This massive collection of 11 million postage stamps represents every life lost in the Holocaust

The stamps, collected by children, are on display at the American Philatelic Society with letters from survivors and victims

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A teacher’s quest to help students understand the enormity of the Holocaust has culminated in a mind-boggling exhibition of 11 million postage stamps — one for each of the Nazis’ victims, including Jews and non-Jews.

The permanent exhibition, A Philatelic Memorial of the Holocaust, opened last month at the American Philatelic Center in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

The project began when teacher Charlotte Sheer read the Newbery Award-winning children’s novel Number the Stars with her fifth grade class at a K-12 charter school in Foxborough, Massachusetts. The book tells the story of a Danish family that hides a Jewish child from the Nazis.

“I could count on one hand how many Jewish students I had in all the years I worked there,” said Sheer, who is herself Jewish. But “the kids were very moved by the essence of the story. They were really captivated.”

Understanding the magnitude

To help students understand the magnitude of the Holocaust, Sheer showed a video about a Tennessee school that collected 6 million paper clips between 1998 and 2001 to represent Jewish victims.

When the students asked if they could collect paper clips too, Sheer encouraged them to come up with their own idea. Eventually they decided on postage stamps. The logistics worked: Stamps were easy for kids to get, weren’t too heavy and didn’t take up a lot of room. And the symbolism worked: “Postage stamps carry value when initially purchased, but then they’re thrown away as worthless trash — exactly what Nazi Germany was doing with human lives,” Sheer said.

They aimed for 11 million stamps to represent all the Nazis’ victims, rather than 6 million representing Jews alone, in part because of the school’s diversity. “Among the children in my class were kids from diverse cultural, racial and religious backgrounds, including some with learning disabilities,” said Sheer. “It resonated with them in a big way when they realized, ‘Yikes, why do these things make us so different that someone might want to kill us?’”

The stamps pour in

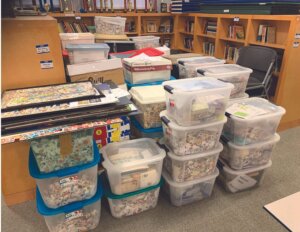

After a year, the kids had only collected 25,000 stamps. But their efforts took off when The Boston Globe and other media began covering the project. Stamps arrived from stamp clubs, synagogues, service groups and collectors culling extras. People donated collections they’d inherited and didn’t want. The school also received boxes of stamps, some weighing 35 pounds or more, filled with stamps and also, to pay for the out-of-state shipping, covered in stamps.

Were any of the stamps valuable? Sheer answered philosophically: “Every stamp represents human life. A stamp that might be worth $10,000 gets lost in the mass of the 11 million” — just like the Nazis’ victims. “It’s a huge metaphor.”

Hearing from survivors

Some donors sent in letters about their Holocaust experiences. “I am enclosing 27 stamps, one for each family member whose life was disrupted by the Holocaust,” wrote Alice Goldstein, whose family fled Germany. She sent another 39 stamps to honor relatives of her husband who were murdered.

Another donor wrote: “My great aunt, Mindl Kotel, was killed by the Nazis in front of her home, along with her husband and three children, ages 11, 8 and 5. I saved five of the prettiest stamps and am putting them with a page showing the truncated family tree. Thank you for remembering.”

Senior citizens and other locals helped organize and count the stamps, and a number of Holocaust survivors not only worked on the project but also spoke with students about their experiences.

Other speakers at the school included Lois Lowry, the author of the book that inspired the project, Number the Stars. “It’s just so hard to visualize huge numbers,” Lowry told me in an email. “And yet teachers always find ways. Postage stamps! Who’d have guessed? Such an imaginative, relevant, and successful project.”

The exhibition

The classroom stamp collection began in 2009. The goal of 11 million stamps was reached eight years later. The American Philatelic Society took custody of the project in 2019, and the exhibition — which was delayed by the pandemic — formally opened June 11. Along the way, Sheer retired and is now writing a book about the project. Meanwhile, many of her fifth graders had graduated from college, and another teacher, Jamie Droste, carried the work forward.

Susanna Mills, editor-in-chief of the American Philatelic Center’s magazine, said the organization embraced the project in response to the rise of antisemitism and surveys showing young people to be deficient in their knowledge of the Holocaust. “We wanted to combat the lack of education, the misinformation, and respond to those news stories about antisemitism and say, ‘This is tangible. This is real. Here’s all the evidence,’” she said.

Artifacts and collages

The exhibition not only displays the stamps and letters the students collected, but also includes postal artifacts like actual postcards and letters sent to and from ghettos and camps. The Nazis permitted mail to “convince the outside world that Jewish prisoners in a camp were fine and alive — but by the time the mail was sent, they had already been killed,” said Mills. “These materials might possibly be the last thing written by a victim of the Holocaust. And that’s powerful.”

