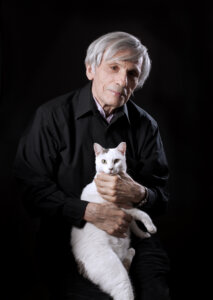

Fiction excerpt: The Baron of East Broadway, by Jerome Charyn

On the Lower East Side, Ab Cahan is once again the Pulitzer of Yiddish Land, the William Randolph Hearst of the Jewish ghetto

For Ab Cahan, the Forward building was his personal colossus. Courtesy of Forward Association

Editor’s note: The following story is excerpt from Jerome Charyn’s Ravage & Son, a novel to be published by Bellevue Literary Press in August.

He was called the Pulitzer of Yiddish Land, the Ghetto’s William Randolph Hearst. Cahan had a colossus — the Jewish Daily Forward. It had more readers than the Philadelphia Inquirer and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and it was published for a population of immigrant Jews. Cahan liked to boast of his million readers, since entire families devoured each issue of the Forward, not only on the mean streets surrounding East Broadway, but in Buenos Aires or Budapest and all the other world capitals where the paper was sold in 1913. But Cahan could taste the bile on his tongue as he looked into the heart of the Lower East Side from his lair on the tenth floor of the Forward building, as his operators next door composed the current issue with the hot metal slugs of their typesetting machines.

There was a swirl of red dust outside and a din that had nothing to do with his compositors. The dust was no mystery to Abraham Cahan; it was bits of rubble and red chalk that flew off the walls and ragged roof lines of the tenements and other buildings, as if some monstrous sculptor was chipping away at every piece of property in the Ghetto: schools, synagogues, churches, the Ludlow Street jail, the Essex Market Court, the pushcarts, the pylons of the Williamsburg Bridge, the earth that was dug out of Delancey Street for a new subway line, the flanks of dray horses that attracted flies and more dust — the mischievous sculptor was time itself. And time was the great enemy of a Yiddish editor. Cahan could only prosper if new immigrants scrambled off the boat from Ellis Island with their baggage, their children, and their wives. One day soon this immigration would come to a halt, and the Forward’s readers would disappear into the red dust.

He’d rescued the paper out of bankruptcy and oblivion. Circulation leapt like a wild storm on the Lower East Side when he introduced A Bintel Brief (A Bundle of Letters), in 1906. He had to steal from other Yiddish papers and from Hearst. A Bintel Brief was a lonely hearts column, but with Cahan’s particular twist. He would receive letters from his readers — most of them garbled and illiterate — would revise them with a stroke here and there, so that the letters sang their tales of woe and grief.

He was always revising and answering some Bintel Brief. Men wrote to him as well as women, but Cahan knew that he had captured every second housewife on the Lower East Side as a willing slave to his column. Sometimes he had to disguise the writer of a Brief, or he would have caused a scandal and heaped shame upon the heads of his own contributors. So he juggled names, addresses, like a Jewish acrobat. Was Sonya of Sheriff Street planning to run away with her star boarder and abandon a pair of little girls and a renegade husband, who was drunk half the time and beat her black and blue? “I love our boarder,” she confessed. “He doesn’t have clumsy hands. He never pinches me. He writes poems while he’s at the shop. He loves my daughters. We’ll run to Canada, I swear to God.”

Cahan had touched some primitive cord. Adultery was a common enough theme in the Ghetto, where wives, husbands, and boarders were packed into tenements, rushed half-naked in and out of some toilet in a darkened hall. Didn’t Cahan publish feuilletons that were fatalistic about love. He could admire the Master, pour over Henry James like a rabbinical scholar, sniff the perfume of every paragraph, but he himself was a creature with crippled wings. His novelist’s craft was entombed in the pages of the Forward, almost every word of which he wrote or revised. And he seldom had any peace from his sub-editors.

While he was glancing out the window, Barush, his managing editor, marched in, clutching some copy, wound into a scroll, like a satanic Torah in bleeding black ink. Barush wore a pince-nez, the same as Cahan’s wife. He’d once been Cahan’s boss, on another Yiddish paper. He was a drama critic, a playwright, and a novelist whose feuilletons appeared in the Forward, but no housewife or tailor could have untangled his high-toned Yiddish.

Cahan knew Barush’s little tricks. All his sub-editors were novelists and poets. He published their work as often as he could, but they longed for much more than an editorial or a feuilleton in the Forward.

