Auschwitz would seem an unlikely backdrop for a love affair, yet this is a true story

Keren Blankfeld’s ‘Lovers in Auschwitz’ tells of the relationship between David Wisnia and Helen Spitzer

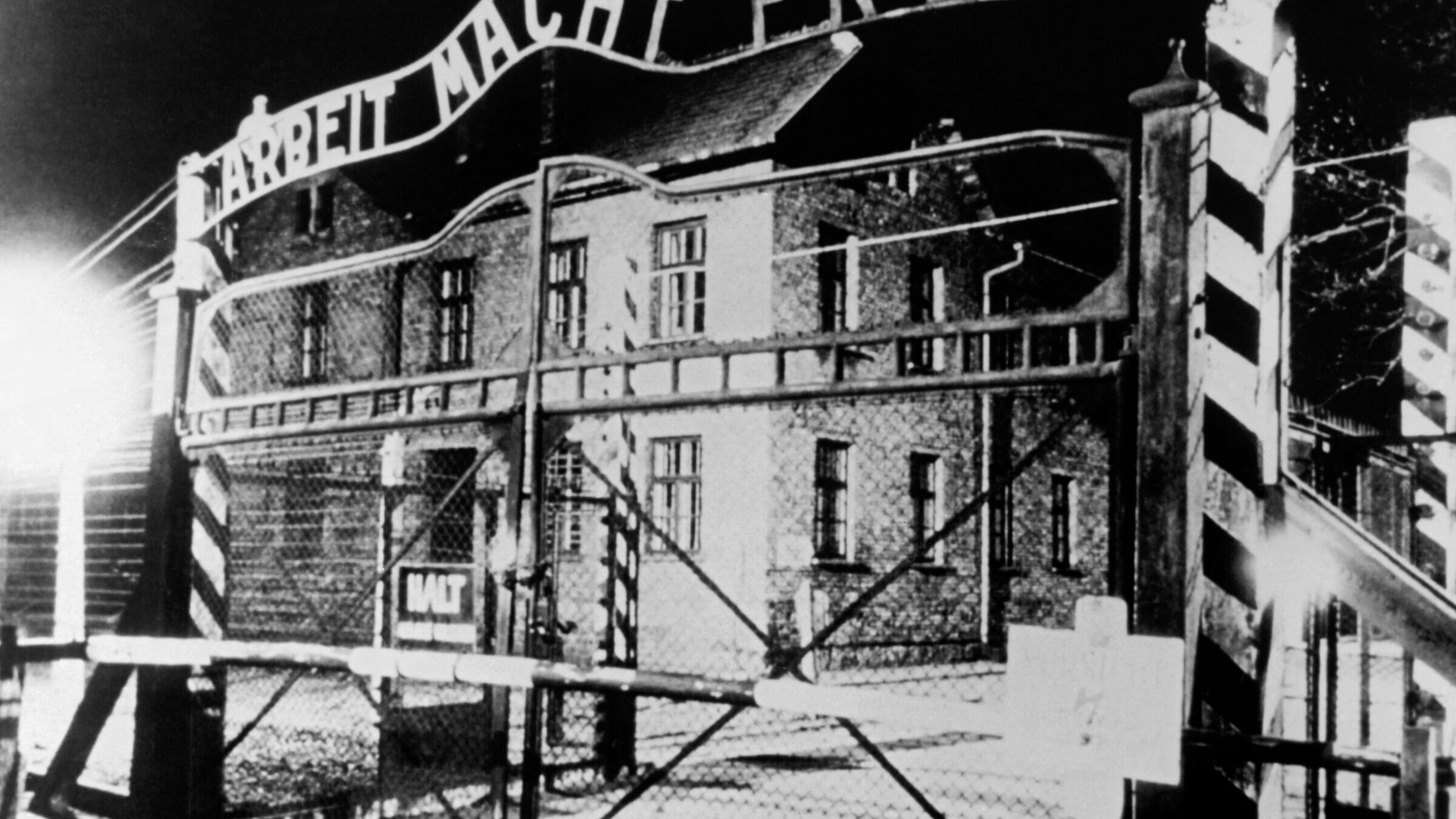

Picture taken on January 1945 at Auschwitz. Photo by Getty Images

Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story

By Keren Blankfeld

Little, Brown and Company, 400 pages, $32.50

For 1.1 million people, nearly a million of them Jews, Auschwitz-Birkenau was a graveyard. For countless others, this most notorious of Nazi concentration camps was a surreal hell of starvation, torture, forced labor and disease — a place where, as one guard famously told the Italian memoirist Primo Levi, “there is no why.”

Over the years, survivors have added nuance to this portrait. We know that an underground camp resistance simmered, finally erupting into revolt; a privileged status could make life marginally more bearable; music served as both salvation and torment; and even love, of a sort, was possible.

