How a pair of visionary Jews found a link between Jewish and Native American cultures

Even though poet Jerome Rothenberg is gone, his collaboration with composer Charlie Morrow goes on

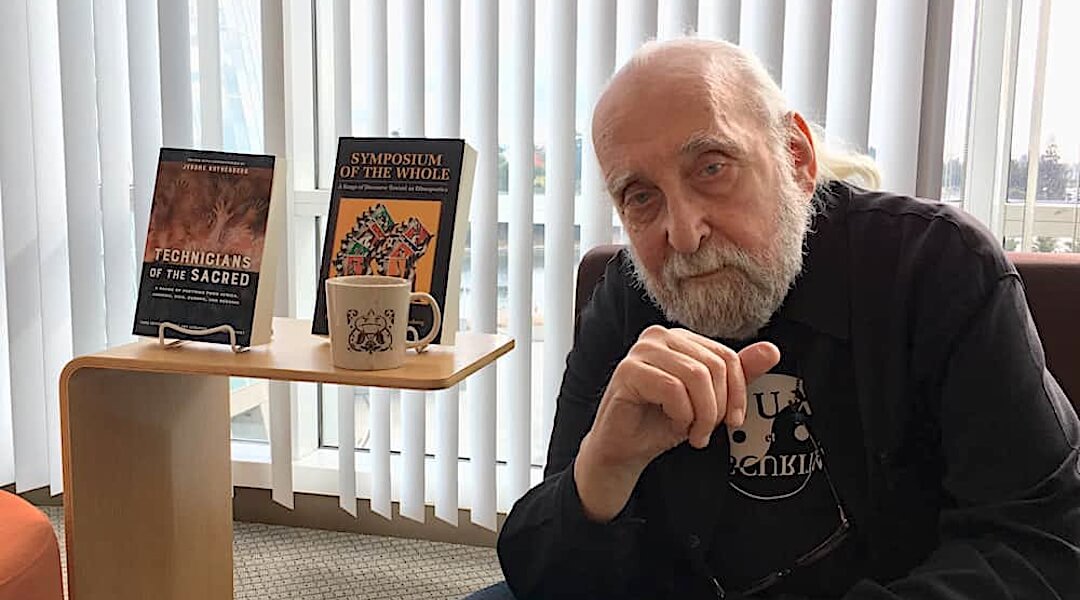

Poet Jerome Rothenberg. Photo by Jon Kalish

For close to 60 years, the poet Jerome Rothenberg collaborated with the composer Charlie Morrow, creating avant-garde art that mined both their Jewish roots and the deep connection to the Indigenous world they shared. After Rothenberg passed away in late April at the age of 92, it would seem that partnership has come to an end.

But Morrow is planning to set some of Rothenberg’s poetry to music posthumously. “There is no end to our long collaboration,” he declared.

The composer is hopeful that their most recent collaboration, an opera titled Abulafia Visits The Pope, will find an audience after a staged reading May 25 at the University of California, Irvine.

“Jerome’s work is luminous and it will be meaningful to people in future generations,” said Morrow, 82, who divides his time between Helsinki, Finland and the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont.

The opera is based on the true story of the Spanish Kabbalist Abraham Abulafia traveling to Rome in the year 1280 hoping to get Pope Nicholas III to switch teams, as it were, on the day before Rosh Hashanah. Rothenberg wrote the libretto in 2011. Morrow composed the score soon thereafter. The work has never been performed before an audience. (Spoiler alert: Abulafia’s plan to spend yontif with the Pontiff did not work out. The Pope reportedly died from an apoplectic stroke and Abulafia was imprisoned briefly, later surfacing in Sicily, where he claimed to be the messiah. That, too, did not pan out.)

Where Yiddishkeit meets the Senecas

Rothenberg and Morrow met at the Mannes School of Music in the early 1960s, when Rothenberg was teaching in the school’s English department and Morrow was pursuing a diploma in trumpet and composition.

In addition to creating sound art together, Morrow served as Rothenberg’s sideman, playing ocarina, conch shell, shofar, cow’s horn, Jew’s harp or pocket trumpet. They performed and recorded together in the U.S. and abroad. Their last performance took place in March 2022 in London.

Both tapped into Yiddishkeit for artistic grist but Rothenberg drew his friend into the Indigenous world as a source of creative inspiration. It began in 1968 when Morrow recorded Rothenberg performing Navajo horse songs. Seventeen of them were sent to Rothenberg by David McAllester, a Wesleyan University ethnomusicologist.

The horse songs involve a mythical figure known as Enemy Slayer. According to Navajo legend, Enemy Slayer fetches magical horses from the sun. McAllester sent Rothenberg transcriptions and recordings of horse songs performed by a Navajo singer in Arizona named lta’í Tsoh (“Big Schoolboy,” English name Frank Mitchell).