“Barush, we’ll run your feuilleton on the Polish riders next week.”

Barush was silent for a moment; he had his own wolf-like cunning. “Did you like it, Comrade?”

Cahan hadn’t read a word of the feuilleton.

“I adored it,” he said.

“And on what page will it appear, Comrade Editor?”

“You can have the sixth page all to yourself — with an illustration. Now will you let me do my work, Barush? Go away!”

2.

Cahan thought he would have a moment of peace, but he had to meet with his business managers, who didn’t want him to contribute to so many strike funds in the Forward’s name. But a socialist paper had to support the strikers and their families. And all he had to do was show his managers the Forward’s circulation printed near the banner on the front page: 139, 871. They couldn’t fire Cahan. His readers would follow him to any paper where he decided to run. So he mocked their talk about money and sent his managers away.

He attacked Tammany Hall and the police in editorial after editorial, and vowed to rid Allen Street of its streetwalkers. “It’s a Jewish plague,” he wrote, “worse than Job had ever seen. They linger right under the El, these Tillies and Sophies, half of whom are unwed mothers belonging to some downtown cadet. They toil in the shadows, bring their clients to a rotting tenement room, and fornicate in front of their own little sisters, who will join this streetwalkers’ paradise in the near future. Shame on us all.”

Cahan was at his best as the penny author Max Vilna. He preferred these wild children’s romances to his East Side tales of plodding immigrants, grocers on the rise, dreaming about the Allrightniks’ Row of Riverside Drive, or a young garment worker seduced by her boss’s favorite son, a ne’er-do-well who would end up as a faro dealer at a Grand Street den. He would write about Cossacks and temptresses who could drain the blood out of a man.

But the editor could feel his empire collapse. The Forward covered every step in the macabre dance of the European powers with all their secret and not so secret alliances, but his readers were much more interested in heartbreak and romance in the Jewish quarter. The shifting alliances in Europe had become perilous for the Jews as borders began to close. Fewer boats left from Hamburg. Ellis Island was idle on certain afternoons. And sometimes, when he had business near Battery Park, and he could stare out at that ponderous brick and stone station, it looked like Atlantis in the mist, about to fall right into the sea. That’s how fragile the world of Jewish immigration had become in 1913; there were less and less escape routes, more and more pogroms.

Cahan didn’t believe in a static universe of skullcaps. Yossele Rosenblatt, the greatest cantor on earth, could sing his heart out at the Roumanian Congregation on Rivington Street, draw merchants and music lovers from uptown, make the sparrows hover over the synagogue searching for his high notes, as the cantor’s business agent loved to boast, but even Yossele couldn’t stop the exodus of Jews from the Lower East Side. Cahan himself was partially at fault. The Forward preached assimilation. It was a Yiddish paper with a Yankee accent. He advised fathers to send their sons to City College, knowing full well that these sons would forsake their fathers and the Ghetto.

That piercing din of time was against Cahan, like the long whistle from one of the ocean liners in the harbor, an endless, mystifying bleat that could have been a capitalist war cry to every socialist between the Bowery and East Broadway. He couldn’t have printed his paper without the revenue from advertisements for White Rose tea. Yet he breathed a taste of socialism into every article he edited or wrote. He attacked the strike breakers, hounded the garment manufacturers, many of whom subscribed to the Forward. He was the shamas of his own little shul that had grown into a skyscraper, and all he could do was watch after the Ghetto’s inhabitants, as he peered down into the Jewish streets.

It was a boisterous slum, denser than Bombay, with sweatshops, cafeterias, a “Pig Market” at the corner of Hester and Ludlow, where greenies fresh off the boat would line up in lugubrious silence, waiting until some con man or sweatshop owner would hire them for a few pennies. There were a couple of choice synagogues with jeweled façades, but most of the shuls in the Ghetto were makeshift affairs — a sunken storefront, or the rotting rear room of a tenement. And Cahan could capture his entire domain in a glance — the alleys, the rooftops, the clotheslines strung across fire escapes, the twin spires of St. Mary’s Church on Grand Street, and beyond the spires to the marble arch at Washington Square, half hidden by that infernal red dust of the Jewish streets, so that the arch seemed to float in the wind, like some magical instrument of American power.

