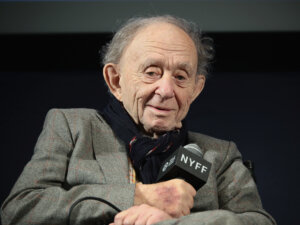

He filmed the Great American Novel — then this great Jewish filmmaker set his sights on the world’s greatest restaurant

Frederick Wiseman’s ‘Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros’ is a deep dive into a French epicurean wonder

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

At 93, Frederick Wiseman is far from your average tourist meandering through the rustic charm of Central France. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this part-time Parisian and renowned cinematic observer of institutions and society sought to express his gratitude to friends who provided him shelter near Burgundy. Armed with his trusty Michelin Guide, Wiseman embarked on a mission to discover the region’s premier restaurant — a quest that led him to the idyllic village of Ouches, located northwest of Lyon, where he found Troisgros, a three-starred culinary sanctuary acclaimed by food aficionados worldwide.

The Troisgros family, with Pierre Troisgros at the helm during the mid-to-late 20th century, has been a significant influence in French cuisine for over a century. Pierre, a pioneer of nouvelle cuisine, steered culinary practices toward a minimalist approach, moving away from the traditional, richer cooking styles like those taught at Cordon Bleu. Over the years, the Troisgros culinary legacy has evolved, with Pierre’s son, Michel Troisgros, infusing elements of Japanese cuisine into the family’s repertoire

In other words, Wiseman wasn’t checking out just any eatery; it’s a century-old epicurean wonder that has maintained its three Michelin stars for 55 consecutive years.

During Wiseman’s gastronomic odyssey, Cesar Troisgros, the fourth generation to bear the title “chef de cuisine,” made his customary round of the tables. Seizing the moment, Wiseman proposed a documentary project driven by his long-standing aspiration to capture haute cuisine’s essence. Wiseman asked if Troisgros was familiar with his work, adding that he was a filmmaker “with a not-terrible track record” and had always aspired to create a true-access documentary about a top restaurant. Cesar was intrigued by the conversation but said the final word lay with the family patriarch, Michel Troisgros. After a short hiatus, and while Wiseman was still dining, Cesar returned. “Faisons-le! Let’s do it!” he said.

“Turns out, Cesar just looked me up on Wikipedia, something I’ve never done myself,” Wiseman told me.

A self-taught filmmaker

Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries, as you might learn from Wikipedia, are masterpieces of the fly-on-the-wall American direct cinema style. This style, while sharing resemblances with cinema verité, is notably different in that it maintains the filmmaker’s invisibility within the documentary, whereas cinéma vérité often includes and acknowledges the presence of the filmmaker. Wiseman, self-taught and in company with the Maysles Brothers, D.A. Pennebaker, and Richard “Ricky” Leacock, helped to pioneer this intimate approach using synch sound and lightweight equipment.

“Wiseman is one of my heroes,” the Jewish filmmaking great, Errol Morris, told The New York Times back around the millennium. “One hallmark of a great filmmaker — Renoir, Hitchcock, Bresson, Wiseman — is to have created a body of work, a cosmos. Give up that old distinction between documentary and feature film. Call it what it is: a vision, a simulacrum of the world. No one has exceeded in scope and intensity the simulacrum that Wiseman has given us.”

After Wiseman met Michel and Cesar Troisgros for a long talk, he moved into a bed and breakfast “two minutes away” and shot for seven weeks. Before the digital age, Wiseman shot on film and then self-edited on a machine called a Steenbeck – but in his later years, he has adapted to digital Avid editing. In an industry where three years is a super-fast turnaround, he makes one film a year. Although he must fundraise like any creative and has faced numerous rejections, Wiseman has come to rely on PBS as a consistent funding source. To keep costs down, he takes on multiple roles, including directing, producing, sound and editing.

Born on Jan. 1, 1930, during the early part of the Great Depression, Frederick Wiseman grew up in Brighton, on the western edge of Boston. His father, Jacob Leo Wiseman, was a survivor of the pogroms near Kyiv, Ukraine, who arrived in the U.S. as a five-year-old in 1890. (Quick refresher: Violence against Jews escalated following the 1881 assassination of Tsar Alexander II. Despite no involvement from the Jewish community in the assassination, baseless accusations against them led to widespread violence, particularly in areas like Kyiv.)

