The most prominent Jew in Latin America wore a crucifix at a recent campaign event. Is that kosher?

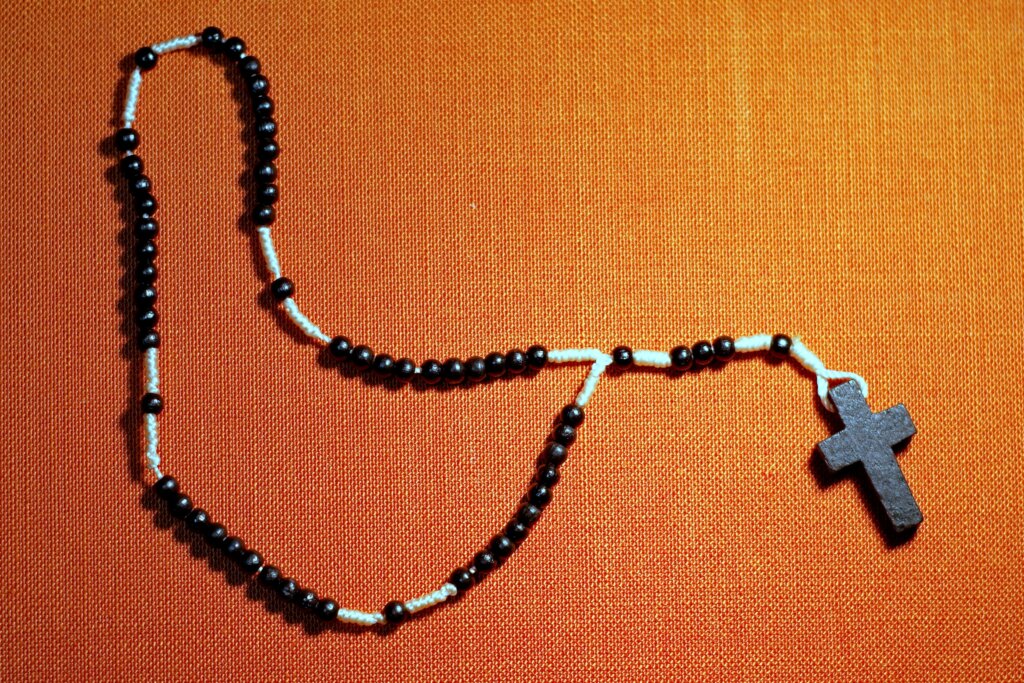

People are divided about Claudia Sheinbaum, the Jewish woman aiming to become Mexico’s next president, donning a rosary

