A Jewish family story about defending a kibbutz in 1948 takes on new meaning

Before the war broke out, ‘Brothers Keeper’ was intended to be a comic book honoring a filmmaker’s grandfather

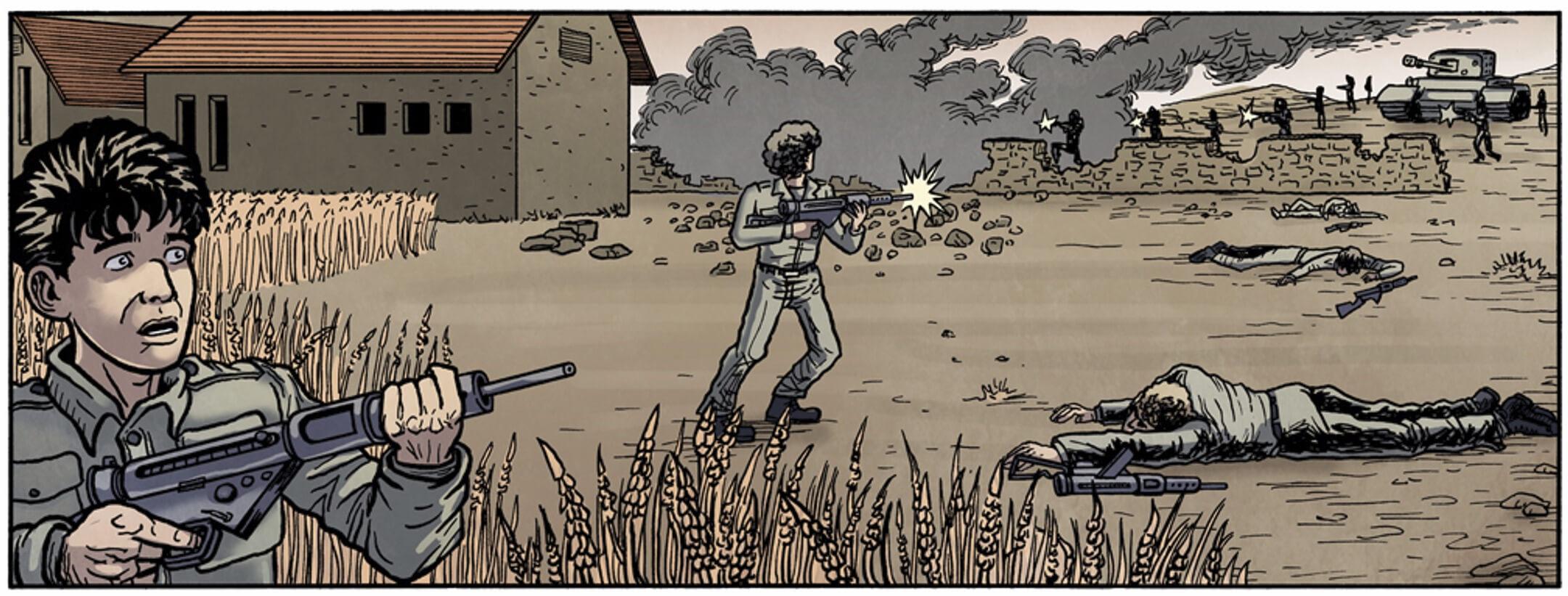

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It was supposed to be “just a story from a war.” It wasn’t intended to impart any kind of grand message and it certainly wasn’t meant to feel familiar or timely. When Arnon Shorr and Joshua Edelglass decided to make a short comic book about the time Shorr’s grandfather was wounded defending a kibbutz in 1948, the goal was only to share a slice of family history with a bit of a surprise twist I won’t give away here.

They had just sent the first couple pages of inked drawings to their colorist when Hamas invaded Israel, attacking several kibbutzim among other targets. By the time Shorr and Edelglass got those colored pages back in an email at 6 a.m. on Monday, Oct. 9, the world had changed irrevocably and so had their project.

“Our thinking about this story and its purpose and its meaning shifted,” said Shorr, a filmmaker and screenwriter based in Sharon, Massachusetts. “It’s a significance that we couldn’t have predicted, not in our worst nightmares. But there it is.”

New life for an old story, Part I

Shorr’s grandfather Jacob, a.k.a. Saba Yaacov, didn’t talk all that much about the war that followed Israel’s declaration of independence on May 14, 1948.

“Everybody knew that my grandfather had been shot in the knees during the war and that’s why his knees sometimes hurt,” Shorr said. “I didn’t really get the full story from him until my uncle sat him down over the course of many days and interviewed him on video.”

Born in Jerusalem in 1930, Yaacov was only 18 when the war broke out, but the young sabra was assigned to train new recruits, some of them Holocaust survivors. Barely a week in, Arab forces were advancing toward Kibbutz Ramat Rachel, a crucial strategic target on the path into Jerusalem. Yaacov and his men held the hilltop for as long as they could amid the heavy bombardment. When they were down to their last grenade, it was time to retreat. As Yaacov and his motley crew of soldiers ran, he was shot in both knees.