Rothenberg also devoted himself to translating songs and poems of the Seneca people in western New York.

Tribal peoples

An anthropologist named Stanley Diamond who had done research at the Seneca Nation urged Rothenberg to go out in the field like an anthropologist.

Rothenberg, his wife, Diane, and their young son, Matthew, initially visited the Seneca Nation’s Allegany Territory during the Christmas holiday in 1967. They returned a month later for the tribe’s mid-winter ceremonies and decided to spend the summer of 1968 with the Seneca, who live about 60 miles south of Buffalo, N.Y. Rothenberg worked on translations of Seneca poems and songs while he and his family lived in a converted gas station. Matthew Rothenberg, who was three at the time, remembers that the yard behind the gas station was full of snakes.

The Rothenbergs visited the Seneca territory frequently during 1969 while Diane Rothenberg was pursuing an anthropology degree. In 1972 the family came back for a two-year stay during which Diane worked on her doctoral dissertation. Jerome worked on A Big Jewish Book, a 600-page anthology of Jewish poetry.

“That seemed like the perfect thing to be doing there,” he joked in the 2005 documentary The Bard of Encinitas.

Rothenberg became close with Seneca singers and song-makers, including Richard Johnny John, whose Seneca name was Onöhsagwë:de’. A sprawling Seneca cultural center in Salamanca, N.Y., was named after him. According to Diane Rothenberg, in summer 1972 she and her husband were adopted, he into the Beaver Clan with the Seneca name Haiwano (“Keeper of the High Words”), she into the Blue Heron Clan. Both adoptions were unofficial acts intended to honor outsiders, so the Rothenbergs were not entitled to a share of the casino earnings or cigarette taxes.

A Seneca elder named Marcia Abrams in Steamburg, N.Y., remembers the poet.

“Jerome came around here quite often,” Abrams, 83, recalled. “He had a lot of friends here.”

“The Seneca recognized us as Jews, as tribal people,” Diane Rothenberg told me after her husband’s passing. “I don’t know if [Jerome] got as much of a kick out of it as I did.”

The anxiety of influence

Rothenberg’s best known work is Technicians of the Sacred, which he described as “an anthology of tribal, oral poetry with a lot of emphasis on performance.” It elevated ancient chants and incantations as poetry on par with the Western literary canon. Still in print more than half a century after its initial publication, the anthology struck a chord with Jim Morrison of The Doors, who is said to have been buried with a copy.

Crystal Zevon, widow of Warren Zevon, said that when he moved in with her in 1971, Technicians of the Sacred was the only book he brought with him. Nick Cave of The Bad Seeds and Eugene Hütz of Gogol Bordello both were profoundly moved by the anthology.

“Jerome insisted that Indigenous cultures were just as complex as Western ones and their art was just as great,” Charles Bernstein, a poet and friend of Rothenberg, told me.

Rothenberg’s championing of ancient poetics did receive pushback. After he co-edited an anthology of American poetry that included pre-Columbian Time verse, the New York Times poetry critic Helen Vendler panned the book. Vendler, who passed away two days after Rothenberg, wrote in a December 1973 review: “Back to primitive roots we go — to runes, inscriptions, charms, riddles, spells, catalogues, invocations … baby-talk … and, we hope, the pristine unfallen vision of man, merely himself, before the corruption of high culture.”

Some Native intellectuals also had a problem with work like Rothenberg’s and denounced it as “white shamanism.”

Rothenberg and Morrow collaborated in 1970 on 66 Songs for a Blackfoot Bundle. If it was performed today, said Morrow, the piece would likely come under fire for cultural appropriation. (A Native American bundle is a collection of sacred items that are believed to have the power to heal people. Native Americans considered the contents a gift from the Creator.)

A bundle is mentioned in Poland/1931, a collection of Rothenberg’s poems set in the land of his parents’ birth during the year he was born. In one of the poems Rothenberg transposes the Baal Shem Tov to the 19th-century American West, where the founder of the Hasidic movement is found riding a horse through Indian country.

a jew among

the indians

vot em I doink in dis strange place

mit deez pipple mit strange eyes

could be it’s trouble

could be could be

Later in the poem, Rothenberg writes: “when the Baal Shem (yuh-buh) learns to do a bundle what does the Baal Shem (buh-buh) put into the bundle?”

