Why Siskel & Ebert were the Talmudic scholars of their day

As a new book explains, the film critics famously disagreed, but never disparaged

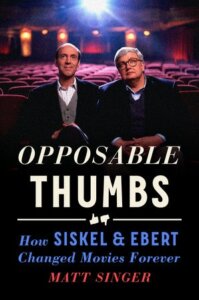

Film critics Gene Siskel, left, and Roger Ebert at the National Association of Broadcasters Convention in 1986 in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo by Norm Staples/Getty Images

I have two friends, one on the left side of the political spectrum and one on the right. We disagree on many issues. But in spite of that, our friendship has endured for decades. Why? Because we know that each of us is sincere and thoughtful in defending our positions. In the final analysis, we respect one another. We can disagree and still be friends. In the world of film criticism, Gene Siskel and Ebert personify that kind of competitive but civil relationship.

As a film aficionado, I have always admired the thoughtful movie reviews of Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert. I regularly watched their conversations on television and devoured the new book by Matt Singer titled Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel and Ebert Changed Movies Forever.

Celebrated for their honest and stimulating critique of films, their debates reminded me of the arguments between two of the Talmud’s foremost scholars, Hillel and Shammai. Like them, Siskel and Ebert were contrary personalities. Perhaps due to their varied life experiences, they saw things differently when it came to evaluating movies. However, in spite of those differences, they respected one another’s viewpoint and carefully listened to each other’s arguments. Ego alone did not drive the conversation. Artistic truth did.

In the Talmud, we find a similar style of debate. Many Talmudic sages do not share the same opinions, and they robustly challenge the other’s viewpoint on a particular subject. For example, Hillel and Shammai disagree with one another, but disagreement does not mean disengagement from the other. In spite of seeing things differently, they respect the other’s opinion even when it veers from their own.

A classic example of their different approaches relates to how they responded to a would-be convert to Judaism. The convert first went to Shammai, asking him to teach the entire Torah to him while standing on one foot. Shammai chased him away. The convert then went to Hillel and asked the same question. Hillel told him: “What is hateful to you, don’t do to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah. The rest is commentary. Go and learn it.” Differences between them may exist on one topic, but the conversation between the Sages continues on other subjects.

Moreover, the Talmud records that the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel did not refrain from intermarrying with one another. They practiced affection and camaraderie with one another in spite of their different intellectual approaches to a problem.

Alternative approaches and opinions certainly occur in the Talmud, but they do not result in name-calling or casting of aspersions on the other’s integrity. What is paramount is objective analysis that leads to reasonable conclusions.

Moreover, Siskel and Ebert went beyond analyzing a film’s acting, editing or cinematography. They often brought in life lessons: For example, a discussion of the 1989 movie My Left Foot, starring Daniel Day-Lewis as a quadriplegic painter, morphed into a conversation on how people cope with family members who are disabled.

Living vicariously

Roger Ebert reminds us of the reason we go to movies: “To have a vicarious experience,” he said while giving advice to young movie critics. “We stop being ourselves to some degree and become the characters on the screen.”

Ebert’s sentiments echo my own. I remember growing up in the small town of Mt. Vernon, New York, and going to the movies after attending synagogue on Shabbat morning. The movies took me to faraway places. I still vividly recall the vast open spaces that I saw in Shane, a classic Western of the 1950s starring Alan Ladd. I emotionally identified with the hero, and hated the villain played by Jack Palance in one of his iconic roles.

In recent years, I have discovered a side benefit of watching movies. It keeps me from engaging in lashon hara, slander and gossip. I can say anything I want about the characters in a film and it does not hurt them. Why? Because the characters I discuss do not really exist. They may be based on real people, but, in the end, they are merely figments of the creative imagination.

Siskel and Ebert’s discussions about characters, their deeds and motivations, form the core of the crosstalk between them. Indeed, the characters in the story become catalysts for serious discussions about the nature of life itself.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Should Diaspora Jews be buried in Israel? A rabbi responds

-

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.