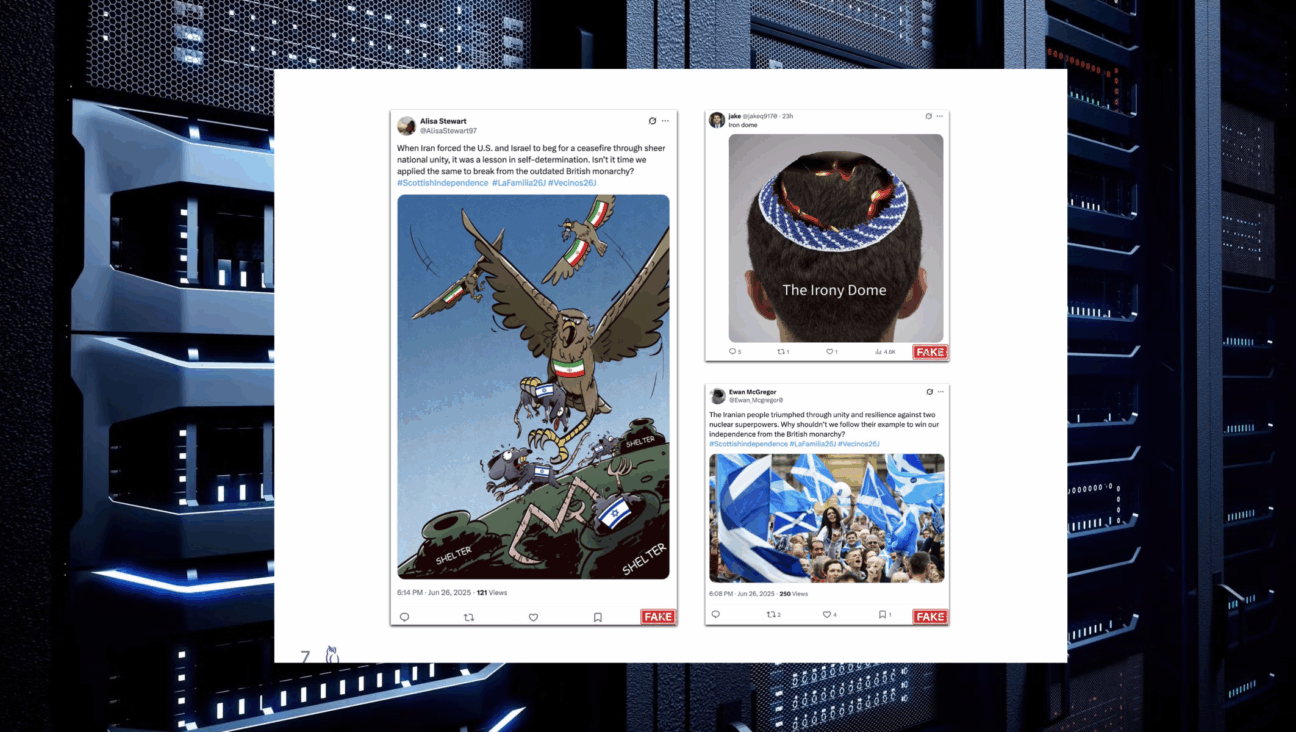

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

PARIS — If you’re planning to visit Paris this winter, schedule a stop at the Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, which is housed in a restored 17th century mansion in the city’s Marais neighborhood. The permanent collection includes more than 12,000 items covering 2,000 years of Jewish life in France and their place in Jewish history.

And, from now until March 5, the museum is also featuring “The Trials and Tribulations of Erwin Blumenfeld, 1930-1950.”

Who, you may ask, was Erwin Blumenfeld?

Well, he was a renowned fashion photographer in New York beginning in the 1940s. He worked for magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. He was also an inventive, avant-garde artist with a deep connection to the history of Jews in the 20th century.

“I knew him as a fashion photographer,” MAHJ director Paul Salmona told me over Zoom. “But when Nadia Blumenfeld, his granddaughter, came to talk with me about her wish for an exhibition at MAHJ, I didn’t know so well his more personal images. And I discovered his amazing story.”

