How one man’s photographic memory helped preserve the music of the Nazi camps

Aleksander Kulisiewicz survived Sachsenhausen and went on to create a jaw-dropping archive

Aleksander Kulisiewicz was a Polish gentile and amateur musician who devoted his postwar life to preserving the songs and poetry of the camps. Courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

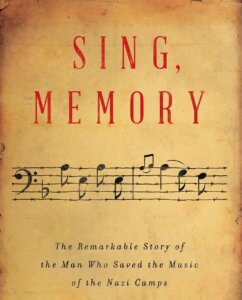

Sing, Memory: The Remarkable Story of the Man Who Saved the Music of the Nazi Camps

By Makana Eyre

W.W. Norton & Company, 352 pages, $32.50

In the hellscape of Nazi concentration camps, music was an instrument of both torment and resistance. The grisly image of an inmate orchestra at Auschwitz-Birkenau playing Jewish prisoners to their deaths is part of this complicated history. So, too, are tales of inmates whose musical gifts earned SS favor.

Makana Eyre’s Sing, Memory tells a different story — at once improbable, inspiring and deeply sad.

Its principal protagonist is Aleksander Kulisiewicz, a Polish gentile and amateur musician who devoted his postwar life to preserving the songs and poetry of the camps. Imprisoned for his anti-Nazi writings, Kulisiewicz spent five years in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, outside Berlin. There he befriended a charismatic Polish Jewish choir conductor, Rosebery d’Arguto, whose career in Berlin had been derailed by the Third Reich.

Under unimaginably difficult conditions, d’Arguto formed a secret Jewish choir that performed at Sachsenhausen. He and other prisoners, including Kulisiewicz, also composed wrenching, bitter songs about their ordeals — sardonic parodies of popular tunes, hymns, dirges, elegies, even a lullaby for a murdered child.

These tokens of both consolation and resistance would likely have vanished into obscurity had it not been for Kulisiewicz and his uncanny memory. Perhaps owing to a childhood accident, Kulisiewicz had a photographic recall that allowed him to precisely retain musical scores, poetry and other compositions. After the war, he reached out to survivors of other camps, and he made documenting and performing their work his mission, to the detriment of his own health and family life.

Kulisiewicz’s voluminous archive ultimately found a home at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, where it became a major source for Sing, Memory. Eyre also was able to interview Kulisiewicz’s three sons, as well as two of d’Arguto’s relatives (including his late nephew, the Holocaust rescuer and memoirist Justus Rosenberg). With rare immediacy, and despite some repetitiveness, Eyre’s narrative captures the poignancy of Kulisiewicz’s life story.

The book begins with his childhood and young adulthood in Cieszyn, Poland, and nearby Kraków. A musical prodigy, Kulisiewicz was drawn to the spotlight. Among other gifts, he was an adept whistler, and his early stage appearances were crowd pleasers.

Endowed with “talent, burning ambition, and just enough privilege,” he was able to enjoy the relatively cosmopolitan Poland of the 1930s. Under pressure from his father, he studied law. He also dabbled in right-wing Polish nationalism and succumbed, for a time, to the antisemitic prejudices of his era.

The 1939 Nazi invasion of Poland interrupted that trajectory. Kulisiewicz’s modest resistance activities landed him in prison and then Sachsenhausen, where his robust youth, fluency in German and Czech, and knack for forging alliances, helped him overcome beatings, harsh work assignments and starvation rations.

After a chance meeting, he formed an intense musical bond with d’Arguto. Eyre idealizes both the conductor and the friendship between the two men. “In Rosebery, [Kulisiewicz] saw generosity, a deep caring for the people around him, and an unfettered commitment to music,” Eyre writes. “Rosebery remained true to himself,” and, when he conducted, he “seemed a mythical figure” with “an almost supernatural quality.”

Sing, Memory recreates the daily humiliations and hardships of Sachsenhausen in riveting detail. Among them was the SS torture known as “sport,” in which exhausted and starving inmates were required to perform pointless physical activities deep into the night. The SS also forced inmates to sing German songs, punishing them if they faltered or failed to know the words.

While music could be a weapon at Sachsenhausen, it also served as a comfort, an assertion of humanity and a means of resistance. Composing caustic lyrics helped distract Kulisiewicz from physical pain. Memorizing the works of others gave him a purpose beyond himself, stiffening his will to survive. Among the musical numbers he preserved were d’Arguto’s elegiac “Jewish Deathsong,” memorializing prisoners aware they were “bound for the gas,” and a father’s lullaby for his murdered son, consigned to a “crematorium black and silent.” At Sachsenhausen alone, there were dozens more.

“Over time,” Eyre writes, “it felt as though an octopus of camp culture undulated within him, ever expanding as the hatred and harm and the most intimate longings of so many prisoners filled his being.”

After some close calls, including temporary blindness from a dog virus and the rigors of a death march, Kulisiewicz — unlike nearly all the camp’s Jewish inmates — survived. But his later years were often rocky.

He toggled between Czechoslovakia and Poland, working as a reporter and refusing to join the Communist Party. He married twice, but neglected both wives, as well as his three sons, and ended up twice divorced and lonely. His physical and mental health both deteriorated. Trauma from the camp lingered, plunging him into depression, keeping him “locked in Sachsenhausen forever.”

Against the odds, he obsessively built his archive. He also traveled across Europe (even to Germany) and eventually to the United States to perform camp songs. A comprehensive book he wrote on the music of the camps remained unpublished. But, with American support, he was able to record a multilingual 1979 album, Songs from the Depths of Hell.

Kulisiewicz was not an easy man, Eyre makes clear. “Being a good husband or father was not his calling,” he writes. “On his best days, he was demanding. On a bad day, he was contentious, brawling, ready to explode if he felt offended.”

In the end, Sing, Memory is a tale of hardship and decline but also of triumph, however costly. In his performances of camp music, Kulisiewicz, while embodying torment, was also most authentically himself. “I’m paying back a debt of memory to millions of my murdered fellow prisoners,” he said at one point. “They are always with me.” And now, through their searing words and melodies, with us as well.