‘I have my own planet’: An Argentine Jewish artist makes a psychedelic, exuberant US debut

The Jewish Museum’s latest exhibit, ‘Marta Minujín: Arte! Arte! Arte!,’ is a joyful survey of a 1960s icon

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Editor’s note: All artwork titles in this piece have been translated into English from Spanish.

Manhattan’s Jewish Museum just got a lot groovier.

Its new exhibit, Marta Minujín: Arte! Arte! Arte! — the Argentine artist Marta Minujín’s first-ever survey exhibition in the United States — is a technicolor time machine, recalling the radical optimism and fluorescent palette of the 1960s.

The show, which features some 100 items spanning Minujín’s 60-year career, bursts with color and whimsy, capturing Minujín’s remarkable ability to imbue her art with social critique while maintaining a childlike glee.

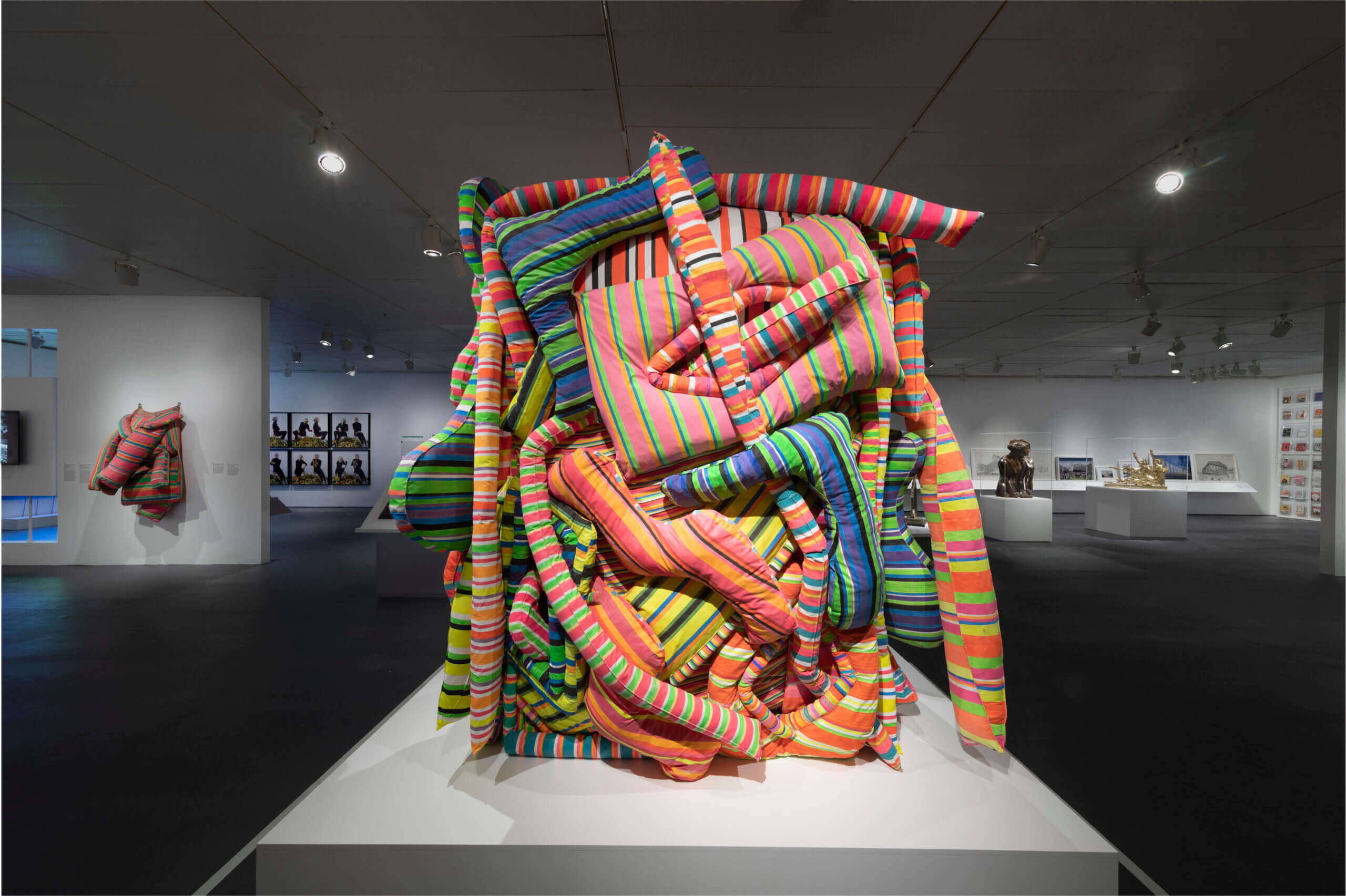

The exhibit is dominated by Minujín’s mattress-based soft sculptures, perhaps her most enduring symbol. The artist’s self-described “love affair with mattresses” began in Paris in the early 1960s, when she first began to fashion mattresses into artworks.

