How Arnold Schoenberg leapt into the future and created a new musical form

Known for being a cerebral theorist, the composer gave voice to human heartbreak

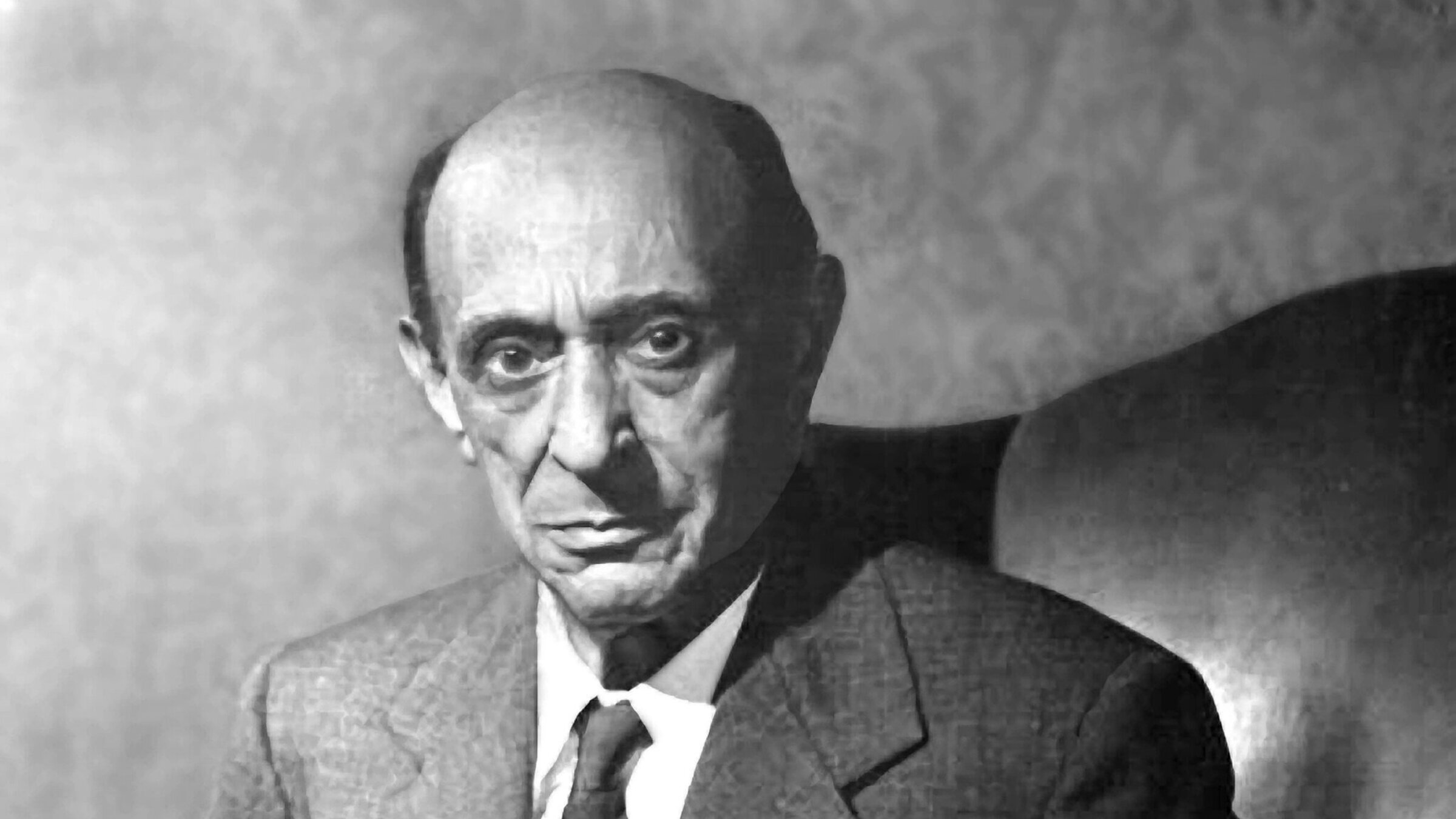

Arnold Schoenberg, 1949. Photo by Getty Images

Forty years ago, a girl in a small Wisconsin town sat by a piano and turned the pages of a song cycle by Arnold Schoenberg for her great-uncle Milton. A local soprano was singing. The setting of 15 poems was the first whole work that Schoenberg based on atonal harmony, which changed Western music and turned him into an icon of Modernist boldness.

The page-turner on that evening of a Jewish family’s Hausmusik was Marilyn Nonken, who now heads the Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions at New York University (NYU). She recalls being “fascinated and scared by the music because it didn’t sound like the music I knew, Beethoven or Mozart. It sounded crazy, like something that would turn people off.”

On Feb. 4, Nonken will join soprano Deborah Norin-Kuehn in a performance of the work — 15 Poems from the Book of the Hanging Garden by Stefan George — to share why it continues to inspire her. The program also includes short early Schoenberg works for solo piano, including a compactly powerful one written for Gustav Mahler’s funeral.

