How a ‘wise man of the shtetl’ evaded Soviet repression and antisemitism to achieve international fame as an artist

For a time, Ilya Kabakov was the only artist from the Soviet Union to have a successful career in the West as well as within the USSR

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s Strange City installation in Paris, 2014. Photo by Getty Images

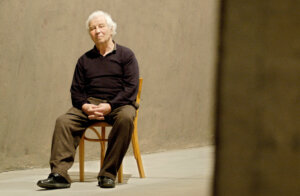

The Jewish painter and installation artist Ilya Kabakov, who died May 27 at age 89, proved that surviving, and even thriving, in an antisemitic society can permanently alter a sense of personal identity.

Born in Ukraine to working-class Jewish parents, he was accepted to study at prestigious schools such as the Leningrad Academy of Art and V.I. Surikov State Art Institute, Moscow, where he opted for a course in graphic design and book illustration.

This specialization guaranteed him privileges as a member of the Union of Soviet Artists, while more outwardly ambitious colleagues studying painting or sculpture attracted perilous attention from the Committee for State Security (KGB).

Kabakov was ostensibly obedient to the Communist party line as illustrator for the 1963 children’s book The Alphabet of Our Life by Evgenii Permiak, an ideological tract for Soviet youngsters. Collaborating on such regime-worshipping publications allowed him leeway for private artistic expression. He was careful not to overstep limits by making public his more personalized, individualistic creativity.

So, although in 1956, Kabakov visited Robert Falk, a fellow Soviet Jewish painter who had fallen afoul of the government, he was careful not to imitate Falk’s trajectory. Kabakov readily acknowledged that in 1974, when the Jewish painter Oscar Rabin invited him to participate in an open-air exhibit of unofficial art, his reaction was to refuse fearfully.

Kabakov added that Rabin’s outdoor group exhibit would be “broken up by bulldozers and street sweepers.”

Outwardly conforming and inwardly developing into a major talent, Kabakov apparently had limited time to dwell on Yiddishkeit. Asked in 1998 by art historian David Ross about his sense of Jewish identity, Kabakov replied: “We all belonged to the Soviet religion.”

One way of coping was to invent an artistic alter ego, who was undeniably Jewish but also safely dead. Kabakov concocted a biography of a certain Sholom Rosenthal, an artist who changed his first name to Charles in Paris, before dying prematurely in a car accident.

Like Kabakov, Rosenthal was also born in Ukraine of Jewish origin, yet Rosenthal’s fictional training with the abstract artist Kazimir Malevich and early death in 1933 clashed with the paintings Kabakov created for him. These were more in the 1950s tradition of Soviet Socialist Realism that Kabakov was exposed to in his youth.

Kabakov’s installations, including those created before he departed the USSR for the West in 1988, identified the historical past with dreck. “Box with Garbage” (1981) and “The Toilet” (1992) were examples. “The Toilet” featured three Soviet-era primitive stalls with holes in the ground, situated next to living areas, as they were in many apartments of the time. As a privileged worker, Kabakov never lived in such sordid conditions.

As Kabakov noted in a commentary to another installation, “A Garbage Novel,” trying to recover traces of Russian Jewish history is doomed to failure; instead of “preserved Jewish places,” only “half-residences, half-ruins, quiet and petrified melancholy, despair” appear to have survived.

Yet amidst the bric-à-brac hoarded to compile Kabakov’s installations are some with resonances of Judaism. The Slavicist Harriet Murav has observed that in “The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment,” ostensibly mocking the Cold War space race, an “object resembling a Jewish prayer shawl … with its characteristic stripes and fringes,” is visible, with simultaneous resonances of flight and mourning.

Murav further identified amidst the hegdesch (mess) an echo of Marc Chagall’s 1938 painting “White Crucifix” in which Jesus is wrapped in a tallit. Such details could have multifarious meanings, as Kabakov’s Jewish artist friends and colleagues knew, admiring his verbal skills in finding sometimes contradictory significance in his own creations.

In a memoir, the dissident Jewish artist Anatoly Brusilovsky described Kabakov as “like the wise man of the shtetl” in his ludic manner of interpreting his works. Accepting the compliment, Kabakov was also cagey, and refused to endanger himself and his family by outwardly opposing the regime: “I was not a dissident,” he told an interviewer in 1995, adding: “I did not fight with anything or anybody. The word does not apply to me.”

So he was unlike such Russian Jewish colleagues as Aleksandr Melamid, a Conceptualist and performance artist who fearlessly parodied approved Soviet propagandistic art, and faced censure for doing so.

Avoiding this sort of chutzpah, Kabakov was aware of his fortune in being able to function as a self-defined “bureaucrat” in the Soviet system, followed by even greater material wealth in the West. His works, with their combination of semi-nostalgia for the Soviet days with a certain sardonic or ironic twist, appealed to Jewish oligarch collectors like Leonid Mikhelson and Roman Abramovich.

Mikhelsen bankrolled The Strange City, a vast installation created by Kabakov and his wife Emilia in 2014 for assembly in the Grand Palais in Paris. Abramovich spent tens of millions of dollars to acquire works by Kabakov, who eventually became Russia’s most expensive living artist, with a painting from 1982 selling at auction in 2008 for $5.8 million.

Other Russian Jewish artists, some of whom were forced to flee their homeland, knew that Kabakov was the sole Russian artist to have a major career in the West. Some ascribed this success to the universal themes in his works.

In 2007, the wife of Michail Grobman, an eminent near-contemporary of Kabakov who emigrated to Israel in 1971, informed Haaretz that her husband’s work sold at a mere fraction of the prices Kabakov was fetching.

Yet despite this prosperity, Kabakov informed Ross that he never felt that he had emigrated or left his country. “My mentality is Soviet,” he said. “My birthplace is the Ukraine; my parents are Jewish; my school education and my language are Russian.”

Yet subtle or implicit signs of Jewish inspiration complemented his compositions, not least in his educational project The Ship of Tolerance, first launched in 2005, in which schoolchildren learned to appreciate diversity by creating artworks.

Echoing the themes of travel and escape often seen in Kabakov’s works as well as voyaging predecessors such as Benjamin of Tudela, The Ship of Tolerance is essentially utopian. And as the Talmudic scholar Michael Higger’s Jewish Utopia (1932) underlined, seeking a prophetic ideal of social justice is a longtime Jewish preoccupation.

“We are both Jewish,” Emilia Kabakov told a Polish interviewer in 2006 — living in a world of art dissociated from common labels such as nationality or other identities: “certainly” not Ukrainian, according to his wife, but Ilya Kabakov sometimes identified himself as a “Soviet man” since he lived through that era. Yet, she noted, “we can’t say he is Russian” because that would imply a mindset, culture, and other factors that he did not have.

As a perennial Soviet Jew, Kabakov mastered survival techniques to excel in achieving a safe haven in the East and West, an achievement no less startling and noteworthy than his inspired artistic creations.