A Jewish artist so gifted, he could even teach a stone to paint

The ever-evolving impressionist Camille Pissarro is the subject of Anka Muhlstein’s latest book

A visitor views an 1894 painting by Camille Pissarro. Photo by Getty Images

Camille Pissarro: The Audacity of Impressionism

By Anka Muhlstein

Translated from French by Adrianna Hunter

Other Press, 320 pages, $30

The Rothschilds were the royalty of European Jewry, so it was only natural that, in Baron James (1981), Anka Muhlstein was drawn to write about the consequential founder of the French branch of the family, James de Rothschild — especially since he was her own great-great-grandfather. Now, more than 40 years later, after books on Napoleon, Elizabeth I, Proust, Balzac, and others, as well as 2009’s Venice for Lovers, which she co-wrote with her husband, Louis Begley, Muhlstein takes on artistic royalty, Camille Pissarro. He also happened to be Jewish.

More than half a dozen studies of Pissarro — including one by Joachim Pissarro, the painter’s great-grandson — have been published in just the past 20 years. But what Muhlstein declares drew her into this biographical scrum is the artist’s “sense of being apart, different, and hard to classify.”

Although Paul Cezanne dubbed him “the father of impressionism,” and impressionism would become the most popular artistic movement of modern times, Pissarro always felt himself an interloper. He was born in 1830 in the Caribbean, on the island of St. Thomas, which was then controlled by Denmark, making him a Danish citizen. That complicated his longtime residence in France, especially when the Franco-Prussian War — in which more than a thousand of his paintings were destroyed — erupted in 1870, and he temporarily relocated to England. Though buried in Paris in 1903 in the legendary cemetery Père Lachaise, the great French painter was not French.

However, he was certainly Jewish, on both sides of his family, and disdain toward Jews was commonplace in Paris, where he settled in 1855. Pissarro never ceased to consider himself Jewish, although Muhlstein notes that he behaved “like all dejudaized Jews for whom the cult of republican values had replaced any religious practice.” He scandalized his parents by marrying Julie Vellay, a Catholic who worked as his mother’s kitchen maid, and the couple had seven children together. Even so, Pissarro’s mother never accepted the marriage.

Later, during the Dreyfus Affair, when a Jewish French army captain was condemned to Devil’s Island on spurious charges of espionage, Pissarro eventually joined others in opposing the blatant injustice. The case aroused widespread, virulent antisemitism, and Pissarro feared that all Jews might be deported from France. However, he observed the tenets of classical anarchism more faithfully than those of halakha. A bit fuzzy on his theology, Muhlstein claims Pissarro held “agnostic views,” but then, two pages later, refers to him as “an atheist.”

No doubt recognizing that Pissarro’s outsider Jewishness is too frail a thread with which to weave an entire book, Muhlstein, whose French text is translated by Adrianna Hunter, pivots to a more fruitful thesis, that “painting and bringing up his children constituted the twin poles of his existence.” She offers vivid accounts of Pissarro at work — en plein air, often alongside fellow artists who became close friends. He met regularly with Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Frédéric Bazille, Alfred Sisley, and Berthe Morisot and later drew Paul Gauguin, Mary Cassatt, Gustave Caillebotte, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac into his orbit, both teaching and learning from them.

Pissarro, who defined an impressionist as “a painter who never produces the same picture twice,” has a less distinctive brand than Monet, Renoir, or Cézanne because of his willingness to evolve, even experimenting with pointillism, to the dismay of earlier comrades. Yet the chameleon Camille was the only artist to show at all eight of the impressionist exhibitions (though Muhlstein states that “he alone with Degas participated in every impressionist exhibition,” Degas was an organizer but did not, in fact, show his work in all of them).

Drawing on a rich body of Pissarro’s letters to his oldest son, Julien, Muhlstein paints a portrait of a loving, devoted father. Cassatt observed that “Pissarro is such a good teacher that he could teach the stones to paint properly,” and the proof is not only in his influence on her work but also in the fact that three of his sons became reputable painters, as did a granddaughter, a grandson, and a great-grandson.

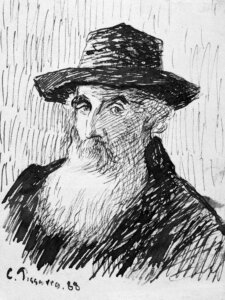

It was only in the final years of his life that Pissarro’s paintings began to sell, lifting him and his family out of poverty. Muhlstein examines the intricacies of the 19th-century art market and the role played by the wily dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in promoting impressionism. With only five reproductions and cursory descriptions of the paintings, Muhlstein is less interested in providing analysis of Pissarro’s art than presenting a portrait of the artist as an innovative and beneficent bundle of energy. With his long white beard and irrepressibly youthful interest in everything, he was a beloved figure to his contemporaries. It is hard to resist the Jewish outsider who wrote to his son Lucien: “Painting, art in general, enchants me. It is my life. What else matters?”