A ‘heartbroken’ Palestinian author confronts his prominent father’s murder, a history of international betrayal and devastation in Gaza

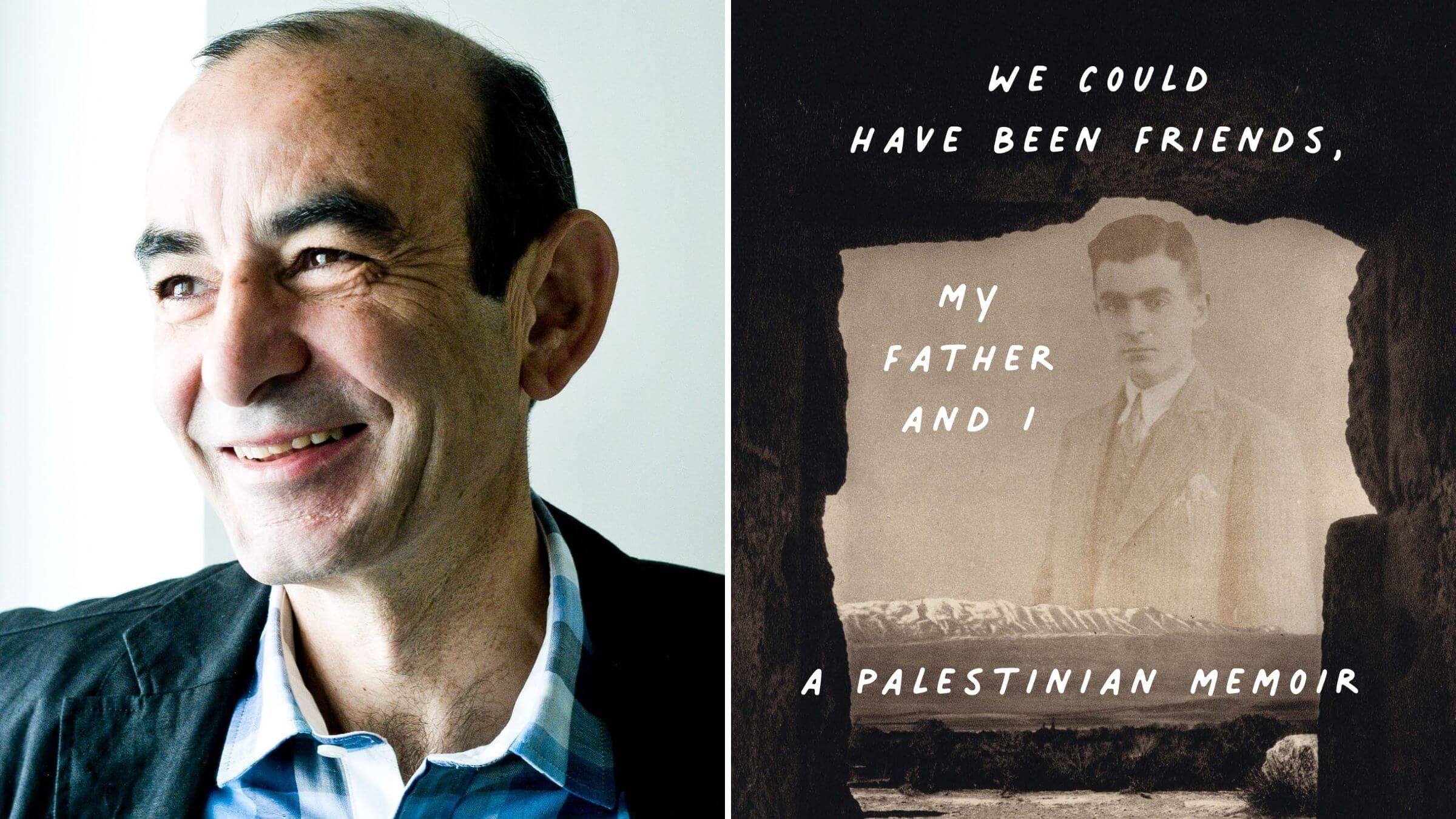

Raja Shehadeh and his father, Aziz, emerged as leading Palestinian lawyers in their generations. A new book explores their different approaches to challenging the Israeli government — and the personal cost of their shared vision.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The lawyer and author Raja Shehadeh’s professional path looks a lot like his father’s.

Both men emerged as leading Palestinian lawyers of their respective generations. The elder Shehadeh, Aziz, was an early proponent of using legal methods to challenge the actions of the Israeli government; his son founded Al-Haq, a prominent West Bank human rights organization. Aziz, who was murdered in 1985, kept a meticulous personal archive of his writings, correspondence, and cases; Raja has published several memoirs.

