Al Jaffee’s MAD Magazine was my personal Talmud

The late comic artist continued a grand Jewish tradition of questioning

Al Jaffee in his studio in 2016. Photo by Marissa Scheinfeld

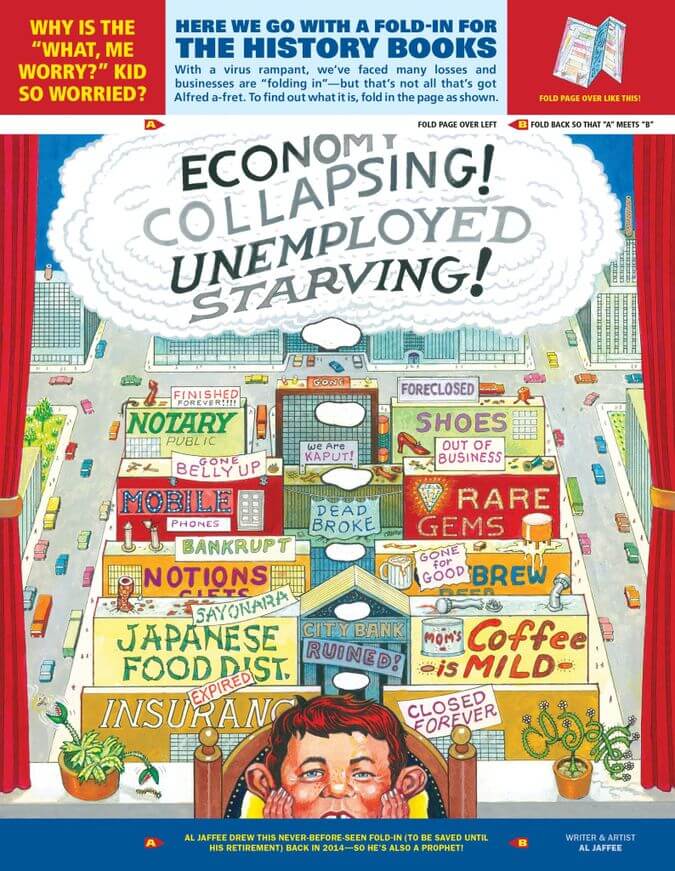

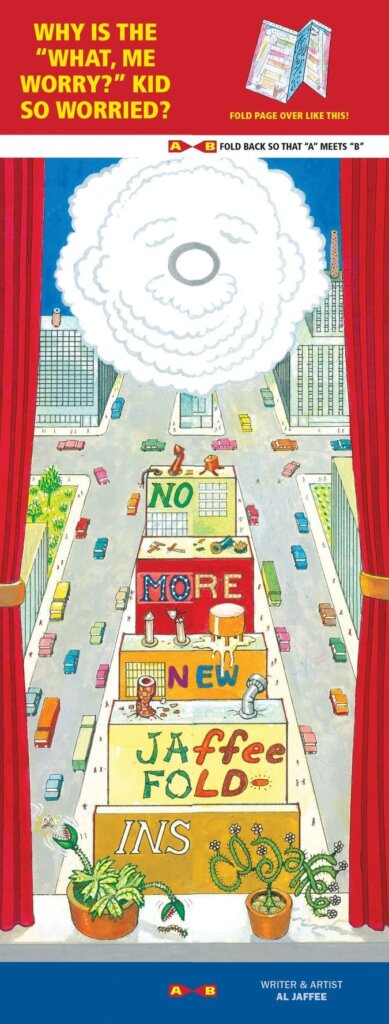

In my secular Jewish upbringing, a MAD Magazine fold-in — the issue-ending cartoon editorial that transformed when folded along arrows labeled A and B to a terse punchline — was as close as I got to reading a page of Talmud.

Every month for years, beginning with issues sent in care packages to my sleepaway camp, I’d read through the magazine cover to cover. But I savored the back page, where Al Jaffee, the longest-tenured MAD employee — and, per Guinness World Records, the comic artist with the longest career, period — supplied an artful social commentary.

I often tried to figure out what Jaffee was saying before I creased the page, a challenge that would, I thought, prove not just the strength of my intuition, but also that my worldview accorded with his own savvy, sardonic and adult one — that was, nonetheless, deeply skeptical of the world adults built.

