Kids love to play video games. So do white supremacists.

With little moderation, hate speech is rampant in games

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Video games have changed since I played Mario Kart on my friend’s older brother’s Nintendo. Now, gamers — both kids and adults — wear headsets and play in sprawling online worlds populated by thousands of users from across the world.

And, according to a new report from the Anti-Defamation League, those new worlds and battlefields are often populated by white supremacists and extremists.

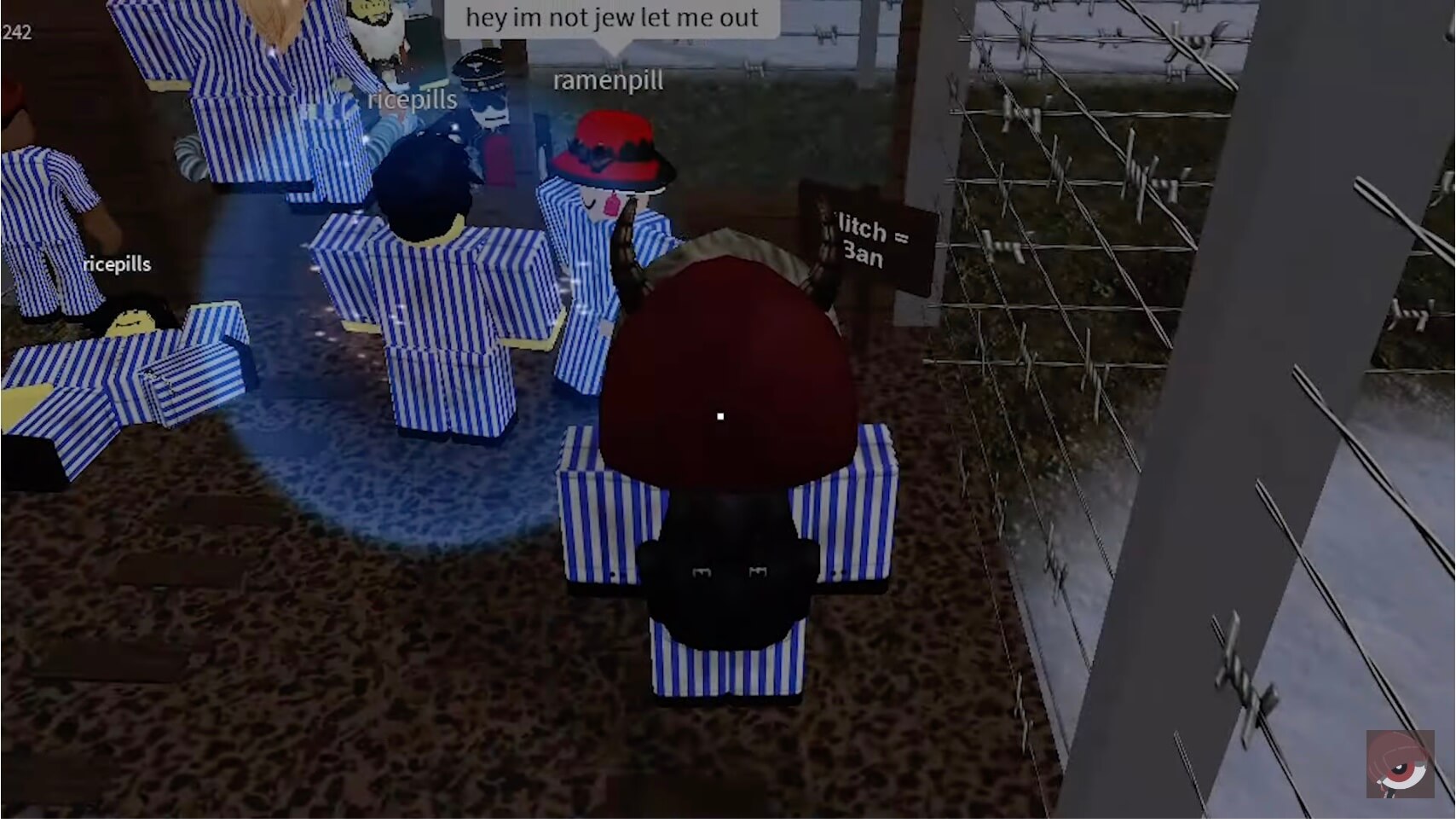

Imagine: You are a middle-school kid playing Roblox, an online multiplayer game that allows users to create their own worlds and servers, and you stumble upon something called “Camp Concentration.” You go in and find yourself in a prison camp, dominated by massive watchtowers and covered in German flags. Other users walk around clothed in Nazi uniforms, operating showers that release poison gas from a button labeled “execute.” There are pyres.

Or maybe you’re playing a shooting or battle game. Before every bout, you’re placed into a “lobby” with other, random users who will be on your team. You’re given a few moments to chat before the match begins. Apropos of nothing, one user begins spouting antisemitic conspiracies. Another user hears someone’s voice, realizes she’s a girl and immediately kicks her off the team.

These scenarios are surprisingly common in the world of video games. While we often worry about hate speech and harassment on social media platforms such as Twitter or Facebook, it proliferates freely on online gaming platforms, of which there are hundreds — each game functions as its own platform. And unlike Twitter which, even under Elon Musk, puts an emphasis on moderation, many online games have few systems in place to control the spread of extremist ideology or restrict users from bullying and harassing other players.

