On Paul Simon’s dark night of the soul, he wants it darker — much darker

The 81-year-old artist’s latest album, ‘Seven Psalms,’ confronts mortality with honesty and just a bit of humor

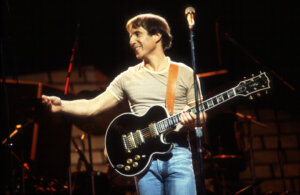

Paul Simon performs at Royal Albert Hall in London,. 2016. Photo by Getty Images

During the darkest days of 2020, with COVID-19 running rampant and a significant portion of the U.S. population deciding that the freedom to infect and be infected was of paramount importance to their personal Bill of Rights, one Paul Simon lyric kept going through my head:

I have my books

And my poetry to protect me

I’d always loved that line from Simon and Garfunkel’s 1965 hit “I Am a Rock,” and how it somehow managed to feel earnest and ironic at the same time. Sung from the point of view of a misanthropic recluse living under self-imposed lockdown, the song is both a fierce rejoinder to John Donne’s “Meditation XVII” (“No man is an island, entire of itself …”) and a succinctly evocative character study of a damaged and defensive individual. Maybe the self-proclaimed “Rock” truly believes what he’s saying, but more than likely he knows deep down that it’s all a front, and that his books and poetry and his “fortress deep and mighty” will ultimately do little to shield him from the pain and fear of human existence.

Still, there were times back in 2020 where I saw the definite appeal of hunkering down with my books and records and headphones while sickness and craziness raged outside my walls. Maybe they wouldn’t offer much of a defense in the long term, but they could at least temporarily stave off the existential dread, as well as give my desk a much-needed respite from the frustrated pounding of my cranium.

But as Paul Simon’s new Seven Psalms acknowledges, all lines of defense — be they books and poetry, or internet outrage and outright denial — are ultimately temporary, and ultimately useless. A 33-minute meditation on mortality and what may or may not lie beyond it, Seven Psalms finds the 81 year-old singer-songwriter trying to look his own impending exit as squarely in the eye as possible.

Seven Psalms is a fascinating, haunting, and often deeply moving piece of work, a dark night of the soul distilled into one unbroken track of seven movements — or more, if you count the several reprises of “The Lord,” the album’s opening track. Centered around Simon’s hushed vocals and deftly picked acoustic guitar, the lyrics of “The Lord” dive right into the deep end. “I’ve been thinking about the great migration,” he sings in its very first line, “Noon and night they leave the flock.” The song looks in wonder at the beauty of existence, while also marveling at the impermanence of it all. “Nothing dies of too much love,” he sings, but then there’s no amount of love that can confer immortality, either.

Simon sees the hand of God in terrible and troubling things, as well. “The COVID virus is the Lord” may be one of the least elegant lines that Simon has ever written, but he returns to it again and again in “The Lord” and its reprises, as if to underscore how the pandemic marked a turning point in his understanding of human existence.

Also repeating throughout the song is a guitar figure suspiciously similar to “Anji,” the fingerstyle instrumental written by British guitarist Davey Graham that became a standard on the UK folk scene of the early 1960s. Simon learned the song in England during his solo sojourn there following the recording of Simon & Garfunkel’s folky 1964 debut Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., and recorded it for the duo’s hit 1966 follow-up The Sounds of Silence; the reappearance here of its main lick seems alternately like a fond talisman from his carefree younger days and a compulsive tick, like the fingering of prayer beads in times of great stress and uncertainty.

Simon’s wife Edie Brickell appears on the final two songs, “The Sacred Harp” and “Wait,” and there are subtle cameos throughout from guests including trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, the vocal ensemble Voces8 and various chamber musicians, but the album never really breaks from its downbeat mood and atmosphere. Which is not to say that there isn’t some humor here. “My Professional Opinion” playfully (if also mournfully) skewers our current culture of grievance and the 24-7/365 Festivus celebration raging on the internet:

Good morning, Mr. Indignation

Seems you haven’t slept all night

In my professional opinion

Go back to bed and turn off your light

Our time is short, Simon is telling us, so why are we wasting it arguing with strangers on social media? Better to get on with the business of living — and of dying, which is unfortunately part of the deal whether we accept it or not. “We’re all walking down the same road to wherever it ends,” Simon sings in “Trail of Volcanoes.” “The pity is the damage that’s done leaves so little time for amends.”

But what does dying even mean? Is there a Heaven or a Hell? Or just silent nothingness? And how tightly should you cling to your faith — or how freely should you let your doubts roam — as the end approaches? “I want to believe in a seamless transition,” he sings in “Wait,” “I don’t want to be near my dark intuition.”

This all adds up to what sounds very much like the final musical missive from an iconic artist. It’s entirely possible that Simon has many more good years ahead of him, with even more music to come. But if not, Seven Psalms (his first album of new material since 2016’s Stranger to Stranger) will stand as a remarkable farewell, a thought-provoking, deeply personal look into the abyss that stands right up there with David Bowie’s Blackstar and Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker. If you’ve ever been a fan of Paul Simon in any of his many musical incarnations, Seven Psalms is definitely a record you need to hear.