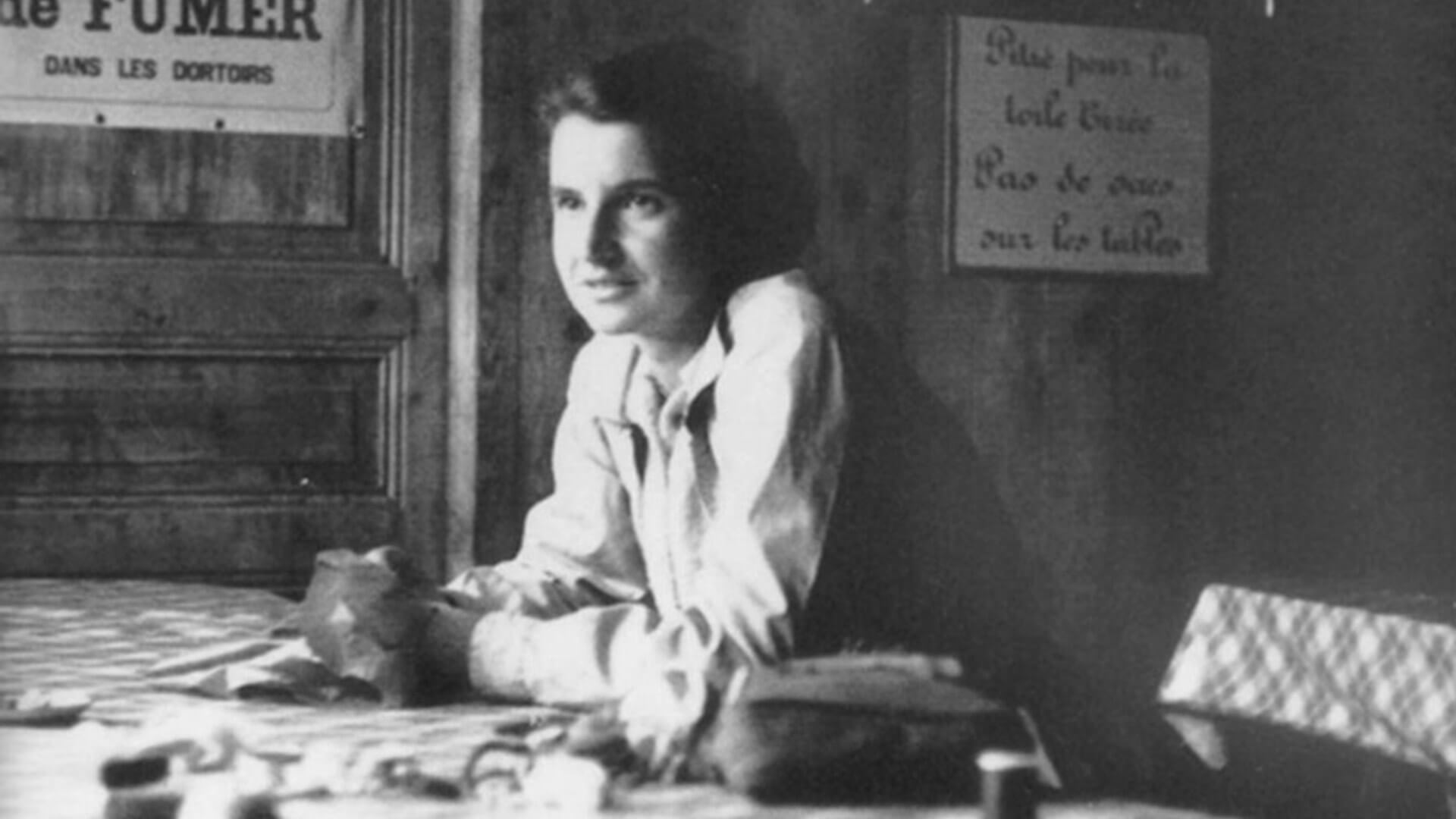

A neglected Jewish pioneer is having her say — this time in a musical

‘Double Helix’ tells the story of Rosalind Franklin, DNA and life itself

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Seventy years ago, James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of life itself in the double helix of DNA — but they didn’t get there alone.