The brightly striped mattresses, which Minujín deconstructs and stitches into abstract, mind-bending formations, “are a constant in my work,” she said in an interview before the exhibit’s opening. “We spend half of our lives on mattresses. We are born on one, and one day we will most likely die on one.”

In 1963, Minujín piled up three years’ worth of mattress art in an empty lot in Paris’ Montparnasse district, then filmed herself and fellow artists burning it all to the ground. In the exhibit, excerpts from that film, titled The Destruction, play on loop. “Why … was I going to keep my work?” Minujín said, discussing her decision to make The Destruction. “So that it could die in cultural cemeteries, the eternity in which I had no interest? I wanted to live and make others live.”

Luckily, the atmosphere in the Jewish Museum exhibit is closer to a psychedelic slumber party than a cemetery. A few rare examples of mattress art that survived her 1960s bonfires are presented alongside newer sculptures in the same mode. “I started with mattresses in the ’60s, but then I stopped for 40 years, and then I started again in 2007,” Minujín said. “I went back to my roots.”

Also on display are numerous conceptual sketches for the mattress sculptures, which are fascinating works in their own right. Minujín works in bold, quick strokes that writhe and squirm, depicting twists and turns that seem impossible to replicate in three dimensions.

But Minujín’s oeuvre encompasses far more than mattresses, and Arte! Arte! Arte! does an admirable job of giving context to her vast catalog of performance art. The exhibit includes video of her hijacking a 1965 live broadcast on Argentine public access television with a stampede of horses and bodybuilders, and, a few months later, dropping 500 live chickens from a helicopter onto a football stadium in Uruguay. In the 1983 piece Parthenon of Books, photographs of which are displayed in the exhibit, Minujín reconstructed the ancient Parthenon temple in her native Buenos Aires using 20,000 books that had been banned during the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976–83.

The work became a symbol of the restoration of democracy to Argentina — and, fittingly, when it was disassembled after five days of exhibition, the books were distributed amongst the public.

Alongside the mattress sculptures, standouts from Minujín’s visual art include the gorgeous 1973 Frozen Sex paintings. Minujín was inspired to create the series after spending time exploring the pornographic cinemas and sex shops of Washington, D.C., as well as befriending a sex worker who served high-end clientele in New York City.

Minujín’s work had sexual undertones from the beginning, but in Frozen Sex, her fascination with sexual imagery found new creative expression. Despite the focus on genitalia, these oversize paintings never veer into pornography. Rather, their abstract forms and flat color fields allow viewers to fill in their own details, combining Minujín’s bold pop aesthetic with a calming palette that recalls the intimate shadows of a bedroom. Cloistered away in an enclosed corner of the gallery, the exhibit’s most brazen material becomes a kind of meditative refuge.

A particularly outstanding painting from the series is Freezing throughout (self-portrait from the back), which depicts a nude woman lying on her side, viewed from the back. The painting is horizontally bisected between the dusky pink background and the burgundy surface on which the woman, presumably Minujín, is lying, as well as between the two halves of her body. The effect almost creates an illusion of two people lying intertwined, before the mind rights itself and pieces the elements into a single whole.

Minujín’s most recent series of paintings is just as radical. Entitled Pandemic/Endemic, three enormous collages were selected for display from the series, which Minujín made between 2021 to 2023. Each composed of thousands of tiny strips of fabric, these are the sorts of paintings one can get lost in: the scale of the canvases contrasted with the miniscule strips creates an oceanic effect, an illusion of movement.

In addition to the exhibition, the Jewish Museum teamed up with the public arts program Times Square Arts to present Minujín’s 30-foot inflatable Sculpture of Dreams. Described by Minujín as an “anti-sculpture,” the piece is her first public sculpture in New York and one of the largest installations ever placed in Times Square. The 16-piece spectacle invites visitors to enter its colorful interior and whisper their hopes and dreams into hidden speakers before exiting, all while recordings of birdsong play. Amorphous, striped forms give the sculpture a soft, pillowy quality that evokes the artist’s beloved mattresses at an extraordinary scale.

The installation is simultaneously personal and remote, soliciting intimate secrets in one of the most crowded and alienating places on Earth. It’s playful but thoughtful, irreverent yet sincere — and totally Minujín.

While Sculpture of Dreams is a striking work, it may not seem particularly groundbreaking; after all, we live in an age of Instagram-tailored pop-up art exhibits, where eye-catching color and scale abounds. But the Jewish Museum’s exhibit gives a fuller picture of Minujín, revealing her startlingly prescient awareness, dating back to the early 1960s, of the ways immersive experience can engage audiences. Her present work, delightful on its own, has added dimension when viewed in the context of her lifelong obsession with kaleidoscopic color and fierce originality.

At the press preview, Minujín was asked by an audience member whether she saw her Jewish identity as having any bearing on her work. Minujín seemed perhaps a little confused by the question; she paused for a moment, then finally shook her head. “I have my own planet,” she replied.