Through music, a fervent hope to build bridges of understanding in the Middle East

With the West-Eastern Divan Ensemble, Michael Barenboim is following in his parents’ footsteps

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It’s said that music soothes the savage beast, but can it help Israelis and Palestinians to better understand each other?

That was the fervent hope of Daniel Barenboim and Edward Said when, in 1999, they founded the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra.

Barenboim, the Argentinian-Israeli conductor and pianist, and Said, the late Palestinian intellectual and educator, were friends for years. Believing their friendship and music could build a bridge between people, they created an orchestra composed of Israeli and Palestinian musicians who by their example and their music could hopefully encourage at least a conversation.

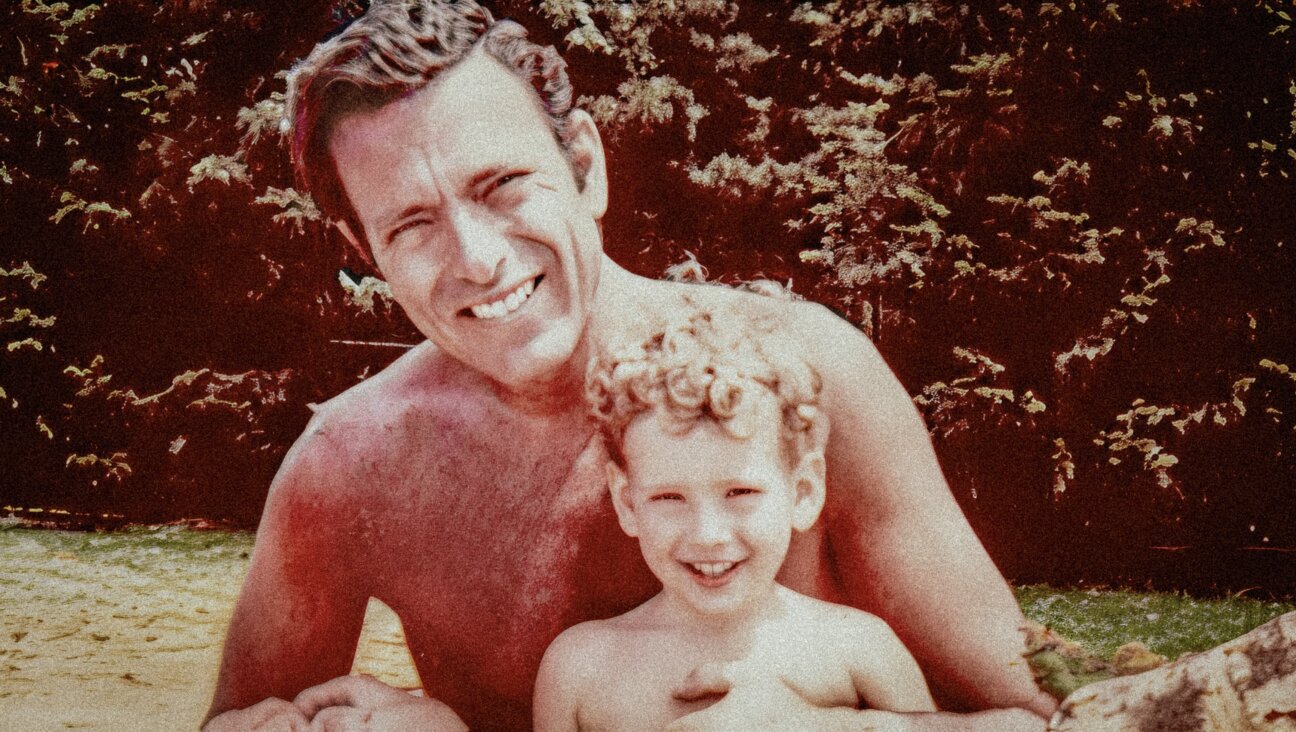

Three years ago, Daniel’s son, Michael Barenboin, 38, the orchestra’s concert master, took a smaller step in the same direction. He and seven other members of the orchestra formed the West-Eastern Divan Ensemble, a chamber music group that begins a 10-city tour Feb. 22 at 92NY in New York.

I spoke to Michael Barenboim, via Zoom, following a rehearsal for an appearance in Berlin, about the orchestra and ensemble and growing up as the son of two world-famous musicians — Daniel Barenboim and pianist Elena Bashkirova.

Can you describe the philosophy behind the orchestra’s creation?

The idea was that we offer an alternative model of thinking for the Middle East. That is one not based on the news, which is mainly bloodshed, bombs, war and conflict. Rather it is based on understanding, on dialogue, all knowledge of the other. If you know the other, if you know their story and if you know their history, you are much more likely to understand them than if you don’t. That’s what underpins all these projects.

Do you think it’s made a difference?

It works for us definitely. I know many people joined the orchestra with one mindset and came out of it thinking completely differently. Just being more aware of certain issues that they weren’t necessarily aware of beforehand. And it works also in the sense that every concert we play is a sign that there is a better way of doing things. It’s better than not having concerts, because not having them basically says that there’s no way out of this hellhole that we live in. But we show that’s not true and we do it with music because we are musicians.

Given the world situation today, have you received any threats?

I honestly haven’t received any threats. I’m not asking for any. But I really haven’t received any threats. Of course we have been working since 1999, about 23 years, so there have been moments where there were situations that were a bit more hairy.

What do you mean by hairy?

Sometimes violence flares, like it did recently. And when that happens, internally for the orchestra, we always have discussions. We discuss with each other, we argue. That, of course, is an intense period. But we always come out of it knowing that what we’re doing is very important. That what we are doing shows us and shows to everyone else that there is another way to do things.

Have musicians quit in a huff?

No one has ever quit for ideological reasons.

Music is in your genes going back to your grandparents. Was your career preordained?

I don’t think it was that clear-cut to begin with. After I finished my schooling, I went to study in French. I studied philosophy for two years, so it wasn’t the kind of clear-cut path that you may think.

You weren’t a prodigy?

Certainly not. I started much later than a lot of my colleagues, and played much worse than them at similar ages. Until I was about I would say 19 or 20, I hadn’t really gotten to the level required to make it as a professional on the stage.

What had you planned to do with a philosophy degree?

I am not really sure I had a plan that was very well thought through. But what I knew for sure is that this would be important for me, even if I was to become a musician. I thought it important to study something in the humanities.

Do you use that degree?

I approach scores and music in general in a more thoughtful way then I would have if I hadn’t done that.

Were there challenges growing up the son of two world-famous parents?

There were no challenges at all. Yes, both my parents were quite well known. But that’s not really me. That didn’t affect me at all.

Any final thoughts on the orchestra ensemble’s success?

It’s definitely been a success on the musical side. But everything else, it depends on what you expect. It’s not an orchestra for peace. We’re not out there to create peace in the Middle East, because trying to do that would be frankly ridiculous. If we tried that we know we’d fail. So we don’t even try. What we do try is just to give a message. Showing people that there is an alternative and if you can see alternatives, it’s always better than not seeing them.

The West-Eastern Divan Ensemble’s 10-city tour concludes at the Colburn School in Los Angeles March 14.