This history of flight and continued resilience against prejudice deeply colored the Wiseman family narrative. “Yankees dominated the professional landscape in those days, including the top law schools and major hospitals, where Jewish presence was notably absent,” Wiseman told me. Despite these barriers, Wiseman’s father, Jacob, distinguished himself as a lawyer, graduating from Boston University Law in 1908 and becoming Assistant Attorney General of Massachusetts. He was on the brink of becoming the first Jewish judge on Boston’s municipal court until his nomination was upended by a Jazz Age resurgence of antisemitic sentiment.

A dreamer and a loner

Wiseman’s mother, Gertrude Leah Kotzen, a descendant of Polish Jews, was born in 1899 in Chelsea across the Mystic River. At 17, Gertie won a scholarship to the American National Theater Academy, but her mother, Ida, made her turn it down. Her thwarted ambition to become an actress — as she was pressured to pursue law at Boston College instead — became poignant family lore.

She went to Boston College and planned to go to law school, but accepted a job as a law firm secretary. Later, she managed two summer camps in New Hampshire for impoverished children and was an administrator of the psychiatric ward of the James Jackson Psychiatric Children’s Center in Roxbury.

In a 1942 “Woman of the Month” feature in the Boston Traveler, Gertrude “Gertie” Wiseman is described as known around Beantown for her love of “large hats,” engaging with Jewish culture, scouring antique shops for glass and rare china, reading biographies, appreciating colonial architecture, and hiking and mountain climbing. A 12-year-old Frederick pops up — “You’re as nice as Lana Turner, but not quite so good-looking,” he says.

“Not being able to study acting was her life’s regret,” Wiseman told me. “No matter what she accomplished, it still pained her that in my grandmother’s eyes, acting was like being a whore. But she was a marvelous actress and spoke to me in many accents and had a love for theater and the arts.”

In Fred Wiseman’s childhood home, Yiddish was as common as the Forverts on the kitchen table. He had a mostly-secular American “Passover and High Holidays” Jewish childhood, he said, and baseball interested him far more than Hebrew School. He was an only child who served as a self-appointed unofficial Red Sox statistician, memorizing baseball scores back to the 1890s for anyone willing to listen.

“My experience as a Jewish boy was very similar to the world described in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America,” Wiseman told me, “But think Boston instead of Newark. But the same prejudice, namely antisemitism, and awakening to it remained constant.”

Wiseman says he spent his early years being a “dreamer and a loner,” qualities that became a characteristic of his documentary work in which he seeks to disappear while filming. He found comfort and inspiration in comedies starring the likes of the Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Laurel and Hardy. The socially conscious humor of Preston Sturges’ films, such as Sullivan’s Travels and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, resonated deeply too.

His bar mitzvah was smack in the middle of World War II at Congregation Kehillath Israel, a conservative synagogue in Brookline; in between haftorah practice, he often listened to stories about battles on the radio. He still remembers and feels haunted by hearing Hitler’s fascist speeches. “I couldn’t understand the German; the words weren’t translated, but the hypnotic power of his voice stuck with me,” he said.

A Jew at Williams

At 17, Wiseman graduated from Boston Latin, a public school that was founded in 1635 and is the oldest existing school in the United States. He was excited to be accepted to Williams College, but when he got there, his excitement soon turned to disillusionment during fraternity rush week, when he learned that the college’s social scene was dominated by fraternities that were often off-limits to Jewish students.

“It was like being hit with a bulldozer,” Wiseman said. “You have no idea how brutal and painful it is to find out everyone hates you simply for being a Jew.”

The college’s Garfield Club, named after America’s 20th president, James Garfield (who was assassinated on his way to a Williams reunion), served as a common dining hall for those not selected by any fraternity. It was, Wiseman said, “the dumpster for everyone who didn’t get in — it allowed the college to maintain the facade in its literature that everyone belonged to an eating club.”

The Garfield Club became a refuge for Jews and other outcasts, and there, Wiseman found some of the most exciting and intelligent people on campus, who became lifelong friends. He majored in English and political science, and channeled his growing insights and frustrations into the school newspaper, where he wrote editorials condemning the fraternity system’s entrenched antisemitism.

Students at Williams College are prohibited from joining or participating in fraternities throughout their tenure at the institution. This policy, established in 1962, owes much to the activism of Jewish students such as Wiseman.

Wiseman graduated from Williams in 1951, unsure of what he should do next. He went to Yale Law School partly because, “My father liked the idea of my being in law school.” It was also a way to delay military service when the Korean War was raging; after acceptance, he got a deferment for three years, although he went into the reserve.

