She wrote the book on Israeli horror movies — real-life horror stopped the book tour

Author Olga Gershenson talks about the genre of Israeli horror and the ongoing terror in Israel

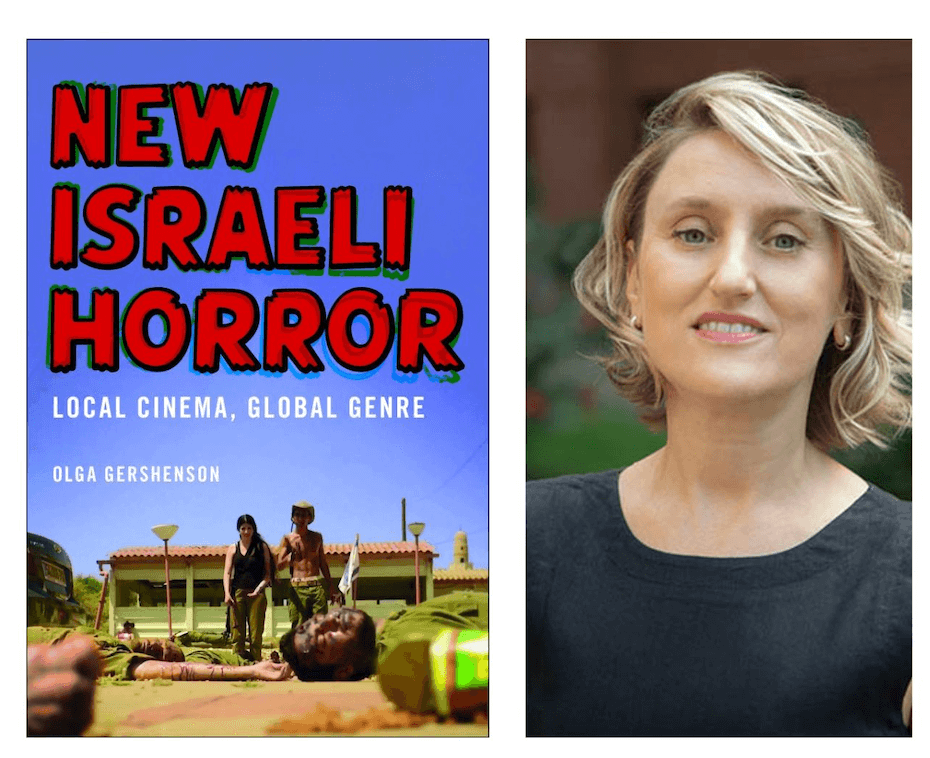

Olga Gershenson with the cover of her new book New Israeli Horror. Courtesy of Rutgers University Press

Olga Gershenson was in Tel Aviv Oct. 6 with a full schedule for the weeks ahead. She was going to speak with authors for an upcoming anthology, visit directors on film sets and promote her new book on Israeli horror films.

Then she heard the explosions.

“The real-life horror stopped the promotion of fictional horror,” said Gershenson.

A professor of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at UMass Amherst, Gershenson was soon evacuated by the university from Tel Aviv to Dubai and is now in Madrid, crashing at a friend of a friend’s apartment. The book tour for New Israeli Horror: Local Cinema, Global Genre, out Nov. 10, has been put on hold.

Gershenson, also the author of The Phantom Holocaust, on Soviet films about the Shoah, has been in touch with some of the filmmakers in her newest book, which analyzes the relatively new wave of Israeli horror. One, Eitan Gafny, whose film Children of the Fall is a slasher set on a kibbutz almost exactly 50 years before Hamas’ terrorist attacks, actually said it may have been a good thing his film never saw a theatrical release — it’s perhaps too terrifyingly close to reality.

The book outlines how, in the 2010s, a group of filmmakers emerging from an underground genre film club at Tel Aviv University Film School, adapted the familiar tropes of horror for a local sensibility. Part of that conversion meant channeling the trauma of past conflicts and the masculine anxiety of a militarized society into zombie films and creature features. In this way, Israeli horror carved out a niche that might one day help the nation to process its current nightmare, though, Gershenson believes, that may be decades away.

I spoke with Gershenson about what makes Israeli horror distinct and why scary movies often emerge in times of relative calm. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You start the book by saying you’re not really a horror native and then you saw the 2011 film Poisoned in Toronto. What about it got you hooked?

I’m not a horror native, but I’m certainly a comedy native. I love comedy. I love humor. I teach Jewish humor at UMass. The Israeli horror films of the 2010s are just incredibly sharp satires of Israeli society and politics. I just love them. We’re all used to Israeli films talking about war and the serious stuff, but it was so interesting to me that you could speak about violence and the army, but in this satirical and very funny way. And that felt very new and fascinating. And so this is what grabbed me, and it wouldn’t let me let me alone until I wrote the book.

It didn’t really start in earnest until the 2010s, with the exception of a few pure precursors that you note. Why do you think it took so long for Israeli filmmakers to tap into genre?