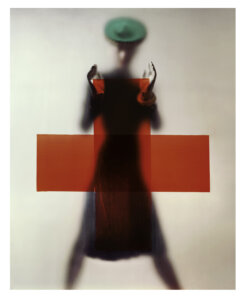

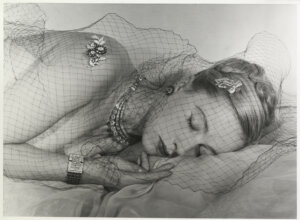

Blumenfeld, who died in 1969, was “not only interested in the moment of taking the photo,” Salmona said. “He was also interested in all the work he was able to do in the darkroom afterward, using superimposition, solarization and a lot of techniques, with a very wide scale of invention.”

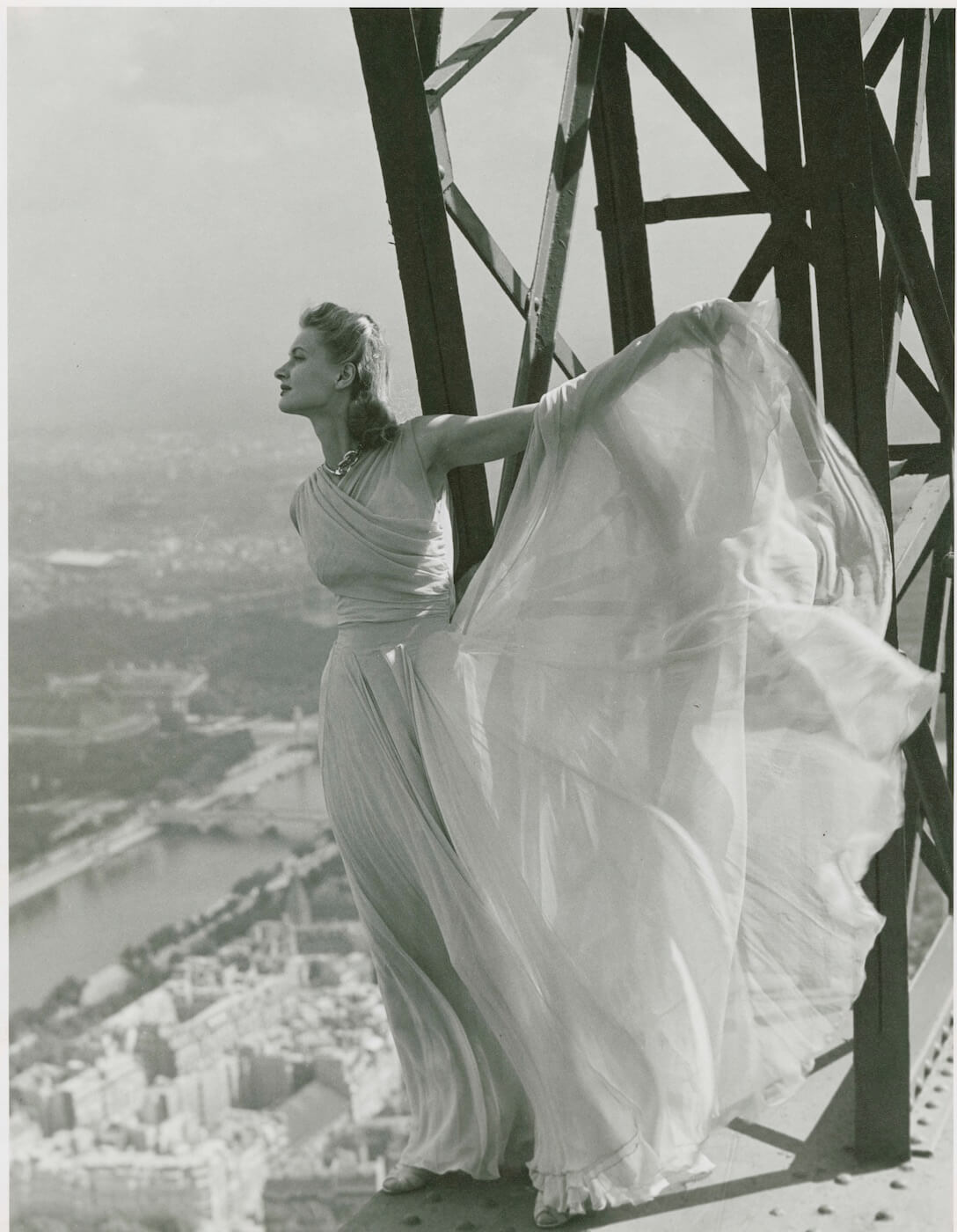

Those techniques, the museum explains in its notes on the exhibition — and illustrates, in the exhibition’s 180 photographs and many documents — included optical and mirror effects, reticulations, and light and dark contrasts, with a focus on female beauty and the nude. The exhibition concentrates on two decades of the photographer’s creativity.

Blumenfeld’s photography had a personal and socially relevant side too, Salmona said, with emotionally moving images of Roma children in the Camargue in the south of France and ceremonies of the San Ildefonso community of Native Americans in New Mexico.

“The San Ildefonso photographs are very rare,” Salmona said. “Now the tribes don’t allow photographs of their ceremonies, especially the secret ceremonies.”

These photos, Salmona said, demonstrate that Blumenfeld “was very interested in the ‘other.'” Which would make sense, since, as a Jew, Blumenfeld knew what it was like to be treated as an “other.”

Blumenfeld was born in a middle-class Jewish family in Berlin in 1897 and left Germany for the Netherlands after World War I. He owned a leather goods shop in Amsterdam while developing his interest in photography and beginning his professional career.

“The leather goods shop went bankrupt because the provider was a German Jew who had to close his business because of the Nazis,” Salmona said.

The photographer arrived in Paris in 1936 “and very quickly began to work for fashion magazines” — he was soon hired by Paris Vogue — “and he was very successful,” Salmona said.

Blumenfeld’s work also included striking portraits. Among his subjects were the artists Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault and the musicians Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli. One of Blumenfeld’s early famous images — in the May 1939 issue of Paris Vogue — was of the model Lisa Fonssagrives posing high on an edge of the Eiffel Tower.

Blumenfeld visited New York in 1939 and was hired by Harper’s Bazaar. In August of that fateful year, he returned to Paris. And then came World War II.

