My relatives were sheltered and saved — but in WWII Poland, they were the exception not the rule

During the Holocaust there were tales of Polish heroism, though far fewer than the current government would have you believe

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

BOCZENEK, Poland — Trudging up a steep hill in the Polish countryside, I followed a farmer whose family and mine enjoy a special bond. His grandfather provided lifesaving shelter to eight of my relatives when Germans were hunting and executing Jews here.

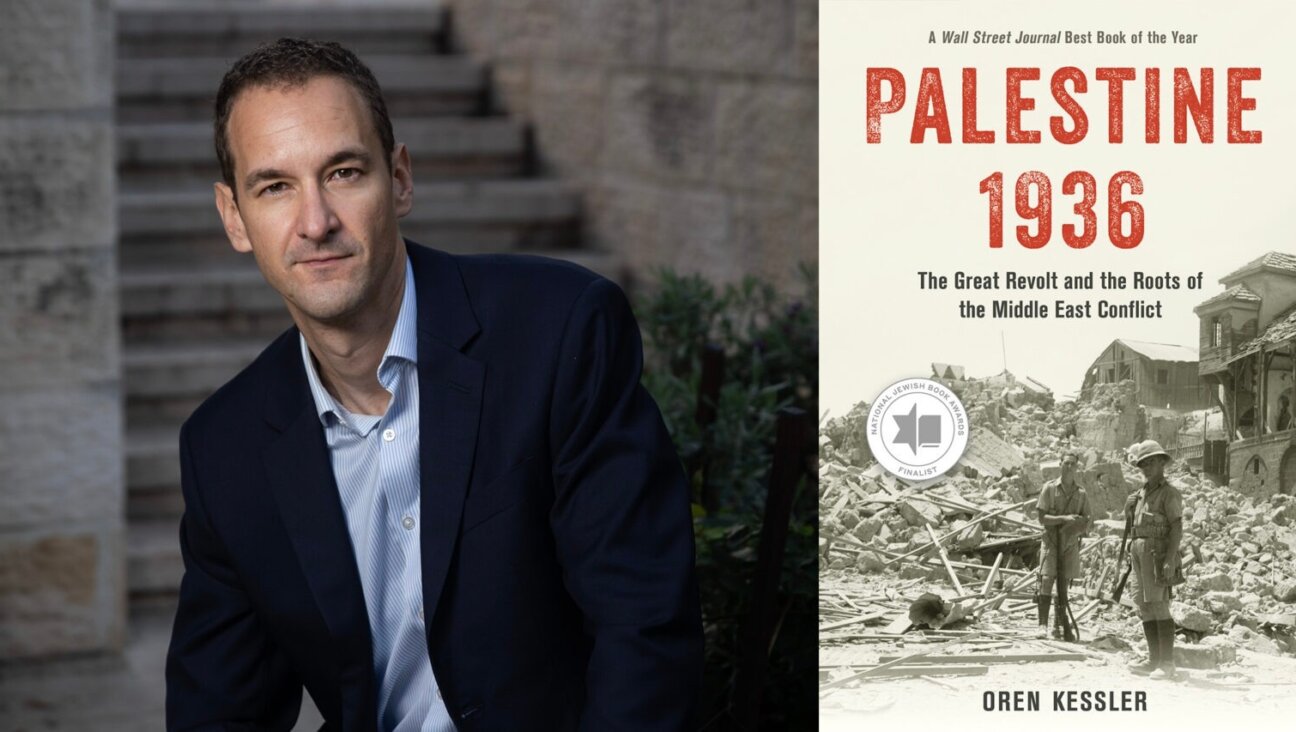

Visiting the families whose forebears hid my relatives has been the highlight of my trips to Poland stretching back to the early 1990s. Stopping by the farm to give thanks to Tadeusz Mleko, the man leading me up the hill, is something I started doing with my cousin Sam Rakowski Ron, one of the eight whom Mleko’s grandfather sheltered for three months in 1942.