The current war and the current crisis kind of gives us some ideas. When there is a war, and when there is an active crisis, people don’t make horror movies. In some ways there is this theory in horror film scholarship that horror films appear in actually a relatively OK time, when a society, in a way, is safe or secure, and then we can look at our demons. So that doesn’t really surprise us that throughout like ’60s and ’70s and ’80s there are really no horror films. Also back then the dominant horror tradition is coming from the U.S. It’s a U.S. popular culture genre. Then there’s this generational change. These guys grew up in the era of VHS, the era of DVDs, the era of cable television and so they’re exposed to a dramatically different cultural landscape and they’re like, “We want that. Enough with the war movies, enough with family drama, enough with family melodrama. We want to have fun. We want to use ketchup for blood. We want to have our own version of horror movies.”

You break down the way these films function either as conversion, subversion, aversion, and then inversion, which we haven’t really seen yet. Could you explain a bit more about those terms and the way you see Israel maybe being unique in the horror landscape?

I actually think that Israel is not very unique. I think that Israel is head to head with other kinds of newer horror traditions. Israel is part of the global phenomena and the global phenomena is to take these kind of genre tropes that are familiar to us, like zombies, which is totally American, basically starting with (George) Romero, and vampires, things like Dracula, and the various serial killers who are unstoppable, and then do a national spin on them. Israeli filmmakers say, ‘let’s Hebraize the horror.’ And some of them are very intentional about that. And some of them are less intentional about that. They come with their Israeli cultural signifiers and background and interests and messages. The most common choice that the filmmakers take, is what I called “Conversion.” We all know zombies, but we’re gonna set it on the Israeli army base. Perfect, right? And this is Poisoned, for instance. Or it’s a slasher, but we’re gonna set it on a kibbutz, and that’s Children of the Fall. Because of where a horror trope lands, it doesn’t stay exactly the same. Horror fans are familiar with a trope like the slasher trope of the “final girl,” who survives everything. But in Israel, it’s a “final boy,” because it’s on the army base, and they’re very interested in masculinity.

“Subversion” is something that the two most intellectual filmmakers, Aharon Keshales and Navot Papushado, do. They live and breathe popular culture, they have seen everything. Their movie Rabies (2010) is the first Israeli horror film. They’re doing a sophisticated deconstruction of horror tropes: a serial killer in Israel and the action should take place in the woods. There are no serial killers in Israel! There are no woods as such in Israel — there are like these little national parks. Their serial killer never actually kills anyone, and the violence just continues as if on its own. They really kind of pull out the rug from under the foot of Israeli signifiers and from the horror tropes themselves.

“Aversion” refers to some of the filmmakers who are only making films in Hebrew because that’s the language that’s available to them. Things to do with Israeli society are not necessarily in their heart. Some of the films are completely in English. But the interesting thing about these movies is that the Israeli reality keeps seeping in — it kind of filters in.

“Inversion” exists only in some horror traditions — apparently Indonesian horror movies have some kind of native horror tropes. Israel has not produced any horror tropes that are completely disconnected from the rest of horror filmmaking. So it’s an empty set. We don’t have that.

If someone were to get started with these movies — of course there are always people who say they can’t watch horror movies because they’re too scared — where should they start?

The vast majority of them are kind of comedies and kind of not very scary. I put together a website with film clips and references to where you can stream them. The one that is my favorite, Poisoned, which I would say is an excellent starter Israeli horror film has not been released online yet for the sole reason of the war starting.

The only film that really doesn’t have elements of comedy is The Damned, and that is one of the latest ones, maybe The Golem as well, because it took Israelis almost 10 years to make a serious horror film. Even the serious horror films are more atmospheric than scary. You can’t look at zombies in IDF uniforms and take it seriously.

In a lot of these, and Children of the Fall very specifically, the trauma of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the Lebanon War looms very large . Even if we’re years away from this, do you think Oct. 7 will inform future movies?

The 1973 war was 50 years ago. The trauma was phenomenal and it took the filmmakers something like over 40 years to really talk about it. It took that long for the horror tropes to really engage with that trauma, so I think that we should not expect Oct. 7, 2023, on horror screens anytime soon. It’s so raw. Right now the entire Israeli society is not even in PTSD, because PTSD is a delayed response. They’re in the active traumatizing responses as both victims and perpetrators of trauma. What’s happening in Gaza is also horrendous. The awfulness of that, which we don’t know how it’s going to get resolved and when and how — this is not horror film material as of now.

I keep thinking about how people are going to watch these films now after the real-life horrors. I don’t know what’s going to happen to these films and how they’re going to be interpreted and reinterpreted. That is going to be a big question.

Sadly a lot of what we’re seeing is GoPro footage of Hamas. There’s actual horrific footage that is part of the war and the messaging.

Personally, I can watch any level of fictional horror. The moment that I know that it’s been manufactured by filmmakers I can watch anything at all now. But I made a decision starting with Oct. 7 to not watch the real-life violence. I only read the accounts and I refuse to see. Especially as a horror scholar, I think there’s something to visual violence that we’re in some ways habituated to, and I’m very wary of that being circulated and people watching it on their phones in the same way that they used to watch entertainment or fictional violence. That scares the hell out of me.