Despite devoting themselves to the same goals and even working together for many years, the two men maintained an emotionally distant relationship, unable to appreciate each other’s professional success or political commitments. That disconnect is the subject of the younger Shehadeh’s most recent memoir, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, a recent finalist for the National Book Award, in which the author investigates Aziz’s life and career as he never could during his father’s lifetime.

Relying on the archive and his own imagination, Shehadeh sketches a portrait of his father’s cosmopolitan upbringing in mandate-era Jaffa, his displacement to the West Bank during the Nakba (the Arabic term for the mass displacement of Palestinians during the creation of Israel) and his legal activism. Because Aziz quickly emerged as a refugee leader, his story provides a unique window into the earliest debates over what a Palestinian national future might look like. Aziz found himself fighting not only Israel but also Jordan, itself a newly created state whose Hashemite monarchs, Shehadeh argues, acquiesced to Palestinian dispossession in order to gain control over the West Bank after 1948. For his insistence on Palestinian statehood and democratic processes in Jordan, Aziz paid with a period of imprisonment in the country’s notoriously inhumane Al Jafr prison.

For readers who take up We Could Have Been Friends, as I did, after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, the memoir can serve as both textbook and warning, outlining the history of legal challenges to Israel’s occupation at a time when political solutions seem more distant than ever. I interviewed Shehadeh, who lives in Ramallah, over email. We talked about the work of imagining his father’s life, the lessons his memoir can offer readers today, and the “profound fear” he’s experienced since Oct. 7. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What has your experience been like in the past six weeks, as someone watching the bombardment of Gaza from within the West Bank?

Answering numerous emails asking how I was doing, I noticed that the word that was repeated in the course of my responses was “heartbroken.” There was a moment on Oct. 7, after I first heard about Hamas fighters breaking through the barriers, when I felt optimistic. These were the barriers that for the past 16 years had kept the Gaza Strip under a blockade, restricting the residents’ mobility and limiting their chances for development and decent living. It was like watching the unjustly imprisoned anywhere break their chains and escape their incarceration. Perhaps this might dispel the notion that fortifications, however formidable, can bring security for Israel. That was before I learned about the indiscriminate killings of Israeli civilians and soldiers that Hamas had committed in the course of its bold operation.

As I witnessed on television the utter devastation Israeli bombardment has caused in Gaza, and saw one building after another collapsing on civilians sheltering there and leaving thousands under the rubble, I found myself unable to imagine the scope of the suffering of the people of Gaza. When I witnessed the Israeli army’s attempt to push residents of the north to the south, creating further suffering, I feared that Israel was preparing for the total or partial ethnic cleansing of the Strip and the creation of another Nakba similar to that which Palestinians endured in 1948.

I also wondered how the Israeli public was reacting to the actions of its citizen army. I remembered the huge Israeli demonstration that took place after the Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982. This protest led to the creation of the Kahan Commission, and eventually to the resignation of Ariel Sharon, then the minister of defense. I was aware of the Israeli anger and revulsion at what Hamas had committed on Oct. 7, but the main victims of the bombardment in Gaza were civilians. I contacted some of my Israeli friends, who said there was massive support for the attack on Gaza, and little concern or empathy for the Palestinian victims. One friend added that any expression of horror or criticism is taken as disloyalty. He said that while he always felt in a minority, he now feels he is in a minority among a minority of a minority.

I later learned that the Israeli media was not exposing their public to the devastation that the bombardment was causing to Gaza. The Arabic media also did little reporting on the suffering of Israeli families who had hostages trapped in Gaza. When I saw some of the older women Israeli hostages being freed by Hamas, the suffering their families must have endured was brought home to me. What a tragic aspect of this struggle, that civilians should end up being used as bargaining chips. Now that the short pause in the fighting has ended, as did the hostage release, the anxiety and suffering of all the Israeli families who still have hostages with Hamas will continue.

Closer to Ramallah where I live, violent settlers have taken advantage of the situation to commit daily rampages, attacking olive pickers and cutting hundreds of trees belonging to Palestinians. The attacks taking place in the West Bank by both the Israeli army and Jewish settlers have led to the deaths of some 240 Palestinians.

This book focuses on the betrayal of Palestinians by Arab states, especially Jordan. How do you see the legacy of those betrayals manifesting today?

