That Passover song about the goat captivated a famous artist who wasn’t Jewish

Frank Stella’s ‘Had Gadya’ series, now at the Skirball in LA, was inspired by a Yiddish picture book

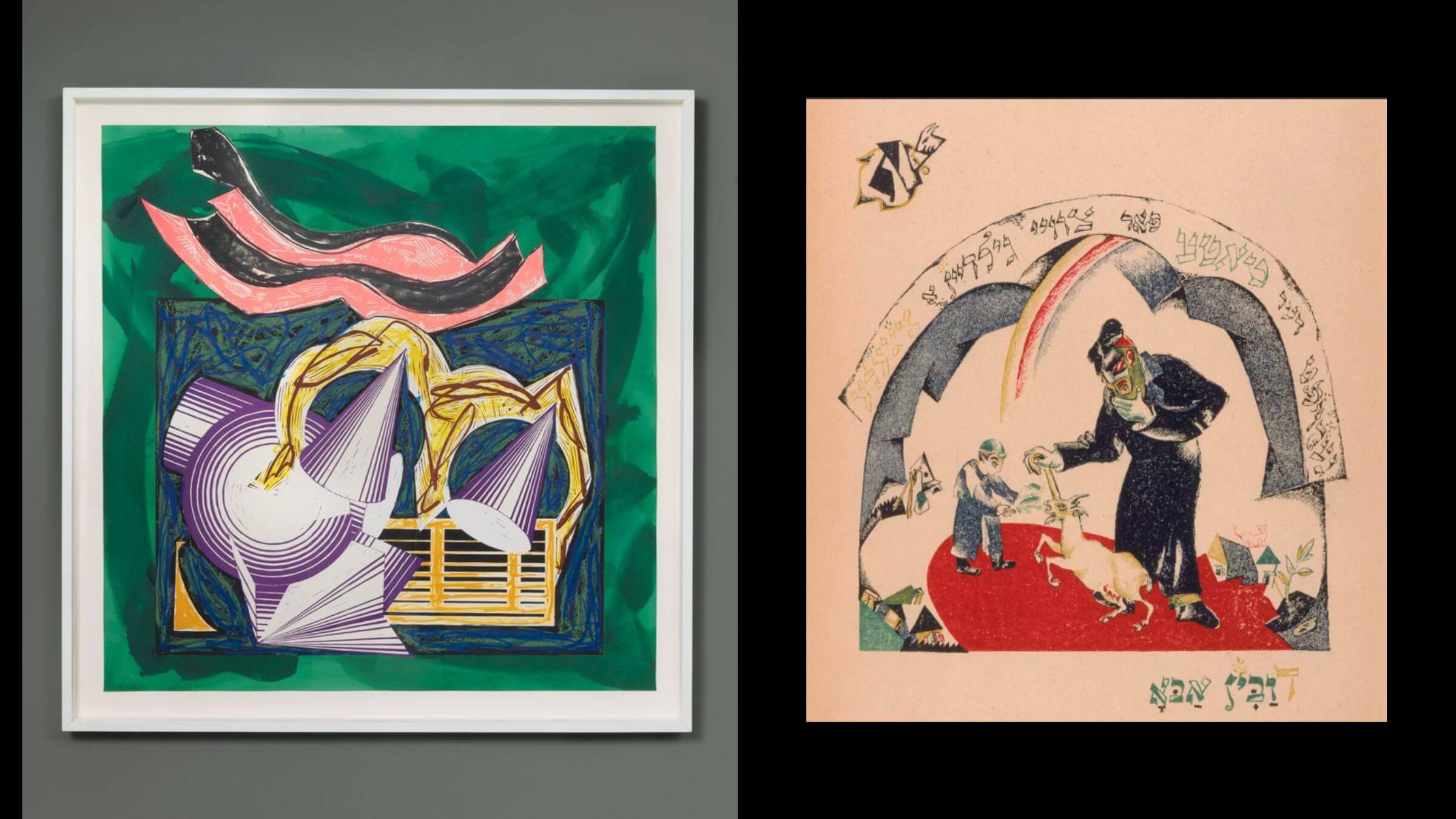

Frank Stella’s One small goat papa bought for two zuzim with El Lissitzky’s Father Bought a Kid for Two Zuzim, on view at the Skirball in Los Angeles. Courtesy of Skirball Cultural Center

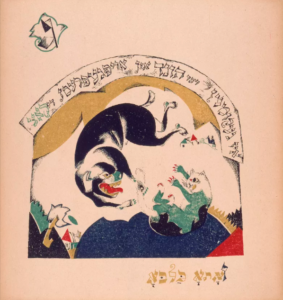

Acclaimed artist Frank Stella grew up in an Italian Catholic immigrant family in Malden, Massachusetts. But a number of his works have Jewish themes — including his colorful illustrations of “Had Gadya,” the beloved Passover song about a little goat.

An exhibition of Stella’s “Had Gadya” series just opened at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. Stella’s work is featured along with his inspiration: the artwork from a Yiddish picture book illustrated by the Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky.