The children and grandchildren of the man who hid our relatives never advertised this legacy. Already they bore a stigma passed down for generations. Neighbors suspected them of getting rich off the Jews they hid and held a grudge for exposing the village to the threat from Nazis of collective punishment for harboring Jews, even though that never transpired.

Stories of ordinary people like the Mlekos risking their lives to save Jews are far more rare than the Polish government would have its citizens believe. The right-wing populist government, facing a tough re-election bid on Oct. 15, is perpetuating a false narrative that Polish rescuers were the norm during the Nazis’ deportation and murder of the country’s three million Jews. They did not. Further, the government inflates the number of Poles who were martyred for hiding Jews.

At a lecture the day of our visit with the Mlekos, the Rev. Paweł Mazanka, Metaphysics Department head at Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw, asked audience members how many Christian Poles they thought were executed by the Nazis for harboring Jews. Many guessed tens of thousands, and when told they were wrong, they guessed thousands, the number that Polish President Andrzej Duda offered publicly that very day. No, Mazanka said. “We have to deal with the facts.” The actual number, he said, “is 600 to 800.”

Nowhere is the glorification of the notion that most Poles saved the Jews more prominent than in the recent beatification of a Polish Catholic family that was publicly executed for hiding Jews after a Polish policeman betrayed them. Not far from us that day, an elaborate ceremony with 1,000 cardinals and top government officials attending put Józef Ulma, his wife Wiktoria and their seven children on the path to sainthood in rites livestreamed from the Vatican.

The church even used the Ulmas’ story to underscore its opposition to abortion, initially beatifying the mother’s unborn, unbaptized child, and later issuing a clarification that the child was born during the incident and was baptized in the mother’s blood.

Celebrating the heroism and sacrifice of the Ulmas, who harbored eight Jews from the Goldmann and Grunfeld families for more than a year, is not new. In 1995, Yad Vashem honored them as Righteous Among the Nations.

The timing of the Ulmas’ beatification 28 years later is suspect in the eyes of observers including Canadian Historian Jan Grabowski, who has been sued in Poland for his Holocaust research. Grabowski said in a Facebook post that the timing of the beatification was being “cynically used by people of bad will to distort the history of the Holocaust.”

Also not new are efforts by the Law and Justice (PiS) government to distort Holocaust history. In 2018, the PiS government enacted a law against public discussion of Poles “being responsible or complicit in Nazi crimes.” The law is part of a concerted government effort to deny the collaboration of some Poles with the Nazis and indifference of many Poles to Jewish suffering.

The law has been a tool for the government to attack academics such as Grabowski who have generated reams of solid academic research that contradicts the government dogma of innocence and heroism. Yale University historian Timothy Snyder, in reviewing one of Grabowski’s studies, called it “undeniable” that most of the Polish Jews who had escaped from or avoided the ghettos and camps were murdered in the countryside, up to half of them by Poles.

