That Bob Dylan album everybody hated 50 years ago is actually better than you’d think

Though not a masterpiece, 1973’s ‘Dylan’ is at heart, just a collection of good-time jams

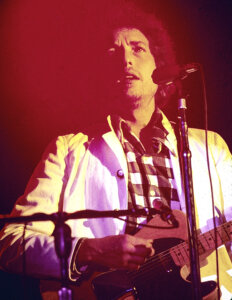

Milton Glaser’s poster art for ‘Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits,’ 1967. Photo by Getty Images

Back in 1984, Bob Dylan claimed in a Rolling Stone interview that Self Portrait, his oft-reviled double album from 1970, had been designed to scare away the sort of obsessive fans who were calling for him to retake his place at the head of “the protest movement,” and generally making his life in Woodstock and New York City miserable with their worshipful intrusions.

“And I said, Well, fuck it,’” he told the magazine. “I wish these people would just forget about me. I wanna do something they can’t possibly like, they can’t relate to. They’ll see it, and they’ll listen, and they’ll say, ‘Well, let’s go on to the next person. He ain’t sayin’ it no more. He ain’t givin’ us what we want,’ you know?”

A messy grab bag of traditional, pop and folk covers, live recordings from Dylan’s 1969 Isle of Wight performance with The Band, and Dylan originals whose perfunctory lyrics (or lack of lyrics entirely) seemed like a middle-finger salute to anyone still looking to him as a “generational spokesman,” Self Portrait was greeted as a profound disappointment upon its release. The album was widely panned by the rock critics of the day —most infamously by Greil Marcus, who began his Rolling Stone review of it with the line, “What is this shit?”

This was all part of the plan, Dylan insisted in 1984. When asked by Rolling Stone why he’d felt it necessary to make this intentionally alienating statement with a double album, he replied, “It wouldn’t have held up as a single album — then it really would’ve been bad, you know; I mean, if you’re gonna put a lot of crap on it, you might as well load it up.”

Dylan’s self-deprecating assessment of Self Portrait didn’t exactly elevate the album’s standing in his discography, and it further downgraded 1973’s Dylan LP by extension. For, according to the Dylan lore of the day, that album was a collection of Self Portrait session outtakes so bad that they’d been left to molder in the vault — at least until Columbia Records decided to release them without Dylan’s input as “revenge” for him leaving the label to sign new deal with David Geffen’s Asylum imprint. And since Dylan was just a single album of Self Portrait-related “crap,” one could conclude by Dylan’s reasoning that it must be really bad.

Released on November 16, 1973, Dylan hit the stores at a moment when Dylan buzz was at its highest in years. Word on the street was that he was working with The Band on his first “proper” studio album of new material since 1970’s New Morning, and that they would all be touring together at the beginning of the year — a nationwide jaunt that would mark Dylan’s first live appearance since 1971’s Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden, and his first actual tour since 1966. “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” from Dylan’s recent soundtrack for Sam Peckinpah’s revisionist western Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, was still knockin’ around Billboard’s Top 20, giving him his first big hit since 1969’s “Lay Lady Lay.”

As a result, the Dylan LP made it all the way to Number 17 on the Billboard 200, despite containing no original material and being roundly panned in the music press. Billboard was the most gentle in its review, allowing that it was “not a new Dylan LP per se, but is probably the closest thing the record buyer will find for at least several months and it is a creditable effort.” But most rock critics of the time responded along the lines of the Village Voice’s Robert Christgau, who gave the record an “E” grade and likened listening to it to watching the bespectacled (and infamously wild) Yankees reliever Ryne Duren pitch without his glasses.

I first heard about Dylan and its awful reputation back in the early 1980s, around the time that my Dylan fandom went from passive — my parents had played his music in the house ever since I was a kid — to active. To this day, the majority of people I’ve known who actually owned the album were either Dylan completists, or casual music fans who’d picked it up because they didn’t know any better (and/or possibly because it was usually the cheapest-priced Dylan album in the record store bins).

None of them ever played it when I was around, and I certainly never asked them to. The album continued to rack up one-star reviews over the years at places like AllMusic; this, and the fact that it remained unreleased on CD in the US until 2013 (and only then as part of the Complete Album Collection Volume 1 box set) just compounded my impression that Dylan was a record not worth bothering with.