Shorr first turned to Saba Yaacov’s story from this battle — and to the care that saved his legs and life — for a short film script he wrote for an event at his shul back when he was living in Los Angeles. He called it Brother’s Keeper and Yaacov, still alive at the time, liked the Hollywood take on his tale. Though Shorr never ended up producing the film, he kept the script in his digital file cabinet of ideas. This past summer, he and Edelglass came across it as they brainstormed.

The pair met more than a decade ago at Camp Ramah New England, where Edelglass is now the co-director and Shorr came in to teach a filmmaking workshop. A few years ago when Shorr was looking to make his first foray into comics, he turned to Edelglass, who’s long kept up a side gig as a freelance illustrator. The camp colleagues ended up collaborating on José and the Pirate Captain Toledano, a graphic novel about Jewish pirates in the 16th-century Caribbean.

Back at Camp Ramah this past August, Saba Yaacov’s story caught their attention. They quickly decided: Brother’s Keeper would be their next project and they’d get a short, single-issue comic book done in time for The Jewish Comics Experience (a.k.a., JewCE) in New York City in November.

‘Just a story about a war’

Shorr plotted out the narrative and wrote a new script. Then Edelglass made rough pencil sketches for 20 pages worth of panels, scanning and sending them to Shorr piecemeal. They discussed and tweaked.

Shorr was determined to frame the story as he felt his grandfather would, without a blaring moral or message. “I wanted to make sure to hang a hat on that in a way, to make it clear,” he said. “That’s a challenging thing for any storyteller who’s trying to tell a war story — how do you make sure that you’re not cheering for war when perhaps you shouldn’t? And how do you make sure that you’re not speaking out against war when … sometimes we are forced to enter into them as a matter of survival?”

The first page of the book — and the first Edelglass inked and sent to Aljoša Tomić, their colorist in Serbia — depicts an older Yaacov sitting in a dim study in his adopted home in Lexington, Massachusetts, in the late 1990s. He’s carefully adding stamps he’s received in an envelope — including a bright yellow Doar Ivri, or Hebrew Post, stamp postmarked Jerusalem 1948 — to his collection.

“Does a war story have to mean anything?” he muses. “What if sometimes a war story has no meaning? Like my story? Just a story from a war.” He’s transported back to the hilltop in Ramat Rachel, moment and memory mixing in a poignant panel showing Yaacov still in his swivel chair pulled up to his desk, now perched on a peak overlooking a serene landscape.

Frantic as things were looking to make their upcoming deadline, with Edelglass beginning to ink about a page a day in the evening hours after his day job, they were on track. Everything was under control, if not exactly calm.

Then suddenly, Edelglass was sitting at his drawing table in the basement, inking 75-year-old war scenes while watching fresh ones flash on the news. “It was very bizarre to feel like I’m drawing this story of an attack,” he said, “as this news is filtering out and I’m absorbing over the couple days the magnitude of what had happened.”

New life for an old story, Part II

In the chaos and shock of that first week, neither collaborator immediately grasped just how much their book had changed. Not because the words or images themselves were any different, but because they would now be released in the wake of fresh tragedy and ongoing war.

A friend of Shorr’s pointed it out one night. Shorr’s wife had organized a gathering for kids to draw cards for Israeli soldiers, and Shorr happened to show some of the parents those first colored pages.

“One of my friends pointed at the screen and he said, ‘We need this. We need this now. We need this yesterday,’” Shorr recalled. “I was too close to it, I think, to see it or to recognize it,” he said. But his friend helped him realize that “this is a reminder that we’ve been here before and we’ve survived this before.”

As Edelglass kept pace with the drawings and Tomić with the colors, Shorr tried to figure out how to make the book widely available sooner rather than later. They’d bring copies to JewCE as planned, but they also made the comic available to order in hard copy online and to purchase as an e-book. Shorr is also working with his parents to translate the story into Hebrew and is looking into options for sharing Brother’s Keeper in Israel.

“There’s still some cognitive dissonance for me,” Edelglass said. “I remember the headspace that we were in as we were talking about making the story and then the headspace that we were in these last couple weeks that we’ve been completing the story. It’s almost two different universes that we’re in.”

Shorr feels that dissonance too. “It’s like a chord progression that’s not resolving,” he said. “The emotions overlap and interplay with each other. It’s an unusual experience to be recounting history and participating in it, being in the midst of it at the same time, and feeling the history and the present in this strange lockstep.”

But sitting down to draw night after night in the days and weeks following Oct. 7 was therapeutic for Edelglass. “The story moves from battle and turmoil to great hope,” Edelglass said. And he and Shorr hope it can be a source of comfort and hope for readers as well.

“It’s a story that starts off in this awful chaos of war,” Shorr said. “But somehow a sense of community, of fraternity, of togetherness, and of mutual care survives.”

There’s a striking panel near the end of the book. A nurse who helped care for Yaacov walks away from the sick beds in the makeshift field hospital that had been set up in a monastery. She’s going to write a letter to his mother to let her know he’s alive and recovering from his wounds. The hot Jerusalem sun is streaming in through an arched walkway and you can catch a glimpse of the blue sky beyond.

“Even if it’s just a story from a war, it can still mean something. It can still reassure,” Shorr said. “We see the echoes of the dark parts of the past and hope that the brighter days echo as well.”