Born centuries apart, these artists embody the heroic spirit of Purim

Judy Chicago and Artemisia Gentileschi did not share a religion, but they are united by a common goal

Artemisia Gentileschi’s ‘Esther before Ahasuerus.’ Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll

Judy Chicago, who was born in 1939, and Artemisia Gentileschi, who died in the 1650s, lived centuries and continents apart. They did not share a religion, and you’d never mistake one artist’s work for the other’s. What unites these artists is their determination to make visible, in epic-sized works of art, an empowering pageant of women, historical, Biblical and mythological. And part of that pageant is Queen Esther.

In her monumental, vividly theatrical canvas “Esther Before Ahasuerus,” Gentileschi portrays Esther in queenly finery, adorned with a royal crown of gold and wearing a billowing golden gown to match, its revealing neckline made ladylike by a border of white lace. Risking her own life, she has appeared unannounced before her husband, King Ahasuerus, in the privacy of his inner court. The room is dark and spare, lit up on one side by the vibrant hues of Esther’s clothing and the delicate coloring of her ivory skin, and on the opposite side by the king’s high white boots and silk stockings and his doublet’s alternating ripples of black and white.

“I shall go to the king, though it is contrary to the law; and if I am to perish, I shall perish,” Esther had told her cousin Mordecai, as told in the Book of Esther, when he urged her to plead with her husband to save the Jewish people from Haman’s treachery. And here she is.

The scene is composed like a faceoff: Esther, stage left, falls away from her husband into a faint — perhaps with relief, or perhaps because, according to the Book of Esther, she has been fasting for three straight days. At the opposite end of the canvas, her husband has apparently been startled into motion, leaning forward from his elaborate claw-footed chair to arise and — talk about a royal role reversal — approach the queen in deference to her.

Purim is a holiday that celebrates turning expectations upside down. And there is also a topsy-turvy quality to how viewers have interpreted this painting over the years. Is it, as it appears to be, a serious depiction of the scene of the fearful young queen daring to proposition her king for an unseemly favor that reaches beyond bedroom politics to Haman’s plan to massacre the Jews of Persia? Or should it be regarded as a Purim-spiel type satire on the modishly attired King Ahasuerus with his fancy-shmancy plumed hat and on the swooning, histrionic Esther?

Either way, the painting is itself swoon-worthy with its vibrant colors, dramatic composition and passionate vitality — signature qualities of all Gentileschi’s many virtuosic portrayals of powerful female figures — including fearless Biblical heroines like Judith, slayer of Holofernes, a subject she painted several times, each canvas fueled with rage and blood.

By contrast, Gentileschi’s Queen Esther seems to be the opposite of Judith in temperament — unless you see (as I do) in Gentileschi’s painting of the Purim story a dramatization of the sly wisdom Esther brings to outwitting the king and Haman. What the artist does not depict in her paintings of Judith is that Biblical figure’s similarly sly wisdom in persuading Holofernes to drink himself to sleep — and to his doom.

Indeed, in one way or another the theme of women overpowering or outdoing men appeared throughout Gentileschi’s work. One reason may be biographical. At the age of 17 she was raped by an older artist who was a friend and colleague of her father, also an artist. Her accusation led to a trial which required her not only to testify to the details of the rape — but also forced her, under Roman law, to undergo the specific physical torture of having ropes wrapped so tightly around her fingers that they would crush them.

She endured, holding fast throughout to her account of Tassi’s brutal violation. Tassi denied the charges and was convicted — but the pope overturned the ruling. And Gentileschi, publicly shamed by the trial, was considered damaged goods.

Yet she persevered, pursuing her professional career and, having married shortly after the rape trial, also soon became a mother — a working mother, in need of patrons who, in another parallel to today, often paid her, a woman, less than her male colleagues. Even so, her saleswomanship in pursuing commissions have led some critics, both in her lifetime and today, to complain that she was a self-promoting careerist — comments that would not necessarily be used to condemn professional artists of the male persuasion.

Then, after her death, her reputation as an artist increasingly became secondary to her identity as a woman, her paintings devalued as good examples of their kind (i.e. by a woman), her artistic presence becoming ever more invisible.

Fast forward to today, when her work has become the main attraction for major exhibitions around the world, her reputation as a feminist painter before her time so secure that like a rock star she is familiarly referred to by her first name only, as in the acclaimed 2020 show at London’s National Gallery, Artemisia, among other recent exhibits.

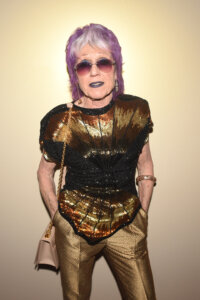

And who honored her several decades before this general rediscovery, in a feminist rediscovery and revival of her own? Yup. Judy Chicago.

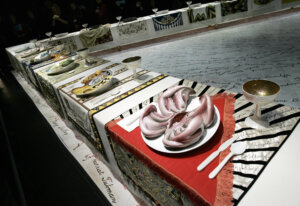

One of Chicago’s best known and most important works is “The Dinner Party,” which since 2007 has been a core holding of the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen) embarked on the mixed media project in 1974 and completed it in 1979.

Her Jewish roots, on her father’s side, includes 23 generations of rabbis, going all the way back to the Vilna Gaon. And anyone who has attended a Seder dinner will note a resemblance between the ritual finery that adorns the traditional Passover meal with this banquet table.

For this dinner party, Chicago has prepared elaborate ornamental and symbolic place settings for 39 women, seated around a majestic triangular — or, thinking of Purim — hamantash-shaped — table. As you greet the women at the table, you will discover the timeline of the history of women, each place setting an artistic treasure in itself, telling each heroine’s tale through the boldly colorful, swirling designs embedded in the ceramic tableware and embroiled textiles.

The women claiming a place at the table constitute an eclectic honor roll of, among others, historical figures from ancient times to the present, mythical goddesses of many cultures, and a bevy of esteemed poets, authors, philosophers, musicians and artists — including, of course, Artemisia Gentileschi.

Gentileschi’s place setting is nestled in a velvet fabric whose golden hue mirrors that of Queen Esther’s gown — a color the artist used in so many paintings it has been dubbed “Artemisia gold.” Beneath that fabric lies a white silk cloth on which the artist’s name has been embroidered in gold-colored thread. The letter “A” is further embellished with a paintbrush and artist’s palette and paintbrush, and a swirling motif of stitched pomegranates — the Mediterranean fruit described in the Bible and that in Jewish tradition symbolizes righteousness — surrounds her name.

Oh, and in case you missed it, a sword is depicted right alongside the palette and paintbrush. It’s a reference to the sword shown in the place setting for another dinner guest, Judith, the bold widowed Biblical heroine who, like Queen Esther, acted to save the Jewish community of her day. And Gentileschi portrayed them both in her own bold way.

This, then, is the distinguished Purim feast I celebrate, in honor of these and all the many other women who have set and enlivened the festive dinner parties that have sustained our lives, and our communities, over generations past, present and future. With a glass of wine in one hand and a poppy seed hamantashen in the other, I toast you all.