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

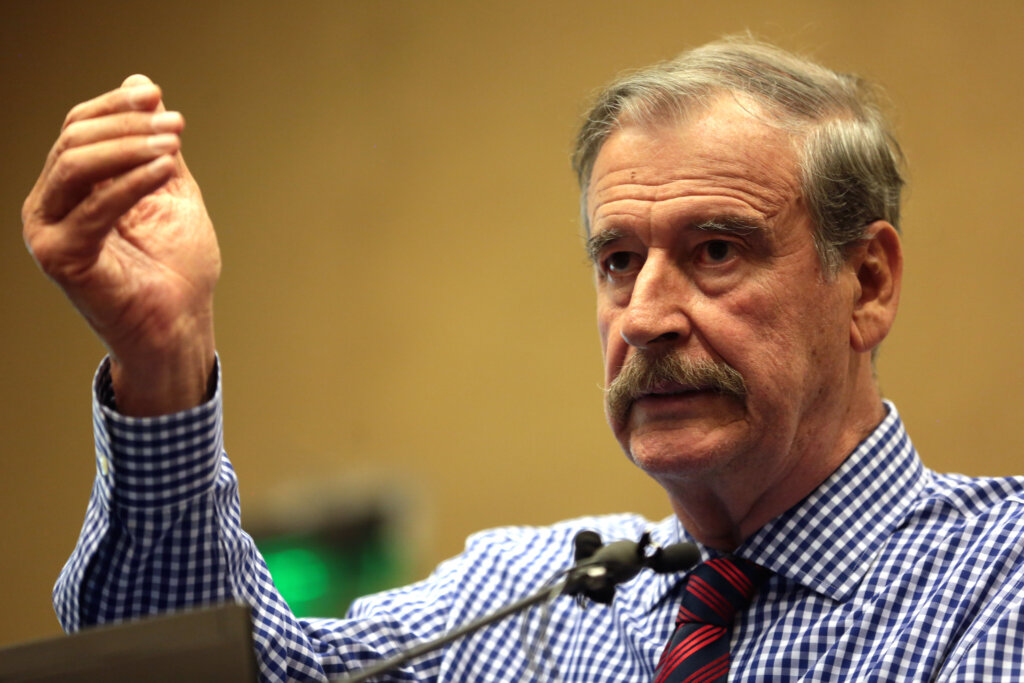

Former Mexican President Vincente Fox led a social-media mob this week in attacking Claudia Sheinbaum, the candidate vying to become the country’s first female and first Jewish president. Fox retweeted a photo of Sheinbaum wearing a rosary necklace and red huipil, a type of embroidered Indigenous garment.

“This woman is so fake,” the original post said. “Isn’t she supposed to be Jewish? If she’s insincere in her religion and her principles, she’ll be insincere in everything else.”

JUDIA Y EXTRANJERA A LA VEZ. https://t.co/MRKxFyI6dC

— Vicente Fox Quesada (@VicenteFoxQue) September 25, 2023

The thread erupted in a finger-pointing match. For those far afield from the Mexican political horse race, though, there were a whole lot of questions. Starting with: What to make of the most prominent Jew in Latin America wearing a crucifix hanging off a string of prayer beads?

As it turns out, in a predominantly Catholic country with a tiny Jewish minority, the answer depends on who you ask.

A cultural symbol

Sheinbaum, 61, who stepped down as mayor of Mexico City in June when she became the governing leftist Morena party’s nominee for president, is a secular Jew whose grandparents are from Lithuania and Bulgaria. She identifies with the history of Jews in political activism more than she does with Jewish religious traditions, but said in a 2018 campaign event that she is proud to be a Jewish woman. She does not usually wear a rosary.

The photograph circulating on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, appears to come from a campaign event in the southern state of Oaxaca on Sept. 24. A video of the event, shared on YouTube by Sheinbaum’s campaign page, shows Sheinbaum entering the event with nothing on her neck, and wearing the rosary about eight minutes in, just before she participates in an Indigenous limpia, or cleansing, ceremony. A day later, Fox incited controversy with his retweet of a photo of her smiling with the beaded necklace on, a crowd behind her. The photo has been viewed millions of times since.

Two days after the event and the day after Fox’s retweet, in a Facebook Live forum, Sheinbaum said she had been given the rosary — a beaded necklace with a cross hanging off it that is often used to aid in prayer to the Virgin Mary — at the event. She put it on and kept it around her neck while she spoke at the demonstration.

While political opponents pounced on the photo that Fox retweeted as evidence that Sheinbaum was insincere or shamelessly pandering, some Mexican experts saw it as a fairly normal political gesture of embrace in a predominantly Catholic country where cultural boundaries are less fixed than in the United States. For Sheinbaum, who has faced relentless false claims of being a foreigner — she was born in Mexico City — it may also have been a way to express native authenticity.

“Catholicism and Catholic symbols can convey Mexican nationalism,” said Julia Young, a historian at the Catholic University of America who studies religious nationalism in Mexico..“She’s donning these two things that are seen as integral parts of Mexican identity,” Young said, referring to the Indigenous dress under the necklace. “She’s saying, ‘I’m Mexican.’”

Catholicism came to Mexico with the first European colonists in the 16th century, and since then has persisted as a core part of national identity. Mexico’s population of 126 million is about 77% Catholic, according to the country’s 2020 census; another 11% are Evangelical Christians, and about 0.1% identify as Jewish.

The combination of the rosary and the huipil, the tunic that is the most common garment worn by Indigenous women in Mexico and other parts of Central America, is significant, according to Young. During the Mexican Revolution in 1910, political leaders embraced the myth that all Mexicans are mestizos, or mixed-race — part Indigenous and part European-Catholic — and that these two cultural influences formed the bedrock of Mexican culture.