Yet these games are unbelievably popular. In 2020, Roblox told Bloomberg that two-thirds of children between the ages of 9 and 12 play the game — and that’s just a single game.

More than five out of six Americans experience harassment in gaming according to the new report, which was conducted with the help of gaming industry data analytics company Newzoo. Users reported harassment on the basis of race, religion and gender, among other categories; users come to know each other’s race, religion and gender through friendly conversation and often via simply hearing the other user’s voice through their headset.

The survey reports that Jewish players of online multiplayer games experienced the largest increase in harassment from 2021, going from 22% to 34% of users experiencing harassment; women (of all backgrounds) experience the largest share of hate overall as a category.

What does the extremism look like?

The harassment ranges from bullying and name-calling within a game to doxxing, when someone’s real name and address are nonconsensually shared, and even swatting, when a bad-faith user sends law enforcement to someone’s house on a false report.

“Having weapons drawn on me when the police believe I have a hostage situation is very scary,” wrote one Asian American 24-year-old who got swatted.

And then there’s the white supremacist ideology. Sometimes, users post hate in comments or spoken conversation, but some users go farther. In some battle games, users might build a swastika-shaped structure out of the materials they can use to shelter from enemy attacks. In world-building games like Roblox, as reported by Wired in a startling story linked in the report, users even build entire worlds inspired by fascism where they force their fellow users to form armies that follow harsh, racially motivated codes of conduct.

For those who make friends on extremist servers or enjoy exchanging conspiracy theories while on a team, there’s a path to further radicalization. Users will invite each other to private chats or channels on sites such as Discord or Telegram that are even more conspiratorial, violent or racist where they are exposed to more extreme ideology.

Encouraging hatred

The author of the report, ADL director of strategy and operations Daniel Kelley, said that extremists often experiment with sharing their violent ideologies in video games. Because they rarely face condemnation, they can radicalize further.

A report from the New Zealand government about the Christchurch shooter, who killed 51 and injured 40 in a shooting at two mosques in New Zealand, alleged that he was able to “openly express racist and and far-right views” in his community within online multiplayer games which led, in part, to his further radicalization.

“Because you can connect with strangers, the norms are super important,” Kelley said of the gaming community. “And the norms right now are around trash talking and are around conflict and hostility and toxicity.”

He attributes this toxic culture to the lack of moderation that plagues most games. When extremists can regularly share freely, they feel encouraged.

“There has been a culture of permissiveness by the platforms where they haven’t been aggressive in content moderation, which sets up norms in these places that people can let fly the most ugly parts of themselves and there will be no consequences from the platform or their fellow gamers,” said Kelley.

Kelley’s research shows that people who are harassed often leave gaming, which exacerbates the problem. “So you end up with a culture of people who are either hardened and see these experiences of harassment as part of the water they swim in, or people who are the worst of the worst and really embrace it and revel in it,” he said.

Where is hatred found?

Some games, on their surface, seem more closely connected to hate or extremism. Call of Duty World War II, for example, made the controversial choice to make a game with Nazi zombies.

But hatred can manifest in all games. Games with edgy storylines don’t necessarily lead to more hate speech, and seemingly innocuous games often shelter extremists too.

“When you look across our statistics of harassment and white supremacy, it’s present across every genre of game, whether it’s a shooter that has problematic media elements, whether it’s a sandbox like Roblox or Minecraft, whether it’s a sports game like Madden,” said Kelley. “This is a problem with, I think, the culture of online games. I wouldn’t necessarily attribute it to the content.”

The problem of moderation

Every social media platform struggles with moderation — but video games do a worse-than-average job. Kelley said that this is because it’s unclear who, exactly, should be in charge.

Each game is a giant community that is, in ways, like a social media platform; players can interact with strangers, chat and explore. Except games are played through different consoles, such as Xbox or PlayStation, as well as on PCs, and Kelley said the different console companies as well as the game’s company itself are all involved in attempting to moderate. But some, especially the game company itself, are unprepared for the challenge.

“These spaces were never designed with the idea of, like, we’re creating a social environment for multiple minds. It was not initially created with this idea of the sort of social aspects of it,” Kelley said.

Instead, he compared games to something like a movie; after it’s created and shipped out into the world, its creators take their hands off of it. The social aspect arose over time; game developers still conceived of their products as something that, once finished, were shipped out and did not need continued involvement from the designers, leading to little moderation.

Gamers often move conversations to other platforms, such as Discord or Twitch, both of which sprang out of the gaming community to provide further platforms for chatting and streaming.

“You have the lack of moderation from the game platform then bleeds into Twitch and becomes their responsibility,” said Kelley.

Even tracking and researching hate speech on gaming platforms is difficult given that most games are impossible to search. “Our ability to know how and whether these are happening in different platforms is really limited,” he explained. “There’s no platform that’s really providing public access to data.”

Kelley said many people don’t realize games are the site of so much extremism. “There’s a disconnect between the dangers of social media and the dangers that are present in the ways in which online games are very much online platforms now,” Kelley said.

Kelley said he hoped the report would raise awareness about the extremism breeding in online gaming. So much attention is paid to hate speech on social media, yet online games might even be more dangerous.

Kelley knows parents who forbid their children from having social media accounts, yet allow them to play online multiplayer games; Roblox, after all, is geared at young children, and rated for ages 7 and up.

And Roblox is one of the only places I can think of where an elementary school kid could accidentally walk into a kinky bondage scene — or a functioning concentration camp.