At Yale, he met Zipporah Batshaw, known affectionately as Tzippy or Chippy, who became his lifelong partner. Chippy hailed from Montreal, and was among the rare women to earn a law degree from Yale in 1954. The couple tied the knot in 1955 at Shaar Hashomayim, Canada’s oldest and largest traditional Ashkenazi synagogue.

After his Yale graduation, Wiseman spent 21 months in the Army, working as a sound man at Fort Dix. Completing his service in 1956, he moved to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, courtesy of the G.I. Bill. Living modestly near the Luxembourg Gardens for less than $150 a month, he was joined by Chippy for a significant part of his Parisian adventure.

Early forays into filmmaking

In Paris, Wiseman went to the movies four or five times a week, watching films by Truffaut, Fellini, and Jean Renoir. “I dreamed of writing the Great American Novel without a word. Basically, I was just hanging out,” he said. “I did all the typical things a would-be writer might do — I strolled around, sat at the same cafes, browsed Shakespeare & Co., and read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, Fitzgerald and John Dos Passos. Absolute clichéd things.”

He would also walk around with an 8-millimeter camera following his wife, and made his first trial film about a shopping street in Paris.

After two years, he returned to the United States to teach law at Boston University, then left after he got a Russell Sage fellowship at Harvard. Then, as Frederick Wiseman neared what he termed “the witching age of 30,” he felt an urgent need to discover his true calling — a quest that led him to embrace documentary filmmaking as a second career.

“When I started, I was 36, a bit older than most people,” he said.

Wiseman’s first meaningful foray into filmmaking was in 1965 as the producer of Cool World, a feature film set in Harlem that spotlighted drug addiction, violence, and deep-seated societal misery against a backdrop of racial prejudice.

Wiseman took the director’s chair for the first time with his next project, the groundbreaking documentary Titicut Follies, filmed in 1967. This film marked the beginning of his exploration of American institutions, exposing the harsh conditions at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Bridgewater. Its frank portrayal of inmate treatment sparked controversy and legal challenges, resulting in a ban on public screenings that lasted until the 1990s.

In 1971, the year his father passed away at 85, Wiseman formed a pivotal partnership with NYC’s PBS station, WNET. Committed to producing one film per year, he delved deep into the workings of institutions rather than individuals. These stories, woven together, represent Wiseman’s cinematic version of the Great American Novel. Among his most significant American documentaries are Public Housing (1997), exploring a Chicago housing development, and State Legislature (2007), which offers an inside look at the Idaho Legislature.

While best known for his work on American soil, Wiseman has also demonstrated a notable fascination with France, as seen in films such as La Comédie-Française ou L’Amour Joué (1996), which explores the world’s oldest continuous repertory theater; La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet (2009); and Crazy Horse (2011), offering an intimate look at the famed Parisian cabaret club.

In Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros, Wiseman explores a new and accessible direction within his oeuvre. This culinary documentary offers a marvelous escapism from tumultuous times, taking viewers on a four-hour journey into the heart of a bustling high-end kitchen. Here, Wiseman applies his observational style with a practical zoom lens, deftly capturing the kitchen’s rhythm and nuances. The film begins at the market — for Wiseman, every culinary journey starts there. His meticulous editing approach ensures that the film is every bit as compelling as it is comprehensive.

Wiseman today

After a marriage spanning more than six decades, Wiseman’s wife Chippy passed away on Jan. 20, 2021. Despite this profound loss, he remains committed to filmmaking, viewing it as an integral part of his identity and a means to stay engaged and active. He’s finalizing the digitalization of his earlier films and gearing up for his next project.

Wiseman today relishes simple pleasures like leisurely walks and immersing himself again in books. He continues the cherished family traditions he enjoyed with his late wife and mishpocha, still gathering in a cozy lodge in the Alps for Christmakkah. There, he enjoys getting warm by the fireplace and sipping hot chocolate with his two sons, their partners, and his three grandchildren as they return from the slopes. Additionally, he remains deeply engaged with issues related to Israel, worried sick about growing tragedy in the world but proudly embracing his progressive Jewish heritage.

The film Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros premiered at the Venice Festival, was featured at the New York and Toronto film festivals, and will open Nov. 22 at Film Forum. It will be the 16th of Wiseman’s films to debut there, making him the most-premiered filmmaker in the theater’s 53-year history.