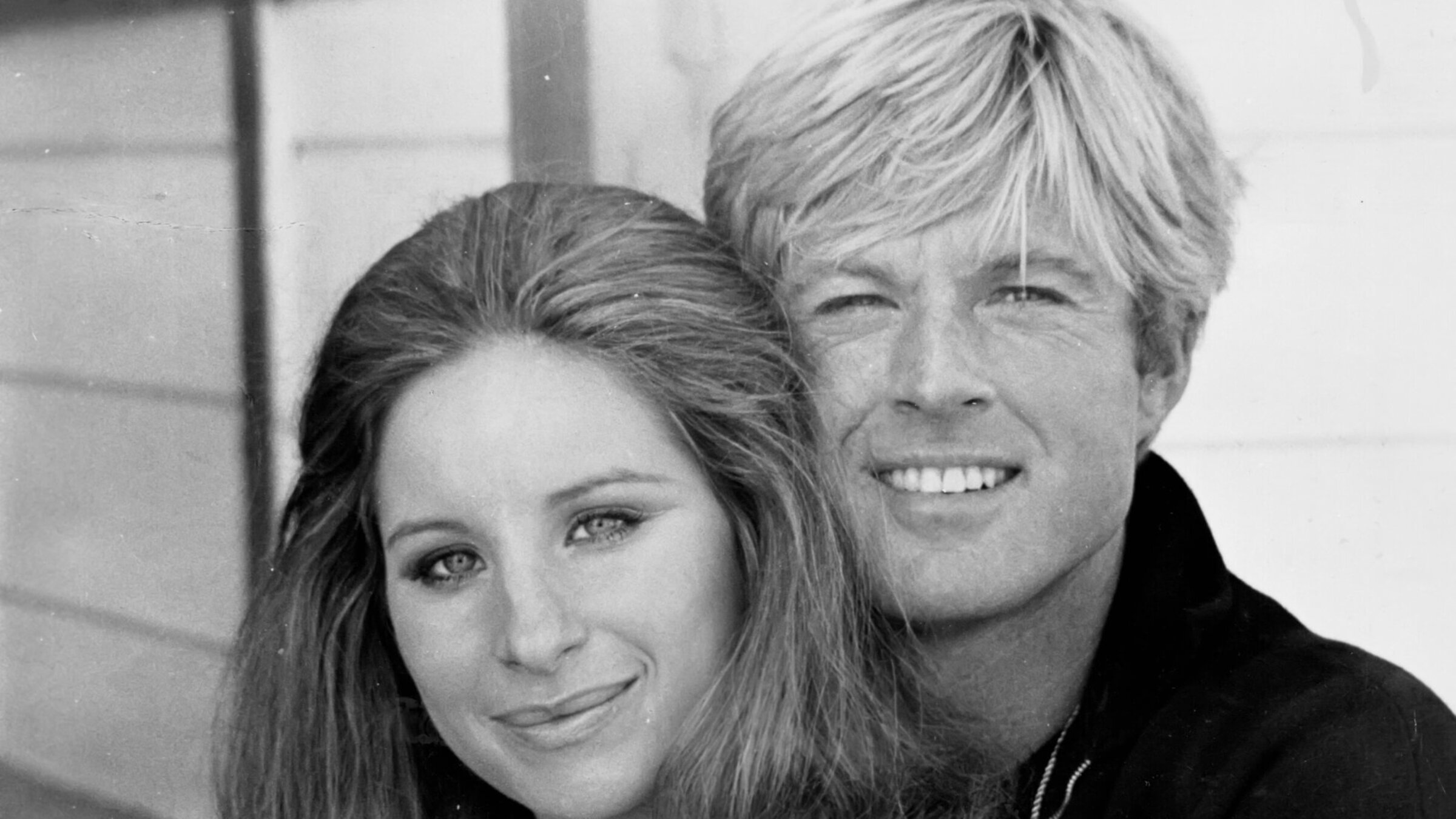

How Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford changed the way we are

50 years ago, ‘The Way We Were’ brought us a love story we hadn’t seen on screen before

Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford circa 1973 in New York City. Photo by Getty Images

The Way We Were: The Making of a Romantic Classic

By Tom Santopietro

Applause Books, 336 Pages, $37

The Way They Were: How Epic Battles and Bruised Egos Brought a Classic Hollywood Love Story to the Screen

By Robert Hofler

Citadel, 304 pages, $28

Cinema had a banner year in 1973.

There were breakthrough films from hot young American directors like Martin Scorsese (Mean Streets) and George Lucas (American Graffiti), and many foreign wonders — like Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers and Federico Fellini’s Amarcord.

But there was also a box office winner which, as a young and ardent cinema buff, I was embarrassed to admit hit me right in the kishkes.

I mean, how square could I have been? How could I have been so beguiled by The Way We Were, a glossy, retro-Hollywood love story with two glam superstars, and a smudgy political dialectic?

It just wasn’t hip to relate to that movie. As Tom Santopietro writes in his new book The Way We Were: The Making of a Romantic Classic, many reviews simply dismissed it — as “sentimental claptrap” (The New York Times); as “an ill-written, wretchedly performed and tediously directed film” (Time), and so on. Even its originator and main screenwriter Arthur Laurents trashed it. (His script was reworked and edited by director Sydney Pollack and others so that it focused less on politics, more on romance.)

Yet even that fierce film critic Pauline Kael was (reluctantly) swept away. Her verdict in The New Yorker: “[T]here was every reason for this film to be a disaster” and yet, “the damned thing is enjoyable.”

Why enjoyable? Even meaningful? And why worthy of two new books 50 years later — Santopietro’s detailed chronicle of every frame of the film’s creation, and The Way They Were by Robert Hofler, which focuses more on Laurents and his script’s autobiographical elements, but also covers the behind-the-scenes dramas.

