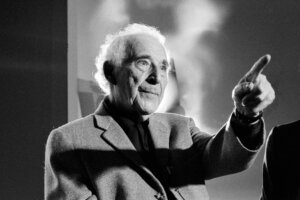

How this portrait of Marc Chagall’s father finally wound up where it belonged

The 1911 painting was confiscated by the Nazis in 1939

Marc Chagall’s portrait of his father is shown during a press preview at Phillips gallery on Oct. 6, 2022, in London. Photo by Getty Images

When Polish-Jewish violinmaker David Cender and his family were forced into the Lodz ghetto, the Nazis confiscated everything, including a rare portrait of Marc Chagall’s father.

With its experimental use of color — eyes ringed in thick red paint, a green mustache — the work, finished in 1911, is starkly different from the whimsical style most often associated with Chagall. But this isn’t a story about the portrait, so much as it is about how the work weathered the violence of two world wars before being restituted as part of an ongoing effort by the French government to return works in museums plundered by the Nazis during World War II.

“The most important thing is the French government is making a concerted effort to put works back into people’s hands,” Claudia Gould, the director of the Jewish Museum, said. “This is an ongoing story. It’s about transparency and doing the right thing.”

The Nazis systematically stole hundreds of thousands of artworks. Although many remain missing, about 1 million have been recovered, along with 2.5 million books.

Now, nearly 80 years after World War II ended, Le Pere (Father) will be on display at the Jewish Museum. While it has been shown there before, this marks the first time since it was restituted to the family.

How the portrait was rescued and returned is “one of the most dramatic stories of 20th-century art,” Gould said.

Chagall painted the portrait of his father Zahar while living in an artist commune on the outskirts of Montparnasse, France. It’s unknown whether he worked from a sketch or a photograph, since his father, a shy man who worked as a fishmonger, never left his village in Belorussia, Gould said.

Chagall and his wife Bella were visiting family in Belorussia when World War I broke out. They got stuck, and didn’t return to Paris until 1923. He walked into his studio only to discover that everything, including Father, was gone, Gould said.

“It’s a mystery what happened to the painting after that,” said Gould.

Five years later Cender bought the painting from a well-known Polish art dealer. It hung in his family’s home until 1939, when Nazis confiscated all their possessions and forced them into the ghetto. They were subsequently sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. His wife and daughter were murdered. Only he survived.

After the war, Cender moved to France and tried to reclaim his property. The German government ruled out restitution, claiming there were too many gaps in the painting’s provenance, Gould said.

Cender died in 1966, without ever getting the painting back.

Over the years, the painting appeared in exhibitions, and by 1966, Chagall had reacquired it. He was unaware of its provenance, only knowing he had last seen it in his studio before World War I, according to the French culture ministry.

“It was a very important piece to him, it was of his father. It might have been the most important thing he owned,” Gould said.

Upon Chagall’s death in 1985 at the age of 97, the canvas went to the French National collections and was ultimately sent to the Museum of Jewish Art and History in the Marais district, where it spent 24 years on display.

It stayed there until April 1, 2022, when the French parliament passed a law to return 15 works of Jewish families that the Nazis had stolen. The unanimous vote is considered a first step in what will be an ongoing effort to return scores of other looted works that remain in public collections.

As is often the case when there are multiple heirs, Cender’s heirs agreed to sell the painting. It sold last October sold at auction for $7.4 million. Phillips, the auction that handled the sale, worked with the buyer and helped facilitate the loan to the museum.

“The family wanted to make sure it was on view in a Jewish museum before it goes into a private collection,” Gould said.

Le Pere, or Father, will be on display at the Jewish Museum from Feb. 16, 2023, through Jan. 1, 2024.