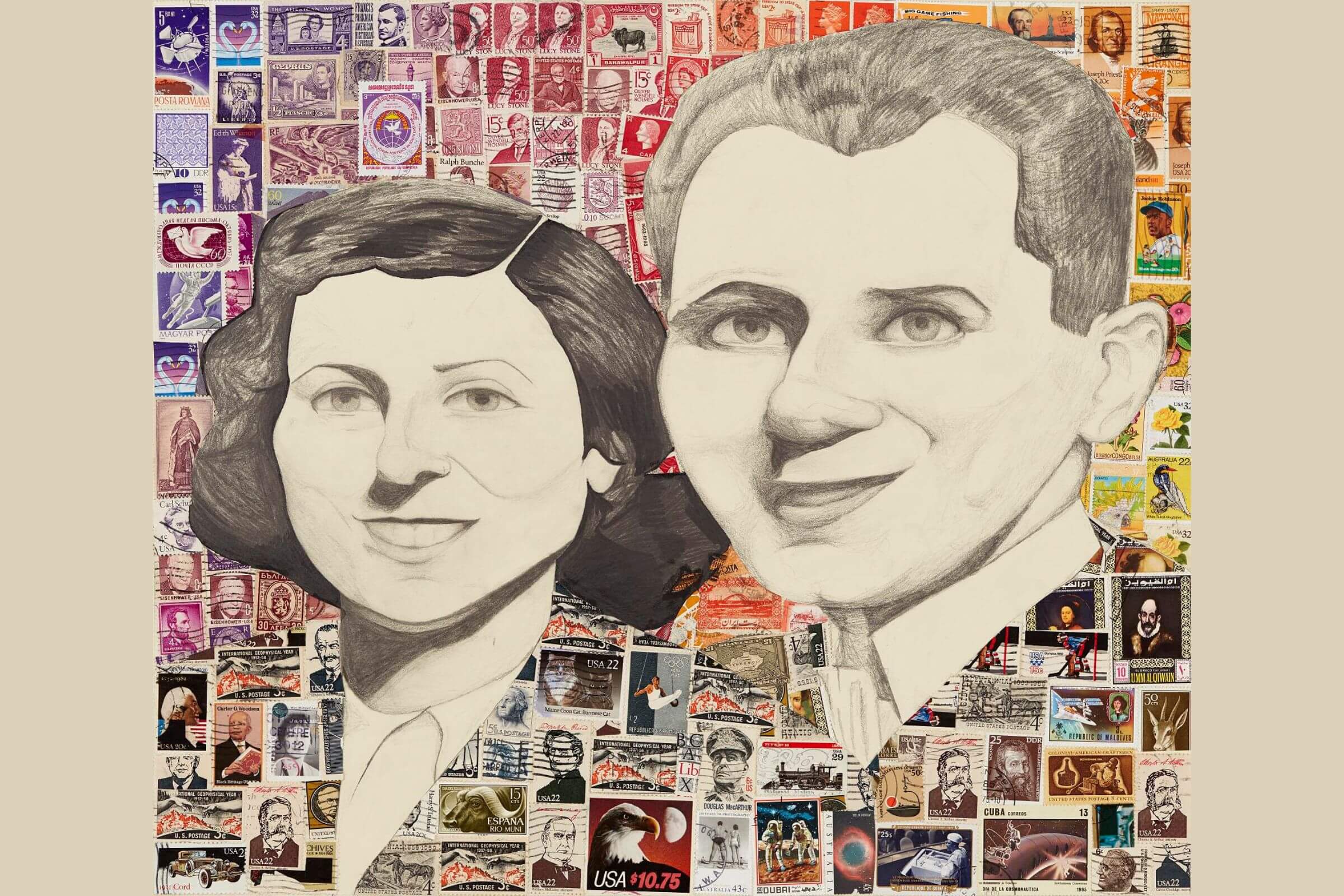

Also on display at the Philatelic Society are 18 collages the students created using stamps. Sarah DeFanti, one of the first fifth graders to work on the project, made the final collage in the series, themed “L’Chaim, To Life,” when she was a high school senior. Central to the artwork is a sketch of an engagement photo of a Holocaust survivor the students met, Sam Weinreb, and his bride, Golde.

Sam’s story

Sam and Golde had been childhood friends; they reunited in a displaced-persons camp where he’d been taken after fleeing a death march from Buchenwald. DeFanti became so close with Weinreb that she arranged for him to receive an honorary high school diploma — he’d never completed his schooling — with her graduating class. “You must always have hope,” was one of his mantras.

DeFanti kept up her relationship with Weinreb after going off to nursing school, visiting him often at a Jewish nursing home in Brookline, Massachusetts; when he died in 2021, she attended his shiva. DeFanti, who now works at Massachusetts General Hospital, said Weinreb’s friendship and the stamps project had a profound influence on her life.

“We try to avert our eyes and look away and not deal with the ugly truth of what happened,” she said. “But having my eyes opened and being introduced to this community really showed me a few things. You never know what somebody has been through. Sam’s spirit could have been broken a million times over but he came out a smiling happy guy for the most part. I think it helped me develop patience and a perspective of, ‘You don’t know what people are going through, but everybody deserves dignity and kindness.’”