In this striking portrait of an Ethiopian Jew, she found a surprising connection to her family history

Turns out the background of Kehinde Wiley’s painting was inspired by a 19th centry mizrah

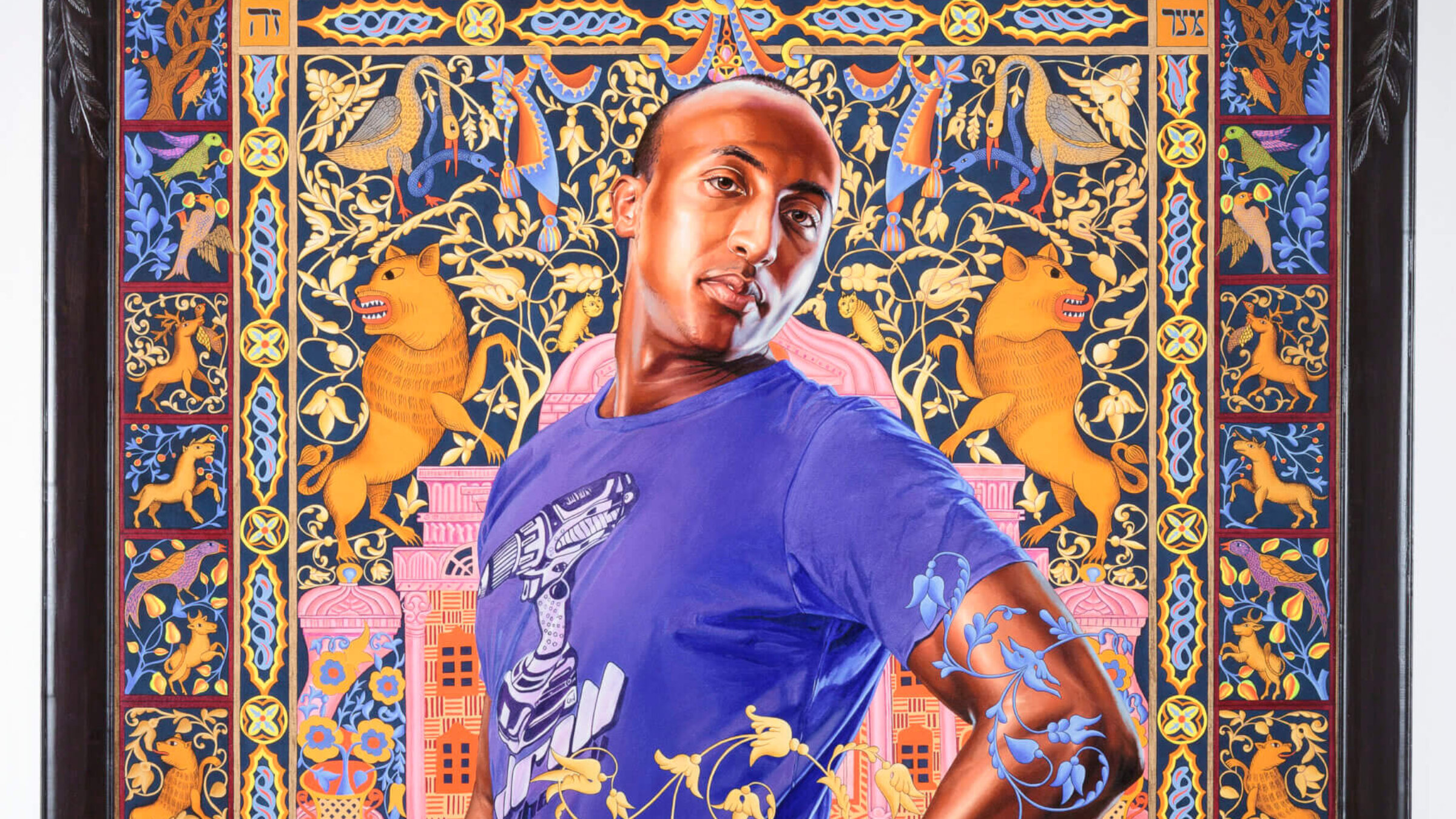

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait depicts Alios Itzhak, a young Jewish Israeli man of Ethiopian descent. Courtesy of The Jewish Museum

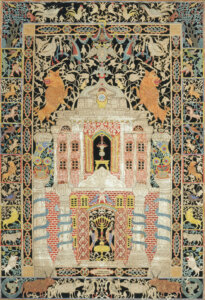

When Amy Shimshon-Santo first saw Kehinde Wiley’s colorful portrait of Alios Itzhak, a young Jewish Israeli man of Ethiopian descent, she couldn’t help but feel that her great-great-grandfather had reached across six generations to shake hands with the artist. That’s because Wiley had chosen her ancestor Israel Dov Rosenbaum’s 1877 mizrah, an ornament or picture hung on an eastern wall, as the background for his vibrant 2011 portrait.

