So, what did Jorge Luis Borges really think of the Jews?

Though he was often called a philosemite, the truth is a lot messier

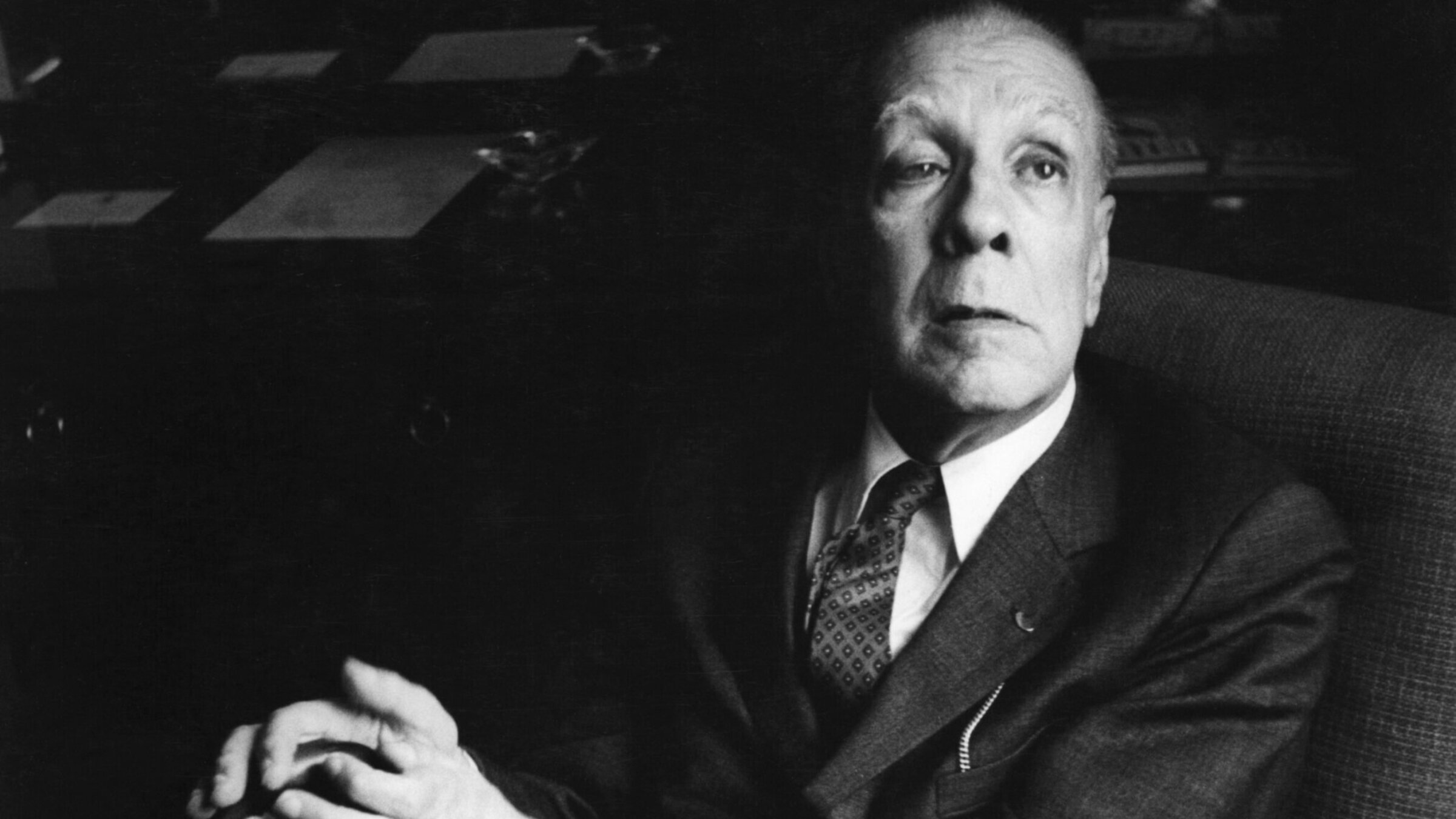

A 1971 portrait of Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges. Photo by Getty Images

When María Kodama, the widow of Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, died March 26, we were moved to reevaluate the writer’s complex, sometimes contradictory attitude towards Jews.

It has become commonplace for critics to praise the philosemitism of such Borges stories as 1945’s “The Aleph,” which was inspired by Kabbalah, describing a point in space that contains all other spaces amid infinite time; and “Emma Zunz,” about a Jewish textile mill worker who murders a Jewish boss, Aaron Loewenthal, who had wronged her father. Among other examples is the 1946 story “Deutsches Requiem” about the crimes of Nazi Germany.

These and further tales and poems have led writers to weightily compare Borges to such Jewish literati as S. Y. Agnon, Walter Benjamin, Franz Kafka, Bruno Schulz, and even Rav Nachman of Breslov. Although from a lapsed Catholic and Protestant family, when barely out of his teens in 1920, Borges was already writing poems inspired by Yiddishkeit, like “Judería” (Jewish Quarter) in which a “Christian mob surges forward, fists full of pogrom.”

In 1934 when accused by an Argentine Fascist group of being a hidden Jew ashamed to admit his origins, Borges responded with an essay, “I, Jew” in which he teasingly referred to his aspiration to be Jewish, spoiled by his languid failure to prove genealogically that his ancestors were Jewish.