No one else had Cahan’s privileged view, no one had his falcon’s nest. Half the Ghetto had succumbed to darkness, entire streets without lamps. But Cahan could see the lights of the Yiddish theaters along the Bowery, the glow of the El station at Allen and Grand, the somber yellow lamps of the motor cars along Delancey, the skeletons of cable cars sitting outside the repair shop next to the Williamsburg Bridge.

That bridge had swallowed up Grand Street as Manhattan’s great bazaar. A ferry to Brooklyn couldn’t compete with the bridge’s constant traffic and had to shut down, leaving Grand Street an isolated island of coffee houses and fabric shops. Once it had been the home of Lord & Taylor and Ridley’s, the world’s largest retail store, which sat like a magnificent pink elephant five stories high at Allen and Grand, with panoramic windows, a wrought iron façade, a cupola, and a clock tower. Lord & Taylor shunned the immigrants, but Ridley’s was the mecca of Jewish brides looking to build their wedding trousseaus. They could find bargains on every floor — waffle irons, oilcloths, cloaks, lace curtains, corsets, and canaries.

That pink elephant also had a tiny men’s department. Cahan himself had shopped there when he first arrived in America, as an anarchist. In truth, he’d come to bomb the store, though he had never manufactured a decent bomb in his life. He went through the large hammered metal doors at 311½ Grand, expecting to find a capitalist palace of clothing dummies, haughty sales clerks, and pyramids of perfume bottles. But he was disarmed after his first step, as he heard the canaries sing from their cages on the second floor. That soft, sweet hum tantalized Cahan, followed him wherever he went.

The ground floor was swollen with immigrants, girls in their shawls and dresses that looked like burlap sacks, and thick Russian boots that would have served them well in Siberia. These young girls were hypnotized by the brocaded satin slippers that sat on the counters and the shelves, some with buckles and ribbons, others without. They wanted to fondle the slippers, but were frightened of the clerks and the enormous cavern of the department store. The salesgirls tried to help. That’s what troubled Cahan. These weren’t the heartless Yankee witches of Lord & Taylor, who could send you howling into the street with their icy stares. The sales clerks at Ridley’s had memorized a few Yiddish sayings, but that wasn’t enough to ease the hysteria of the immigrant girls.

So the anarchist stepped in. He’d already had a few classes at the public school on Hester Street. He spoke Russian and Yiddish to the immigrants in their shawls, and English to the clerks. The girls were allowed to fondle the shoes, touch every ribbon and jewel. No one barked at them. The sales clerks were content. One or two of them crumpled a handkerchief to their eyes as they watched the rapture of the immigrant girls, whose roughened hands darted like little wily animals .

A curious thing happened as he stared out his window at the Forward. A kind of screen had slipped in front of his eyes, like the outlines of a manuscript that would have enriched a Talmudic scholar, and Cahan could see much deeper into the Ghetto, as if it consisted of multiple layers that he could manipulate with his eyes. And there was Ridley’s, rising above the elevated tracks, with its clock tower. And not only that, he could listen to the clop of the horse car that was bringing Brooklynites to Ridley’s from the Grand Street pier. The editor didn’t see one immigrant girl on that car. All the women wore bonnets and fur collars; they must have been on an excursion to their favorite Manhattan shop.

It was even more curious, because he could hear the canaries sing inside Ridley’s; the sound rose above the clock tower with a kind of deafening warble. Ah, he muttered to himself, the master of A Bintel Brief is losing his mind. And it got worse. He noticed horsemen ride the darkened streets in a perfect line; this wasn’t a mounted patrol from the police stables. Not even such an elite squad of horsemen had the radiance of Russian riders. These were Cossacks in their blood-red blouses and white fur caps rumbling toward Seward Park with their sabers. A pogrom, he whispered, on the Lower East Side, with its own public library and the old Tenth Ward’s Republican Party headquarters a few steps from the Forward building. It was some sort of havoc from the devil, who could deliver Cossacks across the ocean and destroy this strange Ghetto with its theaters and newspapers and a few synagogues as ornate as Babylon.

Cahan closed his eyes. The Cossacks disappeared. And Ridley’s dome was gone, with all the canaries. He gathered up a few manuscripts in his Moroccan leather briefcase and ran like Satan’s own accomplice from the tenth floor.

The Baron of East Broadway is excerpted from Ravage & Son, a novel to be published by Bellevue Literary Press in August.