Seeing how Wiley, whose 2017 painting of former President Barack Obama hangs in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, combined Black and Jewish imagery inspired her to learn more. As she dug, she realized there was more to this story than one artist influencing another. It was a story about culture and affirming Blackness and Judaism, and about the complex ways families and communities are connected.

“As an intercultural family we hold so many stories and my challenge as a parent has been to create a space where everyone can feel seen and heard and honored,” Shimshon-Santo told me.

While Shimshon-Santo’s heritage is 99.9% Ashkenazi, her children’s father is from Salvador da Bahia in Brazil. Her children, 28 and 30, are descended from Ashkenazi and African diasporas. Today there are branches of the family in the United States, Israel, Canada, Uruguay and Brazil.

“We raised our kids with the belief that being a family of different heritages inspires the opportunity to learn and know twice as much: 200%, not half. This means honoring our global connections, and practicing the best qualities of Jewishness, Candomble, and Ifa,” Shimshon-Santo wrote in a recent blog post.

It all started last December when Shimshon-Santo’s mother Bruria, a 90-year-old artist, received a box from the Jewish Museum. Tucked among the old calendars and address books, each one emblazoned with Israel’s mizrah, was a copy of the original gift agreement arranged by Rosenbaum’s grandson Sidney with his second wife Helen Finkel.

Her curiosity piqued, Shimshon-Santo started searching on the internet and the name Kehinde Wiley kept popping up next to references to Rosenbaum’s art. Thinking it was a mistake, she cold-called the Jewish Museum.

“The curator confirmed the story. I started crying on the phone. I was so deeply moved. It felt like the ancestors were knocking on my door,” she said.

Dressed in a midnight blue T-shirt, Itzhak stands surrounded by mythical animals and curling vines, some winding across his bare arms like tattoos. “He is one of the many underrepresented and marginalized Black and brown men Wiley painted for his series [The World Stage],” Rebecca Shaykin, associate curator at the Jewish Museum, said.

The exquisitely detailed background is an homage to mizrah, cut paper pieces that were often mounted on the east wall of a synagogue, in the direction of Jerusalem. Looking like something out of a fairy tale, mizrah are rich in symbolic meaning. They often depict the leviathan, portrayed as a curled fish; the wild ox, which was the legendary food of the righteous in the world to come; and the unicorn.

“I just thought it was a beautiful thing. I didn’t know there is a form of art in our lineage that points us to an idea of home. I knew that happens in Islamic tradition with Mecca, which is so cool and then to know that we do that too is awesome,” she said.

That this is a portrait of a Jewish Israeli of Ethiopian descent, painted by a Black artist who drew inspiration from an Ashkenazi Jewish artist whose own descendants are Jews of color, is meaningful, Shaykin said.

“It helps make the art in the gallery more inclusive,” Shaykin said. “Rosenbaum’s mizrah is one of the real highlights of our collection. It’s gorgeous.”

While the mizrah was shown alongside Wiley’s painting in the 2012 exhibit Kehinde Wiley/The World Stage: Israel, and again in the museum’s 2018 Scenes from the Collection, it can’t be permanently displayed because it’s light sensitive. However, visitors to the museum can see an image of it next to Wiley’s portrait.

Shimshon-Santo had the chance to meet Wiley a few months ago at an opening of new works in Los Angeles. After waiting on a long, snaking line, she was able to congratulate him and tell him about the mizrah.

Indeed war and genocide mark her family. Those who couldn’t flee Eastern Europe perished in the Holocaust. Her children’s paternal lines trace to Africa and the slave trade. But that is not how she, or they, define themselves.

“We’re almost 6,000 years old, we wouldn’t have made it through all these challenges and all this time if we didn’t have a lot of these cultural and creative tools for healing and creating. One way we do that is through art and family,” Shimshon-Santo said. “It’s the same thing for the Black side of my family. We’re not defined by slavery. We are an ancient culture that has a lot of ethnic and geographic diversity in it. And that’s a part of our beauty and our strength and we should honor that.”