All of which is especially important for Sheinbaum, who has faced conspiratorial accusations of being “foreign” akin to the racist “birther” attacks on former President Barack Obama. In July, former President Fox referred to Sheinbaum as a “Bulgarian Jew” on X, adding: “The only Mexican is Xóchitl,” referring to Xóchitl Galvez, his party’s presidential nominee. In his post this week of the rosary photo, Fox blared, “JEWISH AND FOREIGN AT THE SAME TIME.”

This line of attack reflects a classic antisemitic trope, “the Jew as foreigner.” Young said it was a common accusation in Mexico as in other societies, noting that in the wake of the Spanish Inquisition, the Colonial Mexican government fixated on “purity of blood,” and tried to root out people who hid their Judaism.

More Mexican than mole

Sheinbaum, an environmental scientist who was part of a United Nations group awarded the Nobel Prize in 2007 for their work on climate change, has been underscoring her Mexicanness in the face of the birther-style campaign against her. She recently tweeted two images of her Mexican birth certificate, released a campaign song called “Claudia the Mexican,” and said that she is “more Mexican than mole.”

But for some Mexicans — Jewish and Catholic alike — adopting symbols of a religion that is not one’s own is a step too far.

“It’s not an insult to me as a Jew — I don’t care — I think it’s a terrible insult to Mexican people,” said Jenny Torenberg-Gelemovich, a professor of Jewish and world history in Mexico City. “I have very good non-Jewish friends who are not antisemitic and who are very upset by the fact that she’s using those symbols for political reasons.”

Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst in Mexico City, said that he has heard from plenty of Sheinbaum supporters who were dismayed at her decision to wear the rosary in public. “Claudia wearing a cross creates a vulnerability towards her adversaries,” he said, allowing them to say, “‘She’s pretending to be something she’s not.’”

Ilan Stavans, the Mexican-Jewish author of Seventh Heaven: Travels through Jewish Latin America, countered that Sheinbaum’s wardrobe choice is not strange in a country whose national identity is based on the idea of mixing. “I don’t think it’s a betrayal of her own Jewishness,” he said.

Bravo Regidor said that wearing a rosary in Oaxaca is a typical political move. “It doesn’t tell us much about her,” he said, adding that Sheinbaum is “just playing the part, doing what candidates do.But it does tell us something about the people reacting to it in such a way.”

A wave of religious prejudice in Mexican politics

Antisemitism is as old as Catholicism in Mexico, with the colonial government prohibiting Jews from entering the country after the Inquisition. In the 20th century, Mexican leaders promoting the idea of a country based on Catholic, European and Indigenous ancestries excluded Jews, along with other groups, such as Asians and Africans, who had long played important roles in Mexican society.

Sheinbaum, who was elected mayor of Mexico City in 2018 after serving as mayor of its largest borough and as the city’s environmental secretary, rarely faced public antisemitic attacks in the past, said Bravo Regidor, the political analyst. He explained that these recent accusations stem partly from the fact that polls are showing Sheinbaum favored to win the presidential balloting in June 2024.

But Sheinbaum’s travails are also symptoms of a broader trend, he said. In recent years, Mexico has fallen prey to the populist fervor that sweeps much of the globe, and people like Fox are doubling down on an essentialized mestizo identity that excludes Jews and other people seen as foreign.

And it’s not just Fox and his conservative PAN party. On the Mexican political left, antisemitism “tends to be about Jews being a part of the elite,” Bravo Regidor said. Alfredo Jalife-Rahme, a supporter of Sheinbaum’s Morena party who also is something of a conspiracy theorist, accused Sheinbaum of maintaining close ties with Jewish real estate developers in 2012, and more recently said he would not vote for her because she is a Zionist.

Bravo Regidor also said that this type of antisemitism “pairs well” with the anti-elite rhetoric of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, an ally of Sheinbaum who has called Mexican business leaders “a mafia of power.”

Stavans, the Mexican Jewish author, said that even if the backlash against Sheinbaum’s donning the rosary smacked of antisemitism, he thinks the public conversation that it generated is a sign of a vibrant democracy.

“Having grown up in a Mexico that had a one-party dictator up until the late ’90s,” he said, “this kind of vigorous social media, and regular media, back-and-forth about her Jewishness is even healthy. It’s an important moment.”