The surprisingly gradual but unmistakably dramatic transformation of Mel Brooks

Jeremy Dauber’s ‘Disobedient Jew’ demonstrates why the comic and filmmaker’s work was markedly different in his early years

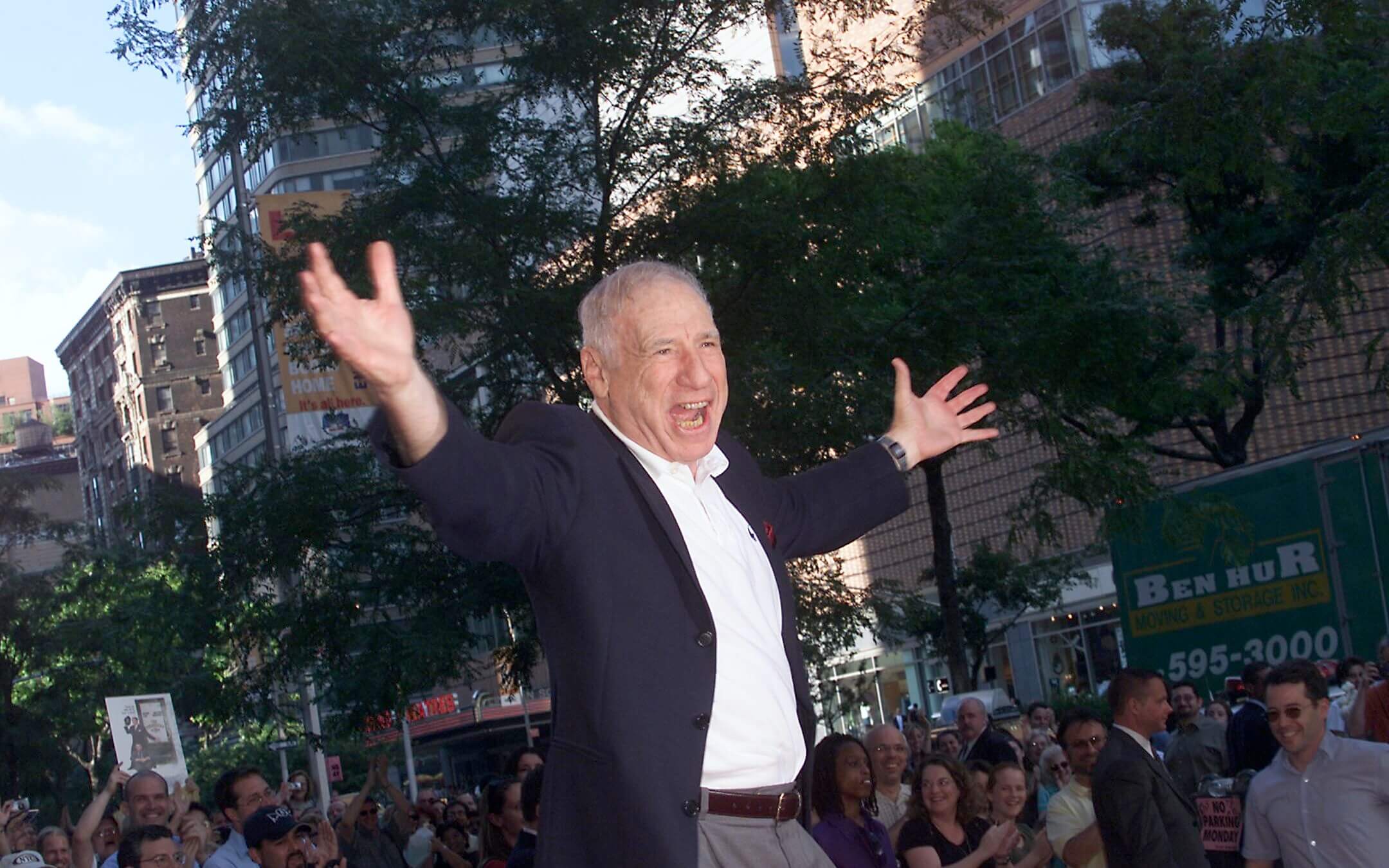

Mel Brooks is the subject of Jeremy Dauber’s Jewish Lives biography ‘Disobedient Jew.’ Photo by Getty Images

Mel Brooks: Disobedient Jew

By Jeremy Dauber

Yale University Press, 216 pages, $26

Some funny people long to be taken seriously, but not Mel Brooks. Of the many fantastically talented, prize-laden Jewish American comics who emerged in the 1950s, he may be the only one who never stopped doing comedy. Woody Allen made his name performing stand-up and guest-hosting The Tonight Show, but by the ’80s he’d traded Charlie Chaplin for Ingmar Bergman and was rewarded with Oscars galore. Mike Nichols got his start in improv but pivoted to Hollywood with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Decades later, he completed his EGOT with the HBO miniseries of Angels in America.

Mel Brooks, who turns 97 this June, began as a jokester and stayed one. He never tried to reinvent himself. Even when he began producing dramas like The Elephant Man, he had his name taken off the credits so as not to confuse audiences — or dim his sparkling persona half a shade.

You can imagine Brooks panicking when he found out the Yale University Press had commissioned a book about him as part of Jewish Lives, a series of short biographical studies that already includes volumes on Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and Moses. It’s hard to explain humor without ruining it, or so the cliché goes, but Brooks needn’t have worried: This is as a good a book as he could have hoped for.

