Elie Wiesel reviewed ‘Oppenheimer’ — and it made him shudder

In 1969 the author of ‘Night’ was shaken by a play about the father of the atom bomb

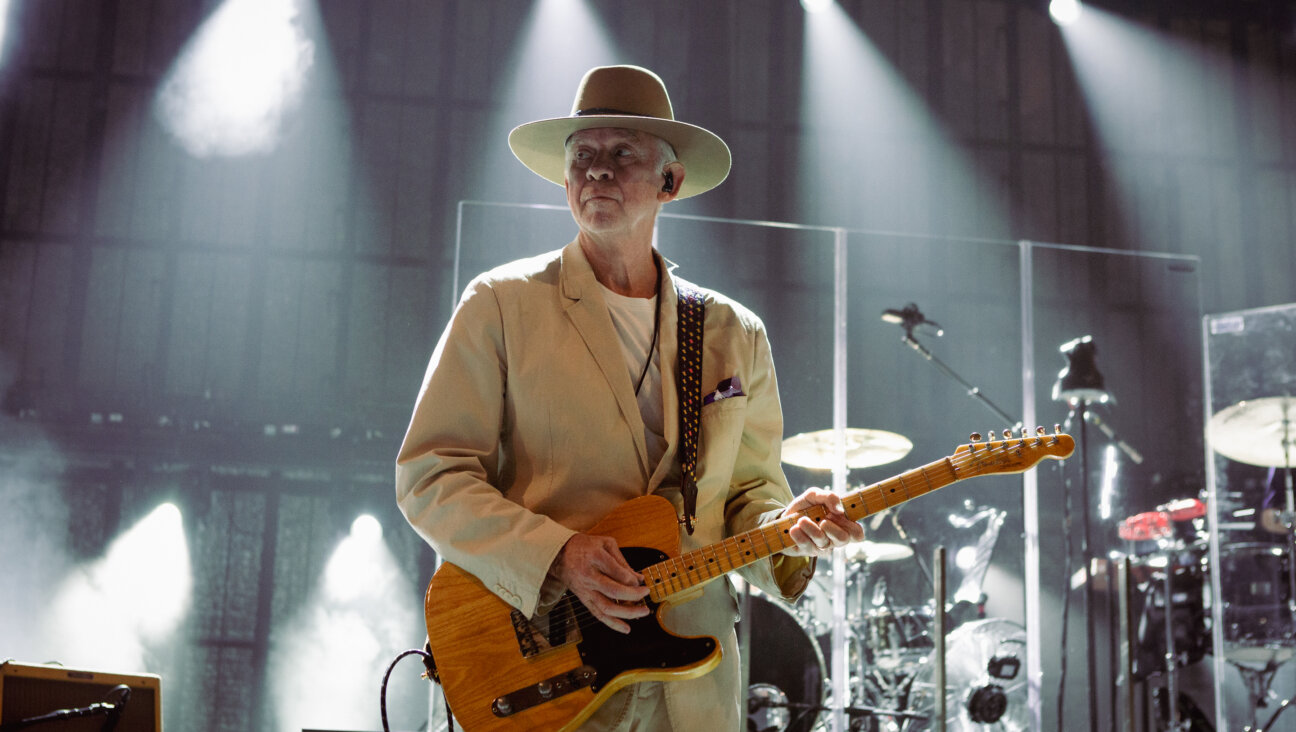

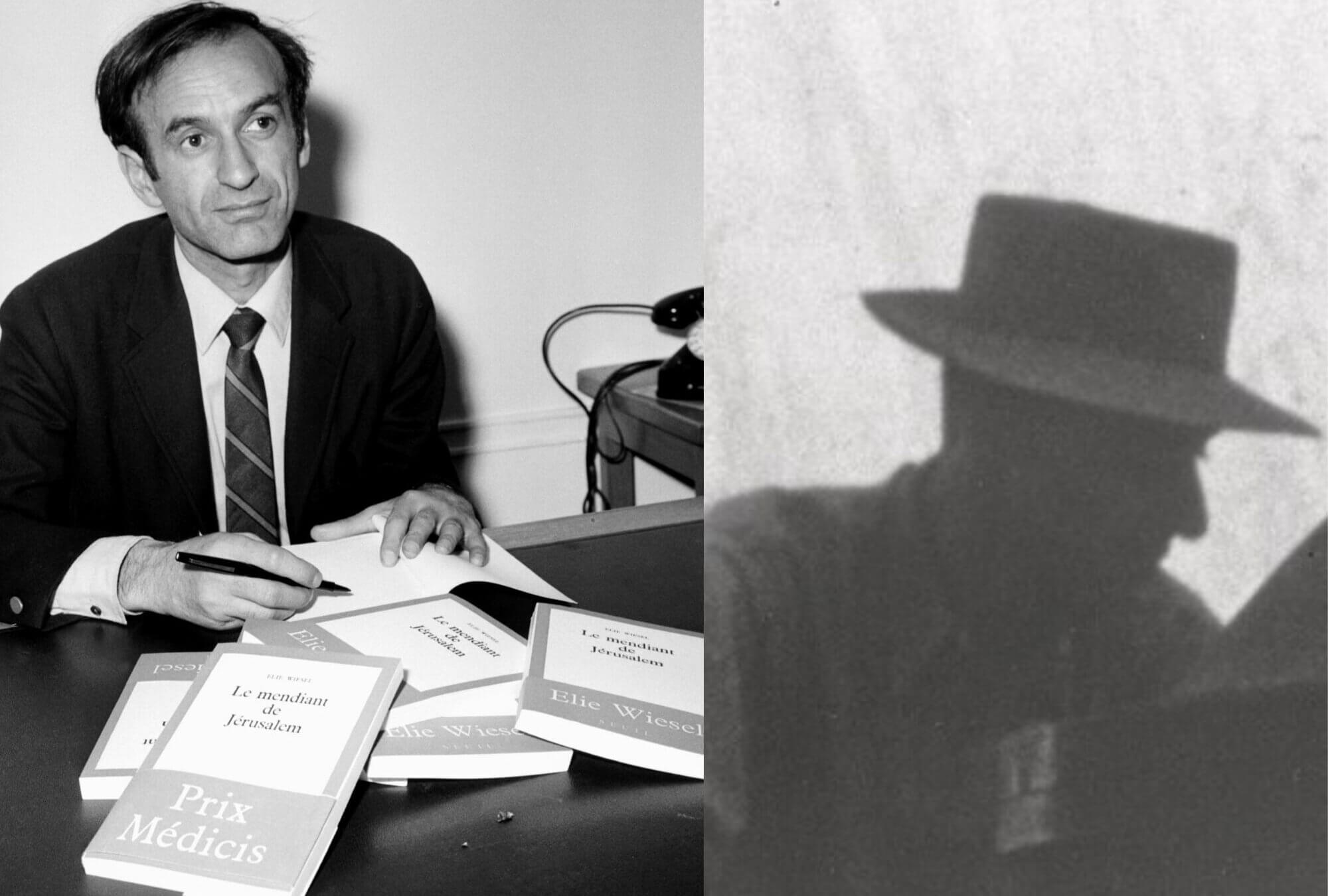

Elie Wiesel once meditated on the “enigma” of the man who shepherded the atom bomb. Photo by Getty/Wikimedia/Canva

Editor’s note: In March 1969, in a rare piece of theater criticism, Elie Wiesel was moved to write about a production of German playwright Heinar Kipphardt’s In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, based on the physicist’s 1954 security clearance hearing. Oppenheimer objected to the play for what he called “improvisations which were contrary to history and to the nature of the people involved,” including its choice to present him as regretting his work on the Manhattan Project. But watching it on Broadway, Wiesel “shuddered” at what he regarded as the play’s “truth.” The article, originally published in the Forward on March 12, 1969, is below.

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by Senior Writer Benyamin Cohen.

When McCarthyism swarmed over America, I was still living in France. It’s still hard to comprehend how one demagogue with several followers managed to terrorize an entire nation. How was one hysteric able to endanger the very foundations of American democracy?