Borges’ early vocal opposition to Hitler and Nazism are a matter of record and wholly laudable. The Argentine historian Federico Finchelstein noted that Borges was “one of the first writers to view the Holocaust as part of global history” and “although he never saw a Nazi extermination camp, Borges displayed a firm grasp of the ideological ramifications of the annihilation of European Jewry.”

In old age, Borges visited Israel twice, expressing fervent approval. So where is the ambiguity? Some of the evidence is found in a volume published in 2006 by his friend and literary collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares. At over 1,600 pages, the book, entitled Borges, recounts conversations from meetings or public encounters over four decades, in abundant detail.

Known by aficionados to have been lofty, snobbish, intellectual and reactionary, Borges in unguarded moments turns out to have expressed feelings negating allegiances expressed elsewhere, including about Jews. In 1971, Borges commented to Bioy: “I am not antisemitic, but the fact that everywhere the most varied cultures have persecuted Jews is an argument against [the Jews].”

Yet in the same year, in a public discussion, Borges ranked Jews above other persecuted minorities. When an interlocutor likened antisemitism to homophobia and racism, Borges retorted: “That sentence is unfair to Jews — it places them in bad company.”

Presuming that LGBTQ+ people and African Americans were “bad company,” Borges generally disdained minorities, saying once that he didn’t like Brazil because of the country’s African-descended population. “Their only merit is to have been mistreated and that, as Bernard Shaw remarked, is no merit,” he said.

How did this aspect of Borges’ beliefs remain relatively unexplored for so long, and how should Jewish readers feel about a philosemite who, as it turns out, also indulged in racist and homophobic discourse? The sheer length of Bioy’s book should deter English-language publishers from planning a translation anytime soon, although he voiced similar ideas elsewhere.

Borges’ deserved eminence in later life, along with his blindness after the mid-1950s, and status as a target of Fascist scorn in earlier decades, granted him considerable leeway. But his commitments were always nuanced. He finally approved of Israel, but for some years, mused regretfully about the fact that after 1948, the Jewish state had become a reality instead of remaining mere reverie, which he would have preferred.

Poems written by Borges in homage to Israel are among his weakest. Their militaristic tone sounds perfunctory, as in “Israel, 1969”: “You shall be an Israeli. You shall be a soldier … Only one thing is promised: your place in the battlefield.”

Even in “I, Jew,” Borges remained a sedentary intellectual, preoccupied with daydreaming. Though he was a vibrant reader of Jewish writers from Isaac Babel to Agnon, his energy rarely extended beyond exercising his own literary imagination.

Borges was unlike an early mentor during a stay in Spain, the poet Rafael Cansinos Asséns, who translated Goethe, Shakespeare, and The Arabian Nights into Spanish. Related to the screen goddess Rita Hayworth, Cansinos pioneered Jewish studies in 20th century Spain. On finding his family name in Inquisition archives, Cansinos declared himself Jewish and was circumcised in adulthood.

Nor did Borges follow the active example of another, more sustained influence, his Ukrainian-born Jewish tutor Alberto Gerchunoff, author of the novel Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas. Gerchunoff reportedly toiled with the Austrian Jewish psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to develop a version of the latter’s orgone box, originally intended to concentrate sexual potency, refashioned to preserve Jewish cultural memories.

Despite Borges’ openly expressed libido for aspects of Yiddishkeit, he lacked the will or ardor to pursue this sort of concrete project, however fanciful. Instead, Borges sifted through his fantasies on the printed page. His feelings about Jews and Jewish tradition sometimes lacked coherence. He openly loathed three political, medical and artistic movements largely advanced by Jews: communism (Karl Marx); psychoanalysis (Sigmund Freud); and surrealism (Tristan Tzara).

Borges might have cited a writer he much admired, Walt Whitman, who explained in “Song of Myself”: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself.” Jewish readers of Borges may retain esteem for admirable aspects of his philosemitism and gratitude even for his imperfect friendship, especially in parlous times and contexts.

The key is to recognize Borges’ own priorities, as did Gershom Scholem, the scholar of Jewish mysticism who wisely wrote to the Borges scholar Edna Aizenberg in 1980 that “Borges is a writer of considerable power of imagination and does not claim to represent historical reality, but rather an insight into what the kabbalists might have stood for in his own imagination.”

There is no point in expecting Borges’s works to contain real-life Jews behaving with verisimilitude. Despite his series of friendships with Jewish literary figures, Borges preferred to delve into intellectual and cultural symbols.

Perhaps Borges consciously opted for an aristocratic collage of attitudes about Jews, rather than a cogent viewpoint. Comparably, Kodama, his widow, approved of one French Jew, Prosper Assouline, the Moroccan-born publisher of coffee-table books, including a lavish illustrated tribute to the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Borges.

But in 2006, the French journalist and biographer Pierre Assouline, unrelated to Prosper Assouline but also of Moroccan Jewish origin, wrote about accusations appearing in Spanish language media that Kodama may have “manipulated” Borges’ will to acquire his estate and literary executorship.

Assouline implied that Kodama used this power to eliminate some valid extant translations of her husband’s work, supposedly for extra-literary reasons. Kodama sued Pierre Assouline for defamation and won a partial victory in a French court.

At a certain level of literary renown, loving and disliking different aspects of Jews, like discriminating adamantly between French Jews named Assouline, may just be seen as one prerogative of fame.