From the edges of the page, which provided a typically busy, detailed landscape, I could almost make out the image that would form when the page met in the center — the hints of a design that answered a question.

A classic example, from 1968, showed young people gathered around a career center, posing the query,“What is the one thing most school dropouts are sure to become?” When folded at the center, fences along both sides of a path came together to form a cannon, with a young man’s face inside. The unfolded text collapsed into a two-word answer: “cannon fodder.” (One from my own time as a reader asked, “What was President Bush most upset to see destroyed by Hurricane Katrina?” Answer: “His approval rating.”)

It felt Talmudic not just because the Talmud is arranged with the Mishnah and Gemara in the center, with commentaries flanking it, but because it seemed to hold some deep knowledge. If the fold-ins were, unlike the Talmud, short of dialectic, my own engagement — my guesses, my close reading of what a cloud or hill might form when folded over, or where the letters might overlap — made them an invitation to think deeper, to arrive at an essential peshat about celebrities, the economy or the Alfred E. Neuman of presidents.

Jaffee, who died Monday in Manhattan at the age of 102, was uniquely suited for MAD’s long run of anti-establishment, furshlugginer humor — furshlugginer being just one of the faux-Yiddish words peppered throughout the magazine’s pages. He was born in Savannah, Georgia, but when he was 6, his mother, an immigrant, moved him and his siblings back to her Lithuanian shtetl.

There, he learned to speak fluent Yiddish, and to cut down authority figures with comedy.

“Your only revenge is to expose and make fun of the frailties of the big shots and the ‘better-than-thou’ people,” Jaffee told Leah Garrett for a 2016 profile in the Forward. “We made fun of our rabbis. Some of it was a bit raw and mean spirited, especially the comments about the personal habits of the rabbi when he went to the outhouse and defecated all over the board.”

“Going after the wealthy is such a release when you are barely getting by,” he added.

That was the start of what Jaffee would one day call his brand of “anti-adultism,” a concept he kept with him into his 11th decade.

In the George W. Bush era, when I first started reading, MAD’s writing staff, referred to as the “usual gang of idiots,” became victims of their own success. They had influenced generations to kick at the knees of politicians, admen and Hollywood with gleeful elan, to the point where they no longer stood out amid the creative output their sensibility inspired.

It’s almost impossible to imagine a world with The Daily Show or The Simpsons without MAD. That influence was broadly acknowledged, up to and including through a famous visit by one Bart Simpson to the MAD offices and a fold-in cake from Stephen Colbert.

Jaffee was the one remaining contributor from the founding generation, an establishment figure who continued to take on the man as a senior statesman until his retirement in 2020, months after the magazine stopped publishing a monthly issue.

For me, Jaffee meant consistency. In college I wasn’t always intimately familiar with what parodies graced the covers of MAD — a Twilight sequel, Adventure Time — but I could always count on Jaffee to deliver a topical grace note. (And, if I really wanted to break my brain, I’d try to do a mental fold-in at a Hudson News store — you crease it, you buy it.)

As the roster at MAD changed through the years, with folks who grew up reading it graduating to the masthead, Jaffee was also a reminder of its Jewish, Yiddish-inflected beginnings, which may well have spelled the key to his genius. Did leaping between Yiddish and English, one read left to right, the other right to left, help Jaffee develop that particular genius for perspective — the unique way in which a page can behave and a text be transformed?

“I tend to think in Yiddish, and Yiddish conveys humor better than English,” Jaffee told Garrett.

Jaffee’s fold-ins, which irreverently inverted the mechanism of centerfolds, were just one side of his brilliance. Perhaps even more in the Jewish tradition were his “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions,” in which a woman might be pictured entering an optometrist’s office and asked if she’d like her eyes examined.

Among her options for sharp-tongued retorts: “No, I’d like a pound of chopped liver, I get my eyes examined at the delicatessen.”

These retorts are as Jewish as “who am I, my brother’s keeper,” the non-answers to the four questions at Passover, Abraham’s challenges to God — and even a dirt-floor cheder in Lithuania, where a young Abraham Jaffee (later Al) sparred with the rabbis.

Maybe that’s why wrestling with Jaffee’s fold-ins in a camp bunk, my first summer from home, I felt as if I was realizing a birthright. To fold that page over, to reveal its hidden insight, was one of the most Jewish things you could do — and I think Jaffee knew that.