How I stumbled upon thousands of Holocaust-era letters and traced the stories behind them

The letters were hidden in plain sight at Yad Vashem. Most of their writers’ families had never seen them. Until now.

Courtesy of Yad Vashem

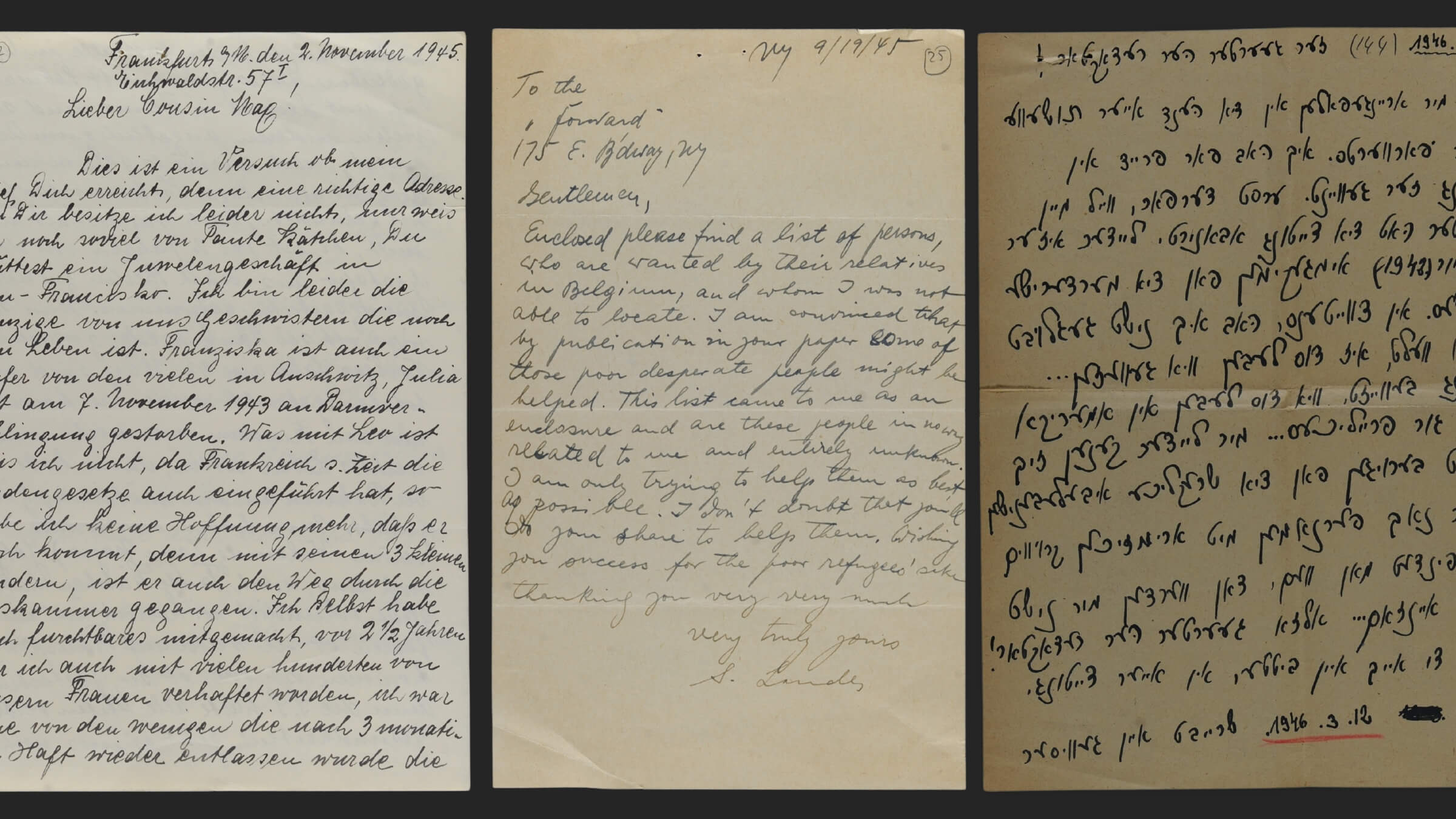

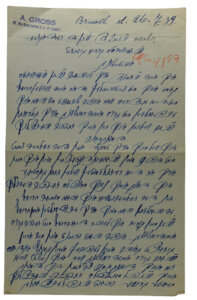

The letter was dated July 17, 1939, and signed by a man named Joseph Gross. He was writing from New York to thank the Forward for helping to find his relatives. Alongside it in the digital archive was a letter written in Yiddish, dated the following week, sent from Brussels and signed by Avrom Gross, Joseph’s cousin.

“I read the letter with such great astonishment,” Avrom wrote. “I have no way of thanking you.”