Now, more than five decades after the events I described in the book, conditions are entirely different. Those who experienced the betrayal are almost all gone, and the knowledge of this period among the generations who came after is scant. This was evident from the reaction to my book among many readers here, who told me they previously had no idea about Jordan’s historical role.

Today, however, Jordan is standing firmly against the prospect of Israel carrying out another Nakba — and as such, is proving a true supporter of Palestinians.

You rely on your father’s correspondence and writings to interpret his professional and political activities. What resources did you draw on to imagine his inner life — for example, during his imprisonment in Al Jafr?

I relied mainly on my imagination and memories of conversations we had when I worked alongside my father in his law office.

For Al Jafr, I relied upon a memoir written by one detainee who was there at the same time as my father. Most important of all was the field visit I took to the prison’s site in Jordan. I tried to put myself in place of my father as he endured the harsh desert conditions there.

You write about the difficulty of interpreting political crises in the moment, citing your father’s inability to comprehend the consequences of his 1948 expulsion and your own experience in the immediate aftermath of the 1967 occupation. Do you think this is happening today? How should people attempt to think through the violence we are seeing now?

Nowadays there is more political awareness among the Palestinian public than ever. Social media and networks of young activists have played an important role in informing the public about what the establishment media tries to suppress. Yet to a large extent each side, Palestinian and Israeli, remains confined in its own worldviews and prejudices.

For me, and a limited number of people among the two nations, the irrefutable fact is that at some point in the future we must coexist and live in peace in a shared land. Neither the destruction of one people by the other, nor ethnic cleansing, will ultimately succeed. If this is taken as the long-term goal, one can evaluate today’s events using that yardstick.

You portray your father as swimming against the tide of his generation in his focus on using the law to resist Israeli occupation. How might history have gone differently, particularly in the negotiation of the Oslo Accords, if his tactics had been more widely embraced?

My father was a top lawyer in Jaffa under the Palestine Mandate, and later in Jordan after 1948. In the memoir, I describe a few of his precedent-setting cases, one of which is the case of the “blocked accounts.” In 1948, Israel froze Palestinian accounts in branches of Barclays Bank under its control, refusing to allow refugees to access their money. My father succeeded in forcing Israel to release those funds.

I can only suspect that my father would have been appalled at the lack of legal preparation and grounding for the Oslo negotiations and the carelessness of Palestinian negotiators to the legal aspects of the agreement that resulted. Because the Oslo Accords did not ban settlement expansion in the occupied territories, Israel was able to continue violating Palestinian land rights.

Oslo ended up a missed opportunity for arriving at a durable peace. After it was signed the number of illegal Jewish settlers living in the West Bank quadrupled, eroding the prospect of establishing a Palestinian state alongside Israel, which my father had called for.

Like your father, you devoted yourself to challenging the occupation through the law, but you write that settlement expansion has transformed the West Bank far beyond what you imagined in 1967. Have your feelings on the role of lawyers in the Palestinian liberation movement changed over the course of your career?

Until I read the agreements signed in 1993 and 1995 between Israel and the PLO, I thought we could stop settlements by exposing how they violated local and international law. After the Oslo Accords, settlement expansion continued at a faster pace than ever. This failure of legal negotiations to bring an end to the illegal settlements marked the defeat of the project I had dedicated my life to.

The Israeli army’s current excesses in killing innocent Gazan civilians in the course of its war on Gaza stem from the failure to legally challenge crimes it committed in previous rounds of fighting. Whether the International Criminal Court will investigate and charge all those committing war crimes — on behalf of Hamas or Israel — is yet to be seen. If that happens, my belief in the efficacy of international law will be revived.

You’ve written about your father in your first memoir, Strangers In the House. What made you want to take up that relationship in a new book, and how did you decide to use his archive as the memoir’s central construct?

Writing about my father in Strangers in the House, and about my failure to persuade the Israeli police to investigate his murder, was emotionally draining. It took many years before I could think of writing again about my relationship with him.

Just as I was setting off to write a different book, a friend brought me a photocopy of the Palestine Telephone Directory of Jaffa-Tel Aviv from January 1944. There I found my father’s office number, and that of my grandfather, Judge Salim Shehadeh. Emotion overwhelmed me. All that history of their life in Jaffa is denied, just as my father’s history of political activism on behalf of Palestine has been erased. This was the catalyst — I was slowly getting ready to open that cabinet where I kept my father’s files, and look inside.

My father’s legacy as one of the first Palestinian leaders to propose a Palestinian state next to Israel is not well-known. I wanted to write about that, as well as his sincere belief that the only real victory is when we both, Israelis and Palestinians, win. How far we are from this today.