Watson and Crick, whose breakthrough earned them the 1962 Nobel Prize, couldn’t have done it without Rosalind Franklin, a brilliant, headstrong X-ray crystallographer at King’s College, whose DNA photograph suggested the structure.

In recent years, placing Franklin back in the story has been a bustling business, with biographies, a play starring Nicole Kidman and even an eponymous Mars rover. Since 2018, composer Madeline Myers and her collaborator, actor Samantha Massell, have been setting her life to music.

The musical Double Helix, which makes its world premiere May 30 at Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor, New York, is yet another spin on a tale that’s been contested for decades in various memoirs, but never Franklin’s own. Myers and Massell aren’t just hoping to give Franklin the credit she deserves — they want to rescue her from narratives eager to claim her as a trailblazer but unwilling to see as much more than a symbol.

“Rosalind Franklin’s narrative has become this woman who is a victim and who has been scorned and who has become this kind of feminist icon,” said Myers. “And Rosalind Franklin wasn’t a feminist. She wasn’t fighting institutional sexism in her workplace. She was a scientist and she had not seen data that suggested that women should be treated any differently from men. That was her worldview and that’s why she was advocating for what she was doing.”

Myers, whose other work includes Masterpiece, about a notorious art heist, and Flatbush Avenue, about women fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers, heard about the race to discover the structure DNA in the late 2010s. Having no background in science (“the lowest grade I made in high school”), she dove headfirst into researching Franklin’s life, even having lunch with one of Franklin’s brothers, then in his 90s.

In 2018, Myers was in Denmark to premiere a suite of her music. Massell, who played Hodel in the 2017 Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof, met up with her in Copenhagen for a hiking trip in the Faroe Islands. Myers pitched Franklin’s story, and promised Massell the role. Both women connected with Franklin’s energy — and not just because she was also an avid hiker.

“She had a lot of chutzpah and she was very ambitious and she was tenacious,” said Massell, during a lunch break at Double Helix’s midtown Manhattan rehearsal space. “I see so much of that in me. I see the good elements and the bad elements, because it ends up being a huge emotional undoing for her.”

In working on the show for years — through workshops and pandemic-era virtual performances — Myers and Massell have become unofficial Franklin authorities.

In rehearsals, Myers helped to block a scene, noting how Watson remembered a tense encounter with Franklin in his memoir. When director Scott Schwartz asked the actor playing Francis Crick to be less confrontational with Rosalind, Massell noted how Franklin and Crick actually had a good relationship. She stayed with him when she was sick with ovarian cancer, of which she died in 1958 at the age of 37.

One aspect of Franklin that grew with each revision was her Jewishness. Watson, who is still alive and, as late as 2007, told a reporter “some antisemitism is justified,” is the source of much of the play’s antisemitism. Franklin’s own relationship to her Jewishness at first seemed incidental, though her family was involved in Jewish charities. She identified as a scientist first.

But Myers, who, like Massell, is Jewish, concluded that Rosalind’s constant questioning and her need to debate — often in a way that creates friction with Anglican colleagues — made her a very Jewish character. Franklin’s lover, Jacques Mering, a Russian-Jewish refugee, and her mentor, Adrienne Weill, a Jewish refugee from France, also add to the Jewish ethos of the play, insisting that Rosalind be grateful for her life. (Myers says Weill’s solo, “If You’re Lucky,” is inspired by the Mourner’s Kaddish.)

“I stumbled on this idea that maybe actually it’s her Jewishness that pushed her into this all along,” Myers said of Franklin’s desire to study the building blocks of life. “Judaism is so focused on the here and the now, it’s about life! It’s about living.”

The musical, which Forward intern Rebecca Salzhauer is working on as part of the directing team, is mostly sung-through with Sondheimian arias and a score influenced by modern and late-Romantic composers. It ends with Franklin taking stock of her life on the edge of death. It also invites audiences to consider how antisemitism and misogyny are still with us, right as faith in science is disappearing.

“There’s a repeated theme in the show: science tells the truth,” Massell said. “We’ve been living in this pandemic not just of disease but also alternative facts and misinformation, and Rosalind is always striving for the truth.”

Tickets and more information about Double Helix can be found here.