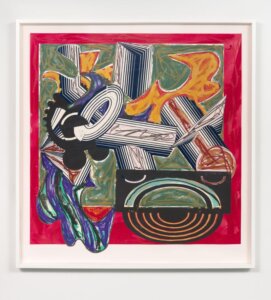

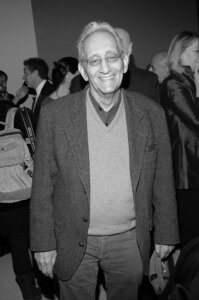

Stella made his own images after seeing Lissitzky’s 11 “Had Gadya” lithographs at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1981. Lissitzky’s pictures, published in 1919, are highly stylized, incorporating elements of Russian folk art as well as cubism, futurism and constructivism. Yet Lissitzky’s images are still recognizable depictions of the goat, cat, dog and other characters from the “Had Gadya” story.

Stella’s versions, in contrast, have few representational references to the song. His interpretations are mostly abstract, with vivid colors, lines and shape. He once explained his philosophy of visual storytelling by saying: “It wouldn’t be a literal story, but the shapes and the interaction of the shapes and colors would give you a narrative.”

The meaning behind the song

“Had Gadya,” Aramaic for “one little goat,” begins with a father buying a goat. It proceeds in a cumulative style — like the nursery rhyme “This Is the House that Jack Built” — building the story line by line while repeating earlier elements. A cat eats the goat, a dog bites the cat, a stick hits the dog, fire burns the stick, water quenches the fire, an ox drinks the water, a butcher kills the ox and the angel of death kills the butcher. Finally, the “Holy One” strikes down the angel of death.

Despite the violent imagery, “Had Gadya” is a lively, whimsical children’s song, sung at the very end of the Seder, perhaps as a way to keep kids and everyone else awake after hours of prayer, food and wine. Its earliest known iteration was in a 14th-century prayer book in Provence, France. Jews expelled from France brought the song to Eastern Europe, where it was published in Aramaic and medieval Yiddish in 16th-century Prague.

The story is seen as an allegory for the survival of the Jewish people despite waves of oppression over the centuries. The Skirball goes a step further, saying in a press release that the song is about “aggressors becoming victims themselves; finally, the cycle is broken through divine intervention — calling our attention to the suffering caused by cyclical violence while holding onto radical hope.”

The Russian artist’s book

Lissitzky’s “Had Gadya” images were published as a book by the Yiddish Kultur-Lige, a project designed to bolster Jewish culture in Ukraine. His colorful, geometric designs include shtetl imagery reminiscent of Marc Chagall, who was his contemporary, as well as Yiddish text. The song’s story also resonated with the plight — and hopes — of Russian Jews before and after the Russian Revolution, when the defeat of czarism heralded a new era.

Stella called Lissitzky’s images “beautifully done, very simple, and very graphic.” He said he saw in the work “something few abstract painters have ever tried to do: address a narrative.”

Stella, now 87, produced 12 of his own images between 1982 and 1984, calling the series Illustrations after El Lissitzky’s ‘Had Gadya.’ The hand-colored collages incorporate lithography, linoleum block and silkscreen techniques. Each one is titled with a line from a verse in the song. While Lissitzky’s pictures are the size of a children’s storybook, measuring about 10 inches by 10 inches, Stella’s are big — 5 feet by 53½ inches.

Jewish themes in Stella’s other work

Among Stella’s most famous works is his groundbreaking 1959 painting titled Die Fahne Hoch!, which means “raise the flag” in German. Those are also the opening words of the Nazi anthem, “Horst-Wessel-Lied.” Stella’s painting appears to show a pinstripe pattern of white lines beneath strips of black, but the white lines are actually blank canvas beneath painted-on black bands. The painting’s flag-like dimensions and dark, rigorous design calls “to mind not only Nazi banners but the darkness and annihilation of the Holocaust,” according to the Whitney Museum, which owns the painting. Stella’s famous comment about the piece, “What you see is what you see,” underscores its importance as a precursor to minimalism.

Stella also did a series of 130 multimedia works called “Polish Village,” inspired by the wooden synagogues of Eastern Europe that were destroyed during World War II. Stella has said that the series commemorated “the obliteration of a culture.”

The Skirball describes Frank Stella: Had Gadya as a “dialogue between two artists of different generations, religious backgrounds, and cultural contexts,” with “Jewish storytelling as a constant source of inspiration for creative expression.” A soundtrack of “Had Gadya” in various languages and musical styles plays in the gallery where the prints are on view. Props are available for visitors to stage their own depictions of the story from the song.

The exhibition was organized in conjunction with the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. On its website, the school says that “Had Gadya” teaches us that the “Angel of Death does not carry the day and, in fact, is destroyed forever. All is not lost.” In fact, the story “beckons us to imagine a better future.” At a time when conflicts between Israel, Hamas and Iran dominate the news, that’s a hopeful way to think about the song and the art it inspired.

The Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles hosts Frank Stella: Had Gadya through Sept. 1.