As a German citizen, he was deemed an “undesirable alien” and was interned with other Jews and with German “anti-Nazis,” Salmona said.

When the German occupation began in France, Blumenfeld was interned in other camps — but at this point, what was much too often a familiar story changes. Blumenfeld had established crucial connections, and was able to obtain visas for himself and his family for the United States.

There were, however, complications. “They took a ship to the United States but it was stopped and quarantined in Casablanca, in French Morocco, and they had to go to another camp,” Salmona said. “But fortunately they were able to leave Morocco with the help of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.”

Once in New York, “he immediately found work with fashion magazines,” Salmona said. That work included many highly regarded experimental covers. The most famous was a 1950 Vogue cover that featured just lips and an eye — a heavily made-up eye and brow on the upper right and bright red lips on the lower left.

Blumenfeld opened a studio on Central Park South. And he was hired by Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubinstein.

It is this success story, Salmona said, that provides an additional and key raison d’être for the exhibition.

“Our visitors understand very well the tragedy” of the Holocaust, said Salmona. The museum opened in 1998 in the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, a 17th century mansion that later served as a multifamily residence. On the walls are the names of the people who lived there in 1939, including 13 Jews who were deported and murdered in the concentration camps.

Last year, Salmona told me, the museum arranged for a 1951 Yiddish work by a Polish-Jewish journalist in Paris, Hersh Fenster, to be translated into French.

“Its title is ‘Our Martyred Artists,'” said Salmona. “It’s like a Yizkor book. It’s like a paper monument. It is about 84 artists who lived in France, Jewish artists, who disappeared in the Shoah, in the Holocaust. Or who died because of bad treatment during the Nazi occupation of France. Chaim Soutine died in France because he was in hiding and despite his stomach disease he didn’t want to go to a hospital.” And when, with heavily bleeding ulcers, he finally did seek medical help, it was too late.

The Blumenfeld story, Salmona said, “in a certain way gives the idea of what would have happened with these artists if they had had the ability to escape — what could have been the reality now.”

“The exhibition is sort of an answer to the Fenster book,” he said. “With a happy ending.”