To understand the blindness of our Supreme Court, look to the land of Alfred Dreyfus

As France burns, we can witness the consequences of so-called ‘race neutrality’

Protestors flee from smoke on a street in Nice, France early July 2, 2023, during the fifth night of rioting following the shooting of a teenage driver in the Parisian suburb of Nanterre on June 27. Photo by Getty Images

Bound by shared revolutionary beginnings, France and the United States are often called the “sister republics.” Two seismic events that occurred nearly simultaneously this past week in the two countries reveal that we are even more closely related than we thought.

On this side of the Atlantic, the Supreme Court, once again snubbing established precedent, ended the use of race-conscious admissions at institutions of higher education. On the far side of the pond, meanwhile, tanks are now taking up stations across Paris. But this is not a rehearsal for the July 14 Bastille Day parade, mind you. Instead, the tanks are protecting government buildings. Since the police shooting on June 27 of a young man of North African ancestry, they have become a principal target of rioting youth who have wreaked six consecutive nights of mayhem across France.

These events would seem to have little if anything to do with one another. What could a court ruling that consumes our attention, after all, have to do with the explosion of misrule that consumes French cities and suburbs? A surprising amount, it turns out — at least for someone who, like me, who has taught French history at a public university in Texas for more than three decades and experienced the deep and enduring value of racially diverse classrooms.

To capture the correspondences between current events in France and the U.S., consider the words “republicanism” and “Republicanism.” At first glance, the two terms could not be more different from one another. Bursting into being in 1789, republicanism is the governing ideology of modern France. Based on the revolutionary trilogy of ideals — liberty, equality and fraternity — it holds that all citizens must be treated as full equals before the law and one another. But this comes with a crucial proviso: You must, in return, treat France as your sole source of identity.

Unlike the United States, where we take pride in hyphenated identities, France takes umbrage at citizens who try to do the same. Scorning the pluralism of American society, French republicanism requires that citizens leave their ethnic and linguistic heritages in the countries to which they belong. Given the assimilationist ideals of republicanism, being French is a full-time affair. Remarkably, “race” does not exist as a category for French officials. One of the consequences is that it leaves French historians and sociologists guessing at the size of these communities.

But there is a more tragic consequence: it also explains, at least in part, why France is now in flames. In theory, French republicanism denies the use or utility of the term “race.” In practice, all too predictably, this makes the brute reality of racism even more brutal. How can you correct a corrosive reality when you are not allowed to name it? This, in turn, leads to the unfortunate irony that liberal French republicans, as one scholar notes, are quick to condemn racism though they have also denied their fellow citizens the language and means to respond to its presence.

This presence, moreover, will not evaporate any time soon. According to a study earlier this year by the respected polling firm Ipsos, 9 out of 10 Black citizens have been at least once the victim of racial discrimination in France. This compares, catastrophically, to a similar study done in 2007, when 5 out of 10 respondents declared they were a target of racism at least once. As one polling expert explained, “We have lately seen a liberation of racist language and an escalation of extremist ideas.”

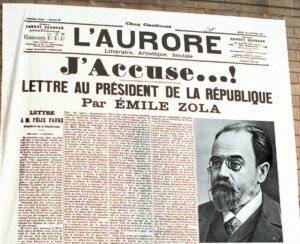

In short, French republicanism, the supposed cure for racism, instead is one of its greatest enablers. Under the veneer of this inclusive ideology, entire swathes of humanity, guilty of having the wrong skin color or practicing the wrong religion, have found themselves suspect in the eyes of the French Republic. This was, of course, the fate of French Jews in the late 19th century, during the Dreyfus Affair, and again during the interwar period, when antisemitic movements and rhetoric were commonplace.

Youths of North African descent who are now torching cars and buildings in France are rebelling against their own grim fate. While their destruction of schools, libraries, and post offices is to be condemned, it is also to be contextualized: These buildings symbolize a state (and its ideology) that has not only failed them, but one that has also failed to acknowledge that it is part of the problem.

Which brings us to our country and the problem of Republicanism. In its 6-3 ruling last week ending the practice at universities in using race as an admissions factor, Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, declared that the programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the equal protection clause.” In the blunt dissent she delivered from the bench, Justice Sonia Sotomayor slammed this decision’s willful blindness. “The court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society.”

In his ruling, Roberts claimed that the ideal of race neutrality, which he embraces, differs from race blindness, which he repudiates. As a result, applicants can still describe in their personal essays how race might have shaped their lives. Yet this is a distinction without a difference, since Roberts explicitly warned admission officials against using the essays to undercut the court’s clear intent to end affirmative action.

It will require the subtilty of a medieval scholastic to parse the difference between race neutrality and race blindness. But there is nothing at all subtle about the lasting harm that centuries of race hatred and bigotry have wrought in our country. Take a shocking, but not surprising study by the Brookings Institution. In 2016, according to the study, the net worth of a white family was nearly 10 times greater than that of a Black family. The researchers concluded that this sorry situation results from centuries of inequality and discrimination, reflecting “a society that has not and does not afford equality of opportunity to all its citizens.”

To repair this damage, neutrality, not to mention blindness, is worse than useless. While imperfect, affirmative action has been one of our most effective tools to undo the staggering effects of racial discrimination in our classrooms. And yet, even before the court’s ruling, the ideologues of Republicanism were doing their best to clamp blinders on our students by purging school libraries and university curricula of the history and legacy of our country’s “peculiar institution” of slavery.

The deaths of Nahel M. in Paris and George Floyd in Minneapolis remind us of the catastrophic consequences of this shared historical aveuglement, or blindness. To honor the approaching national holidays in both France and America, we should demand of our leaders and ourselves something better.