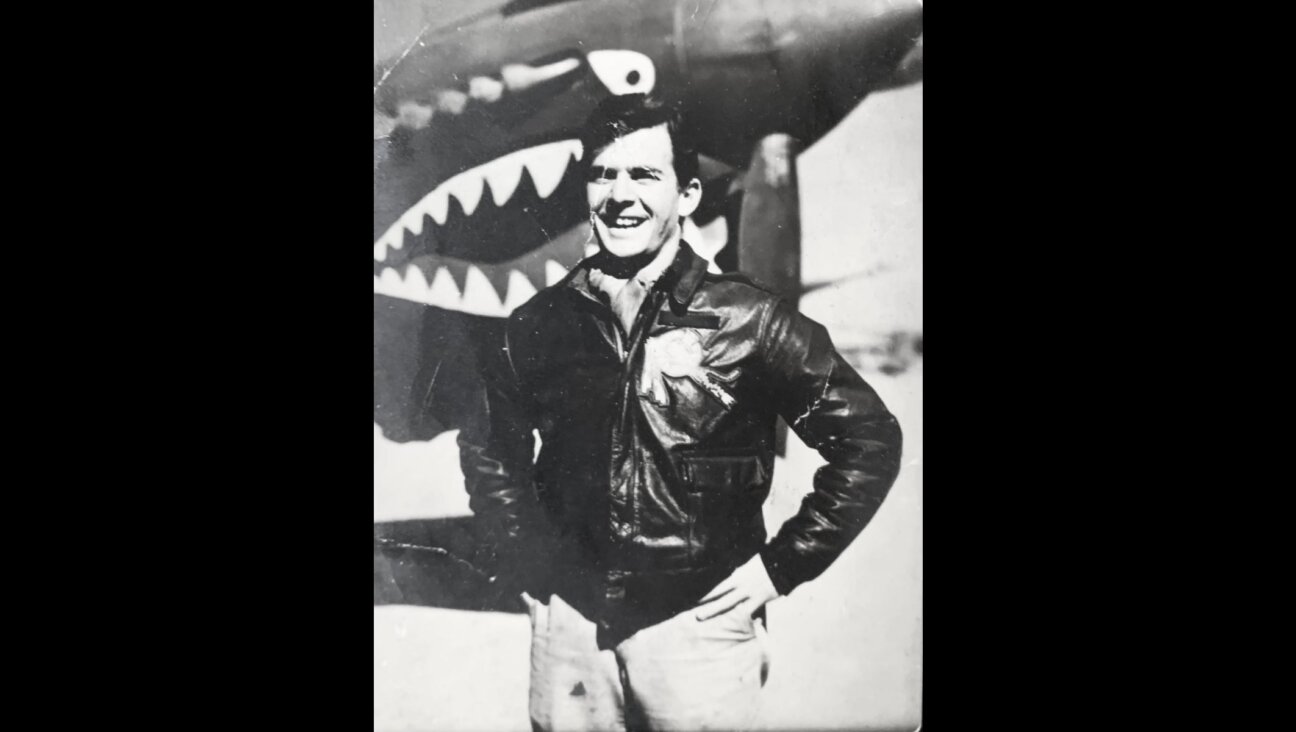

The experience of several of my relatives bears out this scholarship and runs counter to the government’s Holocaust narrative. Atop the hill Mleko showed us, was the scene of an event that proved decisive to the survival of my cousin Sam and his family. In 1942, the Nazis discovered 12 Jews hiding in what was a brick factory of Mleko’s grandfather, now a tilled field. The Germans opened fire. They killed all but a 14-year-old girl, who ran. The Nazis shrugged, leaving her a chance. Then more shots rang out from the gun of a Christian Pole of German descent, keen to curry favor with the Germans, killing her.

That incident at the brick factory shook cousin Sam’s father. With help from Mleko’s grandfather, they left the hiding place and snuck into the Krakow ghetto. The eight wound up in several concentration camps starting with Plaszow, featured in Schindler’s List. Six, including Sam and his parents, survived the war.

But other relatives who remained in hiding with brave and compassionate Poles were not so lucky. In 1944 members of the Polish underground who were engaged in attacks wiping out Jews in hiding as part of maneuvers of partisans aligned with Nazi aims, renegades from other partisans, killed two different families of cousins in hiding. Some 20 members of the underground were prosecuted for some of the murders but received amnesty from the government. For generations, the families who hid them have been shunned by people in their communities for the same reasons Mleko mentioned.

I was in Poland this time to represent Sam at ceremonies in his hometown honoring him as its last Jew. At age 99 he was not up to traveling from Florida to his beloved Kazimierza Wielka. These laudatory efforts started off with the rededication of the prewar cemetery where my great-grandfather is buried.

They continued over four days in multiple towns, packing a schedule with lectures, panel discussions, concerts and a Mass celebrating local Jewish history. The mayors and other event speakers did not openly challenge the government’s Holocaust narrative, but did not espouse it either. Some privately said they are hoping the election brings change.

One speaker went there. A high school history teacher who oversaw the translation of cousin Sam’s memoir into Polish declared before a full auditorium: “The history written in books says that we were all heroes.” But, she said, “this is not true.”

Editor’s Note: Sam Rakowski Ron passed away Oct. 11, 2023.