Nonken has become known for performing work by Milton Babbitt and other contemporary composers influenced by Schoenberg (and some who went in other directions). This will be her first time playing the seminal song cycle that transfixed her long ago. “I never had the right singer,” she explained.

Audiences have often had a hard time with Schoenberg’s music, but Nonken stressed that the song cycle, written between 1907 and 1909, relies on his invention of a new musical form but contradicts the popular view of him as a cerebral creator of feelingless abstract systems. When Schoenberg wrote it, he had not yet fleshed out the full 12-tone method that made others who didn’t know better see him as more theorist than artist.

In fact, the cycle embodies Schoenberg’s formal leap into the atonal future while giving new voice to the old human trauma of heartbreak.

Schoenberg wrote the work while his wife, Mathilde, was having a passionate affair with Richard Gerstl, a painter who belonged to his close, inner circle of friends in Vienna. After the relationship was fully exposed, Gerstl killed himself, Mathilde returned to the marriage, and the song cycle has long been associated with the intensity of the episode’s impact on the composer. It clearly sings from tortured internal regions, offering a fragmented allegory about the Garden of Eden and its loss.

“Schoenberg’s personal and creative experience has a lot to say to us today because this music prizes the individual emotional experience;it prizes the depths of human suffering and the richness of engagement with other people,” Nonken said.

Nonken talked about Schoenberg while sitting at the piano in her teaching studio on West 4th Street, turning to the keyboard to play the solo piano works that will be on the program. She also played parts of the song cycle, which swooped from astringent sharpness to haunting tenderness in ways that sounded like an atonal, Germanic blues.

The upcoming program honors the 150th anniversary of Schoenberg’s birth. He was born on September 13, 1874 to a Jewish family in Vienna, where he was raised and lived before moving to Berlin.

Immersed in the antisemitism familiar to European Jews, he converted to Protestant Christianity in 1898. He would later convert back to Judaism in 1933, after Hitler’s rise. In his life of transformations, despite an émigré’s struggle with English, the composer also became an American. He settled in Los Angeles, where he socialized with other Hitler refugees and influenced young American composers.

The upcoming concert is one of several programs NYU has organized as part of a city-wide festival that looks to the past as a warning to the present. Originated by Carnegie Hall, “The Fall of the Weimar Republic — Dancing on the Precipice”runs through May, offering a cross-cultural range of concerts, art exhibits and literary readings of works that show how the arts fed on the anxiety of Germany’s experiment in democracy between the end of World War I and the arrival of a Nazi government in 1933.

There will also be a screening of Der Golem, a 1920 film shaped by the Expressionist sensibility heard in much of Schoenberg’s music. Music students at NYU will perform live music to the film. How the Schoenberg program links to Weimar Republic isn’t obvious, but the works represent the start of a musical revolution that blossomed during the Weimar years.

Nonken had just returned, when we met, from days spent rehearsing the song cycle with Norin-Kuehn at her home in upstate New York. Norin-Kuehn, like Nonken, grew up in a Jewish family from the Midwest, in her case Ohio. They have performed other Schoenberg works for voice and piano together.

Different singers have interpreted the Schoenberg-George song-cycle in widely different ways since it was first performed in 1910. Some have been expansively operatic, others more tenderly intimate. Norin-Kuehn, speaking with me by phone, said that she and Nonken worked toward the latter.

“We focused on the personal intimacy of the piece,” the soprano said. “We are delving into not only the words but the emotion behind every phrase, the way a Method actor might, searching for what motivates that phrase, for the connection you can find within yourself so it is very real.”

There is no openly political content to the works on the upcoming program, but both performers said they were strongly aware of the political context into which the Carnegie Hall Weimar festival places them—the connection between the era just before Hitler took power and the current trends in the United States, including antisemitism.

George, who was not Jewish, was also forced to make painful changes during the Nazi era. Poets knew him for advancing German traditions with complexity and lyricism. But early works conveyed a Nationalist feeling that was embraced by the Nazis. He became a fierce anti-Nazi who turned down a post with Hitler’s government and fled to Switzerland, where he died.

In America, Schoenberg continued to evolve. He grew increasingly open about his passionate Zionism. He composed pieces about the Jewish experience. His uncompleted opera, Moses and Aaron, dates from before he left Europe. Here, he wrote A Survivor from Warsaw, one of the most important works about the horrors of the Holocaust, as well as a setting for Kol Nidre filled with dissonance.

“Sharing his awareness of being a Jew and how that was a very vulnerable position, I think, became more and more important to him as he got older and as the world changed,” Nonken said.

“I do not know if I feel comfortable putting my political stamp on the program,” she continued, reflecting on it as part of the Weimar festival and its spotlight on the fate of democracy. “But Schoenberg sought in his works to exult in the human experience and how the human inner life of the individual matters, and that is political.”