But as with so much else about and by its creator, Dylan is a record that can’t be easily pinned down or dismissed — that is, once you’ve actually listened to it. I only finally did so about a decade back, after 2013’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 10 – Another Self Portrait (1969–1971) put the original Self Portrait in a brighter light and broader context and earned this particular Dylan period some grudging critical respect, and upon belatedly learning that Dylan was mostly made up of outtakes not from Self Portrait, but rather its wonderful follow-up New Morning.

So if the Self Portrait sessions weren’t an exercise in artistic self-immolation after all, I reasoned, and Dylan was primarily comprised of leftovers from one of my favorite Dylan albums, Dylan might actually be good for a spin or two after all…

Recorded during the first week of June 1970 as part of the same sessions that produced such New Morning gems as “The Man in Me,” “Three Angels” and that album’s title track, Dylan’s first seven cuts offer up a similarly loose and warm vibe. Backed by a sympathetic group of musicians including Russ Kunkel on drums, longtime pal Al Kooper on keyboards, future country star/Benghazi conspiracy theorist Charlie Daniels on bass, and backing vocalists Hilda Harris, Albertine Robinson and Maeretha Stewart, Dylan takes an unpretentious crack at some other people’s songs, ranging from traditional folk numbers “Lily of the West” and “Mary Ann” to Jerry Jeff Walker and Joni Mitchell’s respective recent hits “Mr. Bojangles” and “Big Yellow Taxi”.

As with the album’s remaining pair of tracks — a rocking take on the Elvis Presley-popularized “A Fool Such As I” and the cowboy ballad “Spanish is the Loving Tongue,” both recorded in April 1969 during the sessions for what would become Self Portrait — Dylan isn’t making any grand artistic statements, spiritual explorations or political prophecies with these recordings; he’s merely having a good time, enjoying the sort of life-affirming fun that millions of other musicians have experienced through the centuries while singing songs they love with similarly inclined companions. And the joy in the room — especially on Joni’s tune, the Uncle Dave Macon country blues “Sarah Jane” and the laid-back rearrangement of Elvis’s 1962 hit “Can’t Help Falling In Love” (which comes complete with Kooper’s “Just Like a Woman”-quoting organ fills) — and affection for the material is nicely palpable on these recordings.

Some Dylan reviewers have accused Dylan of intentionally sabotaging these songs, which I don’t hear at all — sure, he stumbles a bit over the lyrics of “Mr. Bojangles” at one point, but he never sounds less than engaged, or like he’s operating with any kind of agenda beyond “Let’s try recording this song and see what happens.” His take on Peter La Farge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” (a 1964 hit for Johnny Cash) might run a bit long at five minutes, but Dylan’s delivery of the lyrics — which tell the tragic tale of a Native American WWII hero who raised the American flag at Iwo Jima but descended into alcoholism upon his return home — is unquestionably passionate and sincere.

And while Dylan’s florid, Spanish guitar-laced version of “Spanish is the Loving Tongue” isn’t as interesting as the piano-forward version from these sessions that wound up as the B-side of the 1971 single “Watching the River Flow,” it’s still kind of fun to hear the Mighty Zimm go into full-on Marty Robbins mode.

Dylan is no masterpiece, but it’s still a way more intimate, inviting and enjoyable listen than, say, 1985’s Empire Burlesque or 1986’s Knocked Out Loaded. So why the many decades of hatred for what is, at heart, simply a collection of good-time jams? Is it because Dylan in “having fun in the studio” mode simply wasn’t what anyone wanted or expected from him back in late 1973? Bad feelings certainly linger to this day among fans over Columbia having released the record without his input — but Dylan himself must have forgiven this offense, considering that he returned to the label in late 1974 and remains with Columbia to this day. So maybe we should let that grudge go, as well.

“I think of myself more as a song and dance man,” Dylan famously said during a December 1965 press conference in San Francisco, and Dylan fits very snugly into that self-assessment. If you’re a Dylan fan, why wouldn’t you want to be a fly on the wall for 33 minutes and 22 seconds as the man has a ball trying some other songwriters’ material on for size? Whatever the album’s faults, limitations and cultural baggage, Dylan is still a low-key treat, and one that’s been unfairly denigrated and overlooked for far too long.