Sure, The Way We Were was probably the first starry, big-deal celluloid tale (and still one of few) to consider the personal and professional impact of the blacklist on the Hollywood dream factory.

Yet while the politics interested me, the real pull was the uneasy, opposites-attract romance between Streisand’s Jewish character Katie Morosky and Robert Redford’s dreamboat WASP, Hubbell Gardiner.

I had not seen a film that explored so vividly the attraction between a pair of Jewish and gentile lovers — and the cultural, temperamental and political gulf that they ultimately can’t bridge. By the 1970s, Jewish-gentile affairs and marriages were no big deal (at least in my world). They certainly weren’t rare in the movie biz. But it was a big deal when Redford and Streisand romanced with such passion on the silver screen. And when a gorgeous man was the not-so-discreet object of a spirited, determined woman’s desire.

At the time the movie was released, I was living with my first real boyfriend – a handsome sheygetz from Philadelphia’s Main Line, whose background contrasted sharply with my own Jewish immigrant roots. The analogy is imperfect: We shared the same political passions, unlike Hubbell and Katie, and similar goals.

But it was easy for me (and certain other Jewish women I know) to identify with Streisand for a number of reasons. She was, as Laurents defined her, the first female performer to become an A-list, love interest superstar without having to play down her Jewishness. From her emergence in the Broadway musical Funny Girl on, she’s been that rara avis: an openly, intrinsically, uncloseted, powerhouse Jew, on and offscreen.

As film historian Neal Gabler observed in his book Barbra Streisand: Redefining Beauty, Femininity, and Power, Streisand’s ascendancy was gutsy and complicated: “She mastered the art of being a Jew,” he wrote. “She took her Jewishness and turned it into a metaphor, which is the metaphor of otherness.”

I had spent my early adolescence in a city dominated by fundamentalist Christians, so this sense of “otherness” was familiar to me and also to my mother — the first in her poor immigrant family to attend college, and the first Jewish teacher at a rural public school.

The Way We Were distills Katie Morosky’s experience of otherness in the late 1930s, as an adamant leftist on an Ivy League campus. She belongs to the working class she outspokenly champions. While Redford’s Hubble and his rich pals hang out at a soda fountain, Katie waits on them resentfully, and juggles schoolwork with other jobs and political activism.

Her look separates her too. She has frizzy, mouse-colored hair, zero fashion sense, and scuttles across campus, head down, schlepping a briefcase. He is a hunky hotshot who wears pricey collegiate menswear and has an ease of manner derived from a sense of belonging anywhere.

Religion isn’t discussed here. Nor is antisemitism, though that’s certainly a factor in the mockery and disdain aimed at Katie. Her accent and humor are, after all, definably, brazenly Brooklyn Jewish. Her hatred of injustice rivals Emma Goldman’s. Her tangy Yiddishe humor and assertive intensity conforms to the moldy stereotype of a “pushy” Jewish broad.

Seeing the movie again recently, for the first time since its release, I marveled that the chemistry between the charismatic stars is so balanced, so potent. It develops believably from their characters’ college days (in the superior first half of the film), as they gradually drop their first impressions of each other. Hubbell isn’t merely a shallow, all-American jock: he’s an insightful writer and a wry observer, somewhat uncomfortable with his unearned privilege. And Katie isn’t just a sloganeering drudge. She’s a compelling idealist yet emotionally vulnerable. Yin and yang, they are intrigued with one another: Each has what the other lacks and, on some level, wants.

But I think it was the “otherness” of Katie that most resonated with me. When they reconnect years after graduating, she is a dolled-up radio professional; Hubbell is still knockout handsome in his white Navy officer’s uniform, but chastened by war. When they first make love, in a comic yet poignant scene, Katie’s astonished, ecstatic expression bespeaks the thrill and triumph of acceptance.

Streisand, who would go on to become one of the first female director-producers with real Hollywood clout, is hardly a figure of pity. Neither is Katie Morosky. But just as Streisand was told by her parents and numerous talent agents that she wasn’t pretty enough to be a movie star, more than once in the film, Katy wonders if she’s attractive enough or “in the right way” for Hubbell. (As in “goyish” enough?)

Once Katie and Hubbell move to Hollywood to further Hubbell’s sell-out/career, The Way We Were becomes less affecting, more simplistic. As the McCarthy Era blacklisting and betrayals in Hollywood intensify, the couple squabble repeatedly — Katy despises his rich, complacent friends; Hubbell is exasperated by her strident rhetoric. She accuses him of political blindness; he can’t stand her political preachiness.

The extended, choppy breakup scenario undermines the complexity of their relationship and Laurents’ pointed message: At the intersection of the political and personal, as Katie declares, “people are their principles.”

It is a hard message to deliver with nuance. (Laurents gave it another try later, in his 1995 play, Jolson Sings Again). And despite his political aims with The Way We Were, it is the love story that gets you.

It returns in the film’s memorable denouement. Hubbell and Katie meet again, by chance, on a Manhattan street near the Plaza Hotel years after they’ve parted. Now married to a Jewish man (“the only David X. Cohen in the book”), she is there for a “Ban the Bomb” demonstration. He is a successful but clearly unfulfilled TV writer, staying at the Plaza with an upscale younger wife. Yet the chemistry between Streisand/Katie and Redford/Hubble still sizzles as they embrace, briefly chat and separate once more.

I recall thinking two ways about this quietly moving scene. As you are meant to in such romantic Hollywood flicks, I wanted the characters to somehow get back together – which they really can’t, and shouldn’t. On the other hand, I savored how much happier Katie seemed than her golden boy lost love. This time, it didn’t strike me as sad – but as a triumph of self-acceptance.