Keren Blankfeld’s gripping Lovers in Auschwitz, written with the page-turning intensity of a good novel, tells one such story. It expands on Blankfeld’s reporting for The New York Times and Sarah Taksler’s documentary How Saba Kept Singing, which premiered on PBS last April.

The eponymous Saba was David Wisnia, a Polish Jew whose operatic singing voice helped him survive. Wisnia, who died at 94 in 2021 and wrote his own memoir, was a major source for Blankfeld. But, unlike the filmmaker, she accords equal weight to the perspective of Helen “Zippi” Spitzer, a Slovakian Jew who became Wisnia’s lover. Though unable to speak to Spitzer, who died at 99 in 2018, Blankfeld skillfully uses interviews Spitzer gave to Holocaust historians and her unpublished memoir to piece together details of her life.

Lovers in Auschwitz uses a musical vocabulary for its section titles: “Overture,” “Aria,” “Duet,” “Interlude” and “Cadenza.” Spitzer played the mandolin in the camp orchestra, and music was one of her ties to Wisnia.

The protagonists’ travails began well before Auschwitz. As a child, Spitzer lost her mother to tuberculosis. Feisty and determined, she battled both sexism and antisemitism to become a graphic designer. Her brother was imprisoned, and her fiancé eventually executed, for their roles in the anti-fascist resistance.

Wisnia barely survived the Warsaw Ghetto, where his family was murdered. Deported to Auschwitz at 16, he had the smarts to add two years to his age, making himself seem more fit for work. His first assignment — collecting corpses — was arduous and potentially fatal. But after he was called on to sing for the SS, his talent earned him a job disinfecting inmates’ clothing in a building dubbed the Sauna for its warmth.

It was there, at 17, that he first encountered Spitzer, who was about eight years his senior. She was seemingly fearless, friendly, well-dressed, multilingual. Early on, she had been injured in a construction accident and had suffered from malaria, typhus and other illnesses. But her design skills, organizational abilities and, most of all, knack for making the right friends had secured her an enviable office job.

That post afforded her better living conditions, as well as freedom of movement and crucial access to camp records. According to Blankfeld, she used those perks to aid the camp resistance and protect inmates when she could.

At first, Wisnia and Spitzer exchanged just glances and words, then written messages. Over time, they grew bolder. Relying on friendships and bribes, they retreated monthly to a hideaway that allowed for deeper conversations and even physical intimacy.

There were other affairs at Auschwitz, some far more problematic. Blankfeld mentions the romantic entanglement of another Slovakian Jewish prisoner, Helena Citron, with an Austrian SS officer, Franz Wunsch, chronicled in the excellent 2021 documentary Love it Was Not. Music also figured in that story; the film’s title quotes a German song that Citron sang for Wunsch and underlines the ambiguous nature of their relationship.

Blankfeld discusses an even more troubling liaison, between Spitzer’s friend, ally and office mate, Katya Singer, and a particularly sadistic and murderous SS officer, Gerhard Palitzsch. The two lovers were eventually denounced and punished, though Singer survived the war.

Such relationships were, inevitably, transactional. The Spitzer-Wisnia romance was something purer. But it, too, involved a power imbalance. Like a fairy godmother, Spitzer used her position, with its access to camp paperwork, to protect Wisnia. While Blankfeld supplies few details, Taksler’s documentary suggests that Spitzer kept Wisnia from deportation to other camps.

In late 1944, shortly before the camp’s evacuation, the lovers promised to meet after the war at the site of the Jewish Community Center in Warsaw. Each survived the rigors of death marches and the chaos and brutality of other concentration camps. And with a childhood friend of Wisnia’s, Spitzer made her way to Warsaw and waited.

Meanwhile, Wisnia fell in, happily, with a company of American paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division and set his sights on the United States, where two of his aunts were living. To him, Warsaw signified antisemitism, destruction, death. Whatever his feelings for Spitzer, they were dwarfed by his longing for a new beginning. Spitzer waited in vain.

The aftermath of their affair was a series of missed chances. The two could have run into each other at Feldafing, a displaced persons camp in Germany where they each spent time. Instead, they went on to marry others. Connected by a friend, they eventually spoke on the phone, even planned a meeting that never happened. Their lives and feelings remained, for decades, out of sync.

Only on the eve of Spitzer’s death, when she was bedridden and infirm, did they manage a reunion. It seems to have been both heartbreaking and consolatory. In her late 90s, Spitzer apparently was still tormented by Wisnia’s failure to find her after the war. He tried his best to explain. In parting, he sang a Hungarian song that she had taught him, about a prince on a snow-white steed — a prince who, in their case, never arrived. “He reached out for her hand,” Blankfeld writes, “and for one last time they were at peace together.”