I stumbled across these letters online, in the digitized archives of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Jerusalem, while searching for references to a column called Seeking Relatives that ran for decades in the Forward.

They were part of a collection donated, upon Yad Vashem’s founding in 1953, by a man named Isaac Metzker, a Forward editor who oversaw the column for years. I soon discovered that Metzker’s files included some 15,000 documents relating to Seeking Relatives, letters and notes that hinted at the way the newspaper connected thousands of Eastern European Jews with family in the U.S. before, during and after World War II.

I had been looking for information about Seeking Relatives in June 2022 for what I thought would be a fairly straightforward article to help commemorate the Forward’s 125th year of operation. Instead, Metzker’s files would lead to more than a year of painstaking reporting in partnership with the Forward’s archivist, Chana Pollack.

I downloaded and sorted through the letters, each marked with a handwritten “18” for the mailbox of the Seeking Relatives department, and searched online for the descendants of the letter-writers. Chana translated dozens of Yiddish-language letters and pored over hundreds more. Friends and acquaintances were enlisted to decipher Polish, German, French and Russian dispatches.

We wanted to find a handful of letters to represent the vast universe of European Jews who contacted the Forward for help during and in the aftermath of the Holocaust. We selected messages from refugees, ghetto residents, prisoners and survivors, and set out to tell what happened to the people in the letters and those they were seeking.

Three survivors who appeared in the Seeking Relatives column, Erika Mandl, Steven Metzler and Aviva Greenberg, were proud to share their stories with me; another man, who only as an adult pieced together how he survived the war, chose to keep his story private even after all these years.

The children and grandchildren of the letter-writers whom I tracked down generally had never before seen the letters I shared with them, letters that in some cases made possible their very existence. Some did not know the details of their parents’ or grandparents’ war stories, or who was responsible for their rescue.

Alongside the Yad Vashem archive, similar databases at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution also proved critical in learning the fates of Holocaust victims and survivors. So did the records of aid organizations like the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the Joint Distribution Committee.

I searched census records and clicked through old telephone books to find the relatives who many of the survivors were seeking when they wrote to the Forward. Military records helped me find the soldiers who brought back letters, and genealogical records and obituaries helped me track down their descendants for interviews.

This was all made more difficult by the fact that many of the names people used when they wrote to Seeking Relatives changed over the years. Immigrants often rotated between their Yiddish, Polish and Americanized names; transliterated spelling variations were dizzying. In his own files, the editor Isaac Metzker is also referred to as Metzger, Mecker and a pen name, I.M. Kersh. And many women changed their name after marriage — and divorce.

I spent dozens of hours talking to survivors, soldiers and their children and grandchildren about their family sagas.

Alex Kor and William Kohn were two who knew their parents’ stories of survival well and had already collected historical artifacts and documents. The historian Annette Wieviorka helped me put her family’s story into the larger political context. Frances Kleinman, who was born in post-war Bavaria, helped me understand what it meant to grow up in the shadow of the Holocaust.

But other descendants of Seeking Relatives letter-writers I found did not even know that their parents had family members in the Holocaust, or that their fathers had liberated concentration camps. It spurred me to research my own family’s history. I learned that my grandmother never mentioned her own aunts, uncles and cousins left behind in Eastern Europe.

Oral testimonies, newspaper clippings and personal papers stored in archives helped me fill in the gaps. Often, I felt my research was a race against time, as Holocaust survivors are dying every day.

Last summer, shortly after I discovered those letters from Joseph Gross and his cousin Avrom, I managed to find records of an Abraham Gross who had escaped Belgium with his family in 1940 — months after the thank-you in the Yad Vashem archives.

I learned that Abraham had become a diamond dealer in New York, opening Abraham Gross & Sons in 1945. He died in 1976, but his firm was still in business, in Manhattan’s diamond district. So I dialed its number.

I ended up speaking to Abraham’s son Harry Gross, who had lived in Belgium in the 1930s. He questioned whether we were talking about the same man: Avrom Gross’s letter had a Brussels address; Harry’s family had lived in Antwerp.

A few months later, also in Metzker’s files at Yad Vashem, I found a clipping of the Seeking Relatives column that included Avrom Gross’s original plea for help from the Forward, asking to connect him with his American relatives.

It included several family names and their Polish shtetls. Which gave me enough clues to find Joseph Gross’ grandson, David, who is in his 80s and lives in Philadelphia.

David Gross was surprised to learn that his grandfather had lent a helping hand to relatives in Europe. He knew little about his extended family from Poland. I tried calling Harry Gross back, but the number was disconnected. So I went to the diamond district — Abraham Gross & Sons was on the 14th floor of an old building on 47th Street — to show Harry Gross the copy of the 1939 ad. But the space was empty.

A building employee told me that Harry Gross had recently died. He was 98.