Naturally, there were logical reasons — the Korean war, the Soviet atomic developments, the spread of Communism and its aggressive ambitions. The most powerful country in the world had at once lost its monopoly on all its domains. Suddenly Stalinism’s real face was revealed and so doubts about Roosevelt’s loyalty to the Russian dictator wasn’t a costly mistake. Bringing forth circumstances for an irresponsible demagogue with an answer to everything and a scapegoat for all sins.

It’s difficult, practically impossible, to digest that era’s psychosis. Seems to me the same is true for many American citizens. They recall the events, but avoid speaking about them. It’s almost a taboo topic: it’s not to be investigated, in order not to open an old wound, an ancient shame.

I mention this now because of an innocent coincidence. I had the opportunity to see Heinar Kipphardt’s play about the Oppenheimer investigation at the Lincoln Repertory Theatre. The experience was so deep, I felt an obligation to report to readers, despite the fact that I’m not a professional theater critic, nor do I want to infringe on my critic colleague’s boundaries.

Why did the play cause me to shudder? With its content and presentation, it ripped through me and made me hopeful once more about the individual’s struggle, and the visions of artists and dreamers.

It shook me up due to its portrayal, its truth. Robert Oppenheimer intrigued me for years: his poetic genius, his tragic fate. Despite a deeply felt humanism, he created the atomic bomb: despite being pro-communist in the 1930’s, he remained loyal to America: despite being a notable Jew, he remained at a distance from Yiddishkeit.

How does one weave together so many contradictions? How to clarify so many childish errors (during the investigation against him) and such an acute mind? What did he wish to achieve, and did he achieve it and if so, when?

As I mentioned, I wasn’t living in America when, as a result of the McCarthyist psychosis, the sadly, well known investigation began about Oppenheimer’s loyalty. But I read everything about the case—and am not any smarter for it.

It often seems to me that he was a pretentious intellectual, dancing at several weddings at once, while worshiping several gods simultaneously. He wanted to develop weapons, but not have to use them: befriend communists, but toss their ideas; engage with international political issues but only as a scientist not as a politician. His identity was so split, so variously defined that he alone didn’t fully know what he thought.

And so, at his apex, as well as in the darkest moments of his career, he presented critical introspective questions having to do with human knowledge: at what point are we remaining loyal and to whom? At what point must we step up and say ‘enough?’ Those questions rattle all atomic thinkers. They know that today they are sitting in secure laboratories toying with abstract concepts the results of which could be the destruction of millions of souls. Intellectuals aren’t free from similar doubts. One can fool around with words in order to write a poem or allegory. But how did Oscar Wilde put it? “One man’s poetry is another man’s poison.” Not for nothing did Oppenheimer at the time of the first atomic bomb explosion recall passages from the “Baghavad Ghita”: “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” In the last several generations the Angel of Death has had the final say.

My interest in Oppenheimer also has to do with his being current. It’s no coincidence that so many young people are going to see the play. They identify with his struggle, with his lonely battle against uncomfortable authority, with his protest against bellicose instincts that rage throughout government circles. The college students attempting to revolt against biological weapons production, for example, are following in Oppenheimer’s footsteps. His problem was that he hadn’t created any positive theories. We know what had to be done, but how do we save humanity from suicide. Even Oppenheimer didn’t preach de-weaponization, at a time when the Communist bloc is strengthening its military capability. What is to be done? Oppenheimer had no answer for that. It seems there is no answer.

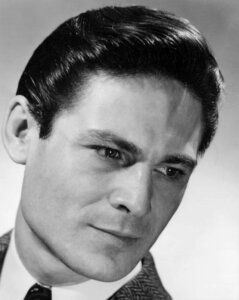

Oppenheimer embodied the questions, not the answers. He endlessly posed riddles, not solutions, and so we must go see him at Lincoln Theatre. Him? Yes. The actor portraying him—a tall, intelligent and palpably Jewish young man named Joseph Wiseman—has so fully incorporated his character that he resembles him physically.

Wiseman, one of the best actors on the English language stage, plays his role with such sensitivity, with such restraint that it’s simply impossible not to be moved. Each word sounds right, he doesn’t stumble. Thanks to him, Oppenheimer is clearly depicted. He answered many of my qualms. I have much to say about Wiseman, but, as I mentioned, I’m no theater critic; I’m merely a witness of Oppenheimer and Joseph Wiseman.