Surviving the Holocaust, only to endure the brutality of life under Stalin

In ‘Two Roads Home,’ Daniel Finkelstein urges the reader to remember both Nazi and Soviet crimes against humanity

Daniel Finkelstein’s memoir is subtitled ‘Hitler, Stalin and the Miraculous Survival of My Family.’ Photo by Istock

Two Roads Home: Hitler, Stalin and the Miraculous Survival of My Family

By Daniel Finkelstein

Doubleday, 400 pages, $32.50

While Hitler’s genocidal war was destroying two-thirds of European Jewry, the Soviets were deporting hundreds of thousands of Eastern Europeans, including Jews, to Siberia and elsewhere, and starving many of them to death. Yet, writes Daniel Finkelstein, “the public interest in Stalin’s crimes didn’t come. It has never come.”

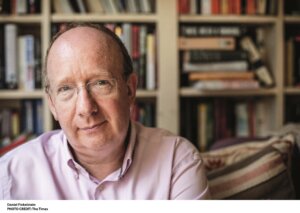

Finkelstein, a political columnist for The Times of London and member of the British House of Lords, wants both tragedies to be known and mourned. His memoir, Two Roads Home, is intended as a historical corrective and a study in parallels. It intertwines the survival narratives of his father, Ludwik, and his mother, Mirjam, whose families were wrenched from their comfortable lives into a nightmare of suffering.

To his ideological passion, Finkelstein adds painstaking research, deep feeling and occasional eloquence. Against a backdrop of mounting repression and horror, Two Roads Home offers “a story,” he writes, “of how the great forces of history crashed down in a terrible wave on two happy families…and finally returned what was left to dry land.”

The book is divided into three parts: “Before,” “During” and “After.” The first offers the backstories of two prosperous, educated families convinced that their Jewishness was no bar to a proud national identity — German in the case of Finkelstein’s Berlin-based maternal family, and Polish for his paternal one in Lwów (present-day Lviv, in western Ukraine).

Finkelstein’s maternal grandfather was a significant figure, chronicled in Ben Barkow’s 1997 biography, Alfred Wiener and the Making of the Holocaust Library. Wiener was committed to the increasingly dangerous enterprise of documenting the Nazi movement and regime. Intermittently destroyed and reconstituted, his archive, eventually known as the Wiener Library, moved with him from Berlin to Amsterdam, and then to London and New York. It became essential to the British war effort, the Nuremberg Trials and early Holocaust historians.

Finkelstein opens in present-day New York and London on a grateful but also cautionary note. “The idea that the value of liberal democracy, and law, and liberty, and tolerance, is a lesson that has been learned and can’t be unlearned seems hopelessly overoptimistic,” he writes. “What happened to my parents isn’t about to happen to me…But could it? It could.” That worry provides the book’s rationale.

The narrative flashes back to Berlin and to Wiener, who combined prescience with an almost foolhardy bravado. He was warning of antisemitism in Germany as early as 1919. His formidable wife, Grete, had a doctorate in economics, a rare distinction for a woman of that era, and served as her husband’s aide and secretary.

In 1933, Wiener met with Hermann Göring, about to become the first chief of the Gestapo. A second, more threatening meeting convinced him it was time to leave Germany. He chose, like Anne Frank’s family, to emigrate to the Netherlands, with his wife and three daughters. (Mirjam, born in 1934, was the youngest.)

In 1934-35, Wiener monitored and helped publicize the Bern Trial, which found that the viciously antisemitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion were a forgery. A contact he made in Switzerland later helped save his family’s life.

Meanwhile, the Finkelsteins — Dolu, Lusia and their beloved only child, Ludwik — were thriving in ethnically volatile Lwów, where Ukrainians and Poles competed for dominance, and both sides were hostile to Jews. But the Soviet-German nonaggression pact of 1939 was fateful for Poland, and for Finkelstein’s family. “Nothing that followed would have occurred without it,” he writes.

From there, the narrative accelerates. For the sake of his archive, Alfred relocated to London in early 1939, leaving his family behind. Their visas materialized too late to save them from the Nazi occupation and deportations — first to the transit camp of Westerbork, then Bergen-Belsen.

The Finkelsteins were no better off. When the Nazis invaded Poland from the West, the Soviets poured in from the East, setting in motion what Finkelstein calls a story of “communist terror,” “little told, often denied, and even now, to most people, entirely unknown.”

With Nikita Krushchev as a neighbor, the Finkelstein home was confiscated, their building-supply company nationalized. Dolu was picked up first and imprisoned under harsh conditions. Then the rest of the family was deported. The author’s great-grandmother managed to escape from a Soviet train, dying, in 1942, of natural causes — a small victory.

Ludwik and his mother, Lusia, ended up on a state farm in Siberia, making bricks from cow dung, living (barely) on gift packages from relatives, nearly freezing to death. Finkelstein details their sufferings with immersive precision.

He brings similar emotion to the story of the Wieners. On the eve of her deportation from Westerbork to the Sobibor death camp, Grete’s sister, Trude, leaves a heartbreakingly hopeful note, concluding with this thought: “you know that the two of us belong together and will find each other again, wherever in the world.”

The sisters’ reunion never happens. But through a bizarre series of coincidences, seeming miracles and near-misses, Grete and her daughters obtain (transparently phony) Paraguayan passports that ensure their exit from Bergen-Belsen. After the Soviets switch sides and join the Allies, the Finkelstein family, too, is saved and reunited. Years later, Mirjam and Ludwik, transcending their dual traumas, meet and marry in London.

Along with highlighting Soviet crimes, Finkelstein has another point to underline. When historians examine the Holocaust, he notes, they see wrong choices and errors of judgment that prove disastrous for Jews and others.

“When you look back,” he writes, “there are so many things that could have been done differently, given perfect knowledge, given perfect people.” It is possible to ask, he writes, “whether greater decisiveness might have helped, or more imagination, or less complacency.”

Finkelstein, shunting such second-guessing aside, endorses his mother’s measured response: “It was the Nazis who were responsible.”