Jewish writers not only inspired Martin Amis — they made him want to become part of the family

Enamored of Roth, Mailer and Singer, the English writer viewed Saul Bellow as a sort of father figure

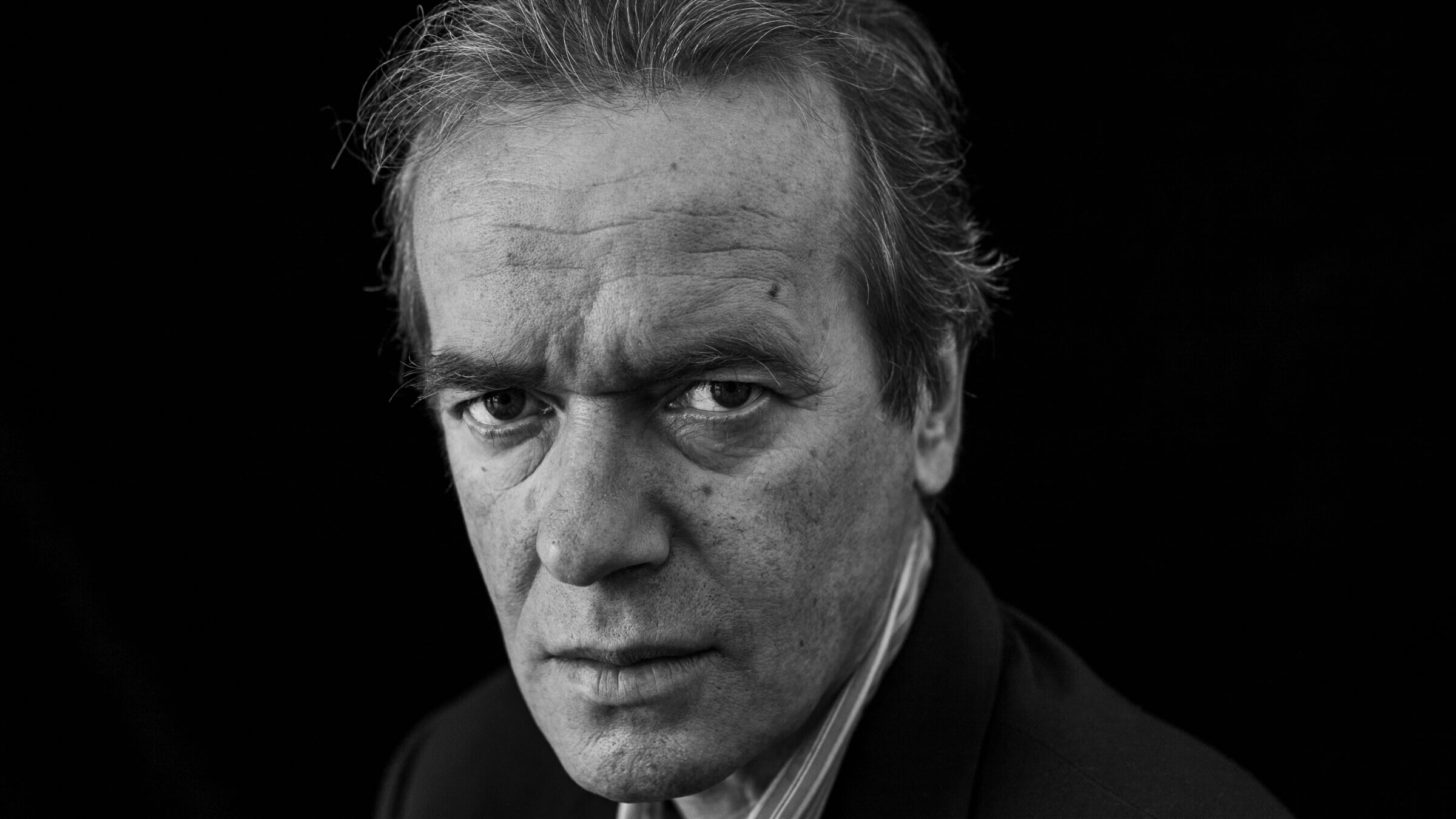

Martin Amis, circa 2007. Photo by Getty Images

The English novelist Martin Amis, who died May 19 at age 73, looked to America as a promised land for literary achievement, and to U.S. Jewish writers as inspirational overachievers.

In his essays, even when praising the non-Jewish John Updike, Amis did so because Updike “alone could hold his head up with the great Jews — Bellow, Roth, Mailer, Singer — it was entirely typical of him that, as a sideline, he became a great Jewish novelist too, in the person of Henry Bech, the hero of several of his books.”

Amis embraced the notion that by inventing Jewish characters, a writer might indirectly attain Yiddishkeit. Indeed, Amis clearly identified with Updike’s supposed claim that “by developing a Jewish persona [he] was saying something like: ‘Look, I’m really Jewish too. We’re all Jewish here.’”

So unlike non-Jewish writers of an earlier generation like Capote or Vidal who reacted to Jewish achievement in American literature with antisemitic sarcasm, Updike (and by extension Amis) decided to assimilate with the Jews.

Amis admired Jewish success in all creative domains; he was moved by Steven Spielberg’s E.T., especially its box office receipts. After noting the earnings of Spielberg’s films in one 1982 essay, Amis added with quintessential unabashed careerism that Spielberg was “34, and well on his way to becoming the most effective popular artist of all time.”