Jeremy Dauber, a professor of Jewish literature at Columbia, has solved the conundrum of writing seriously about comedy. His touch is light throughout. He writes authoritatively about the influence of the Jewish diaspora on postwar American comedy but never forces his points too much. Most blessedly, he doesn’t feel the need to linger on stretches of his subject’s life that he doesn’t find all that interesting (if other writers were so enlightened, the “Biography” section at Barnes & Noble would be several thousand pounds lighter).

We begin in Brooklyn in the 1930s, and even after Brooks departs for Manhattan and Hollywood, we never leave. The childhood of Melvin Kaminsky (like every show business Jew of the era, he changed his name) was a thick stew of stoopball, Universal horror movies, jazz, the Daily Forward, the Marx Brothers, Catskills vacations, cowboy adventures and comic books.

Musicals were semi-sacred — the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers vehicle Swing Time dazzled Brooks when he was a boy, and around this time his uncle took him to see Cole Porter’s Anything Goes, leaving him “infected with the virus of the theater” for life. Decades later, when Brooks was planning his first feature film, a Broadway satire (but one that could only have been concocted by someone with a warm love for Broadway musicals) was the irresistible choice.

The film was, of course, The Producers, and it won Brooks an Oscar for best original screenplay, sending him off on a run of successes that included Young Frankenstein, Blazing Saddles and Silent Movie. If you’re like me and think of Mel Brooks first and foremost as the director of these comedies, it’s easy to forget that his Hollywood phase didn’t begin until he was in his 40s, prior to which he was most famous for co-creating Get Smart and The 2000 Year Old Man.

Dauber is excellent on these early years, when Brooks was a quick-witted and (it must be said) insufferable-sounding kid trying to get ahead — talented, but, as Dauber writes, “constantly wanting.” While performing in the Catskills (which were to postwar American humor, roughly speaking, what quattrocento Florence was to the Renaissance), Brooks befriended Sid Caesar, only a few years older and still at the dawn of his own brilliant career. Caesar’s producer, Max Liebman, couldn’t stand Brooks — even after Caesar began starring in television programs and making a fortune, Liebman claimed there wasn’t enough money to get Brooks a real job.

As it turned out, there was no escape. Out of his own pocket, Caesar paid Brooks $50 a week to hang around the set, and later, when Liebman ran out of excuses, Brooks got work writing jokes for his mentor (alongside Woody Allen, Neil Simon and Carl Reiner). The idea for The Producers had been wafting through Brooks’ sketches for years, and in the early ’60s he tried to turn it into a novel, only to realize that dialogue was pretty much all he could write.

From here, he shopped The Producers as a Broadway play, and, when that, too, failed, as a movie. Nobody in Hollywood expressed interest until Brooks pitched his idea to Sidney Glazier, who found it so funny that coffee squirted out of his nose. Glazier, in turn, couldn’t find anyone interested in financing the film until he met Joseph E. Levine, who later produced The Graduate but at the time was probably best known for bringing Godzilla to American screens. In short, even overnight successes are years in the making.

At some point, a study of Mel Brooks must confront the question comedians get paid to ignore: What does this all mean? Dauber sensibly gets his answer out of the way on the first page of the introduction — Brooks’ humor, and perhaps postwar Jewish humor in general, was defined by a contradictory need “to be loved, accepted, adopted by all; and the irresistible, rebellious urge to take the universal, the standard formula, and to make it funny by making it Jewish.” He was anarchic and nonthreatening at the same time. Implicit in this diagnosis is the point that Brooks got more accepted as he got more successful. His movies got safer and softer-edged.

Maybe that’s our loss. Recently, I watched The Producers for the first time in at least 20 years. I didn’t laugh as much as I did when I watched as a kid (have I ever?), but I’ll say this much: It’s one of the nastiest, most splenetic American comedies of its time — a gleeful attack on … what? Good taste? Gentiles? The Man? Hard to say, exactly, which is part of what’s so great about it — to crib from another great, splenetic American comedian, “So much anger aimed in no particular direction, just sprays and sprays.”

You can feel it in “Springtime for Hitler,” of course, but also in Zero Mostel’s booming, post-blacklist performance, and in the general haphazardness of the filmmaking. There’s not even much warmth between Mostel and Gene Wilder — they’re thick as thieves, true, but only because they’re both thieves.

Compare all this, if you dare, with the musical version of The Producers, which opened in 2001 to rave reviews and record grosses. Lots of the jokes are the same, but where the movie is bitter, the musical is sweet and cuddly: Brooks added a romantic subplot and made the friendship between the two leads the warm, beating heart of the show. What kind of rebellion is this? The contradiction in Brooks’ humor hasn’t resolved itself, exactly, but it’s learned to err on the side of love.

Not that there’s anything wrong with love. Brooks was well within his rights to explore gentler forms of comedy — Dauber basically accepts that his movies got unwatchable after the early ’80s or so, but hey, he’ll always be the director of Blazing Saddles. Still, one wonders what Brooks’ career might have looked like if he’d bitten the hand that fed him. To put him in the ring with his exact contemporary Jerry Lewis (another virtuosic Jewish comic writer-director-performer): In the second half of his career, Brooks never made a self-important train wreck like The Day the Clown Cried, but he never appeared in anything as threatening to mainstream show business — or as self-immolating — as The King of Comedy, either.

Apples to oranges, you say? Maybe, but it’s hard to deny that the musical The Producers (remake-obsessed, character-based, ultimately concerned with Growing Up and Doing The Right Thing) casts a longer shadow over contemporary American comedy than The Producers movie (recklessly original, gag-based, ultimately concerned with pure anarchy).

It’s too bad — funny movies could do with a dose of id like the one Mel Brooks gave it the ’60s. From sea to shining sea, in the name of all that is funny, where are the Catskills of the 21st century?

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.