“What’s he got?” he asked. “How do you do it? Can I have some?”

Already celebrated for rambunctious, profane satires, Amis also produced two novels about the Holocaust: Time’s Arrow (1991) and The Zone of Interest (2014).

Both received mixed critical receptions. Cynthia Ozick dissed The Zone of Interest, musing that Amis interpreted a citation from Primo Levi about concentration camps being impossible to understand as carte blanche to charge in and address the subject in his typically rollicking, raucous manner.

Aptly using the jazz term “riff” to evoke Amis’ verbal derring-do, Ozick concluded that his “fractious” novel’s existence was useful because its existence “makes the best argument against itself.”

Equally paradoxically, in 2012 Amis told Ron Rosenbaum that soon, the “Holocaust is going to absent itself from living memory” and the absence of any survivors with direct experience of the historical suffering emboldened him to express himself on the subject.

As further justification, Amis offered what he presented as a quote from the German author W.G. Sebald that “no serious person ever thinks about anything else” than the Holocaust. Oddly, this extreme view does not appear to be anywhere in Sebald’s published writings or interviews. Yet Amis repeated it in fictionalized memoirs and on public occasions until the quote became Amis’ own.

To further justify his monomania about the Holocaust and his own interpretive role in it, Amis added a note to The Zone of Interest about his preparatory reading, including books by the American Jewish psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, Martin Gilbert, Gitta Sereny, Joachim Fest, Arno Mayer, Erich Fromm, Simon Wiesenthal, Henry Orenstein, Nora Waln and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Ever ambitious to compete with these eminences, Amis clearly diverted such elders as Saul Bellow, whom he went beyond merely revering, to the point of coopting into his personal mispochech.

When Amis’ father, the noted author Kingsley Amis, died, the younger Amis phoned Bellow to announce that now paternal identity was transferred onto Bellow, who already had four children of his own (“My father died at noon today,” he said. “So I’m afraid you’ll have to take over now”).

In later published reminiscences, Amis recalled peppering Bellow with questions related to Yiddishkeit, such as why Jewish writers are not alcoholics, a notion that reveals surprising ignorance of such shikkers (drunks) as Joseph Roth, Arthur Koestler and Dorothy Parker among others.

There was a characteristic element of flippancy in Amis’ self-defined philosemitism. His father Kingsley Amis portrayed antisemitism in the controversial novel Stanley and the Women and in private correspondence with friends who were either like-minded or whom he wished to shock for amusement’s sake.

Yet Amis grilled his father on the topic, and recounts in an autobiography that he recited to him an excerpt from Primo Levi’s If This is a Man describing Jews on the eve of deportation from Italy; the elder Amis wept, saying that the Holocaust should never happen again.

This father-son scene, cited in a book-length tribute to Etty Hillesum, a Dutch Jewish writer who was murdered at Auschwitz, shows that Amis saw education as a personal mission. Yet in an overview of antisemitism in England, historian Anthony Julius had a more nuanced and semi-tolerant view of Stanley and the Women than the author’s own judgmental son.

When not adopting Bellow as a substitute father, Amis also championed Philip Roth, writing in 2018 that kvetching about the portrayal of Jews in such books as Portnoy’s Complaint was “essentially socio-cultural, and not literary. You can understand the historical uneasiness, but World Jewry got it wrong about Roth, a proud Jew as well as a proud American.”

Even with the combative Norman Mailer, Amis found affinities, as he admitted to Haaretz in 2019, praising Mailer’s reflections on fiction writing in the book-length essay The Spooky Art while disavowing other aspects of Mailer’s behavior.

Taking these Jewish writers personally was natural for Amis whose second wife, as journalists repeatedly pointed out, is Jewish; he flippantly referred in household conversation to their two daughters as “the Jews.” Even Amis’ lifelong friend, the polemicist Christopher Hitchens, announced that in 1987 he belatedly learned about his own Judaism.

Yet despite these doubtless genuine emotional motivations, Amis’ choice to amplify bad feelings by anti-Muslim statements following the Sept. 11 attacks and subsequent terrorist threats were of doubtful utility. Especially his suggestion that all Muslims, including the 95% who had no radical or terrorist sympathies, should “suffer” because of their errant brethren, offended many observers.

Less Swiftian, but also questionable, were Amis’ assertions to a fawning Israeli reporter in 2019 that “there’s no place for being sweet, especially not in the Middle East” and therefore “Israel just had to become a tough guy.”

To bolster his contention, Amis cited a 17th century poem written by Andrew Marvell, “An Horatian Ode upon [Oliver] Cromwell’s Return from Ireland,” in praise of an English leader after a military expedition to Ireland.

Juxtaposed with this elegy to carnage, Amis offered a Mailer-like paean of praise to sabra machismo: “Israel just can’t afford to be a sweetie, it had to learn the art of violence.” He even quoted Bellow that “Jewish manhood would have been dead without Israel,” as if the Jewish state were merely a Mediterranean version of Viagra or Cialis.

This unproductive, reductive stance should not distract from Amis’ undisputable devotion to American Jewish achievements in the arts, especially literature, which he fervently modeled his own storied career after.