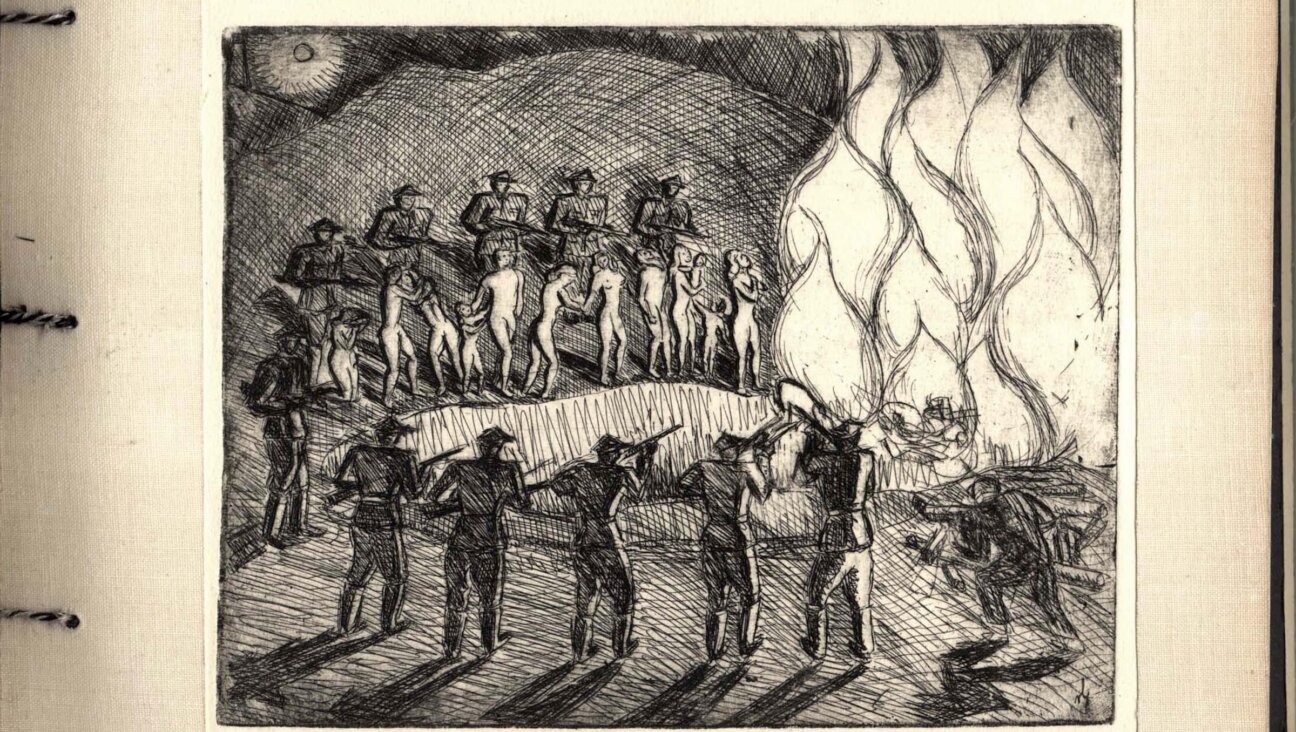

In The Bard of Encinitas Rothenberg recalled seeing a photo of a thin and gaunt Native man who reminded him of Nazi death camp survivors. Rothenberg said that when the man was asked his name, he responded, “Ishi,” the word for person or man in the language of an Indigenous group known as the Yana. The linguistic coincidence was not lost on Rothenberg: The Hebrew word for man is ish. He remarked in the documentary that the Yana Indians, like the Jews, had been exterminated.

Morrow and Rothenberg’s meeting came at a pivotal time in Morrow’s life. After graduating from Columbia, Morrow decided not to go to medical school, much to the disappointment of his parents, who were both psychiatrists. Instead, he went to Mannes to pursue a career in music. His mother may have been disappointed but nevertheless lent him the cash to buy a four-track reel-to-reel tape deck, which Morrow wanted to record Rothenberg performing the Navajo horse songs.

That recorder was the foundation of Morrow’s first studio, and in the years that followed he would prove to be an early adopter of innovative audio technology, embracing world music and digital sampling as a jingle composer and pioneering a 3D sound system used today everywhere from hospitals to retail stores.

Morrow was dubbed Weird Time Charlie in a 1980 Advertising Age profile because he produced such wacky avant-garde events as a Concert for Fish on a bay in Queens and Toot’n Blink with fleets of boats on Lake Michigan. Those after hours events were organized while the composer was penning memorable jingles for Windsong perfume (“I can’t seem to forget you / your Windsong stays on my mind.”), Hefty garbage bags (“Hefty, Hefty, Hefty / Wimpy, Wimpy, Wimpy”) and the MTA’s JFK Express (“Take the Train to the Plane”).

A shaman in New York

Decades ago, while Morrow was still living in New York City, he began to describe himself as a shaman. More and more, Morrow’s musical compositions were built around his own voice. He acknowledges that Rothenberg inspired him to find his “chanting voice.”

Morrow visited the Rothenbergs at least four times while the family was living in the Seneca Nation. He attended community singing and Longhouse events and met the Seneca song men Richard Johnny John and Avery Jimerson. The latter performed in Manhattan in the mid-1970s thanks to his connection to Morrow and Rothenberg. Morrow’s exposure to the Seneca musical tradition had a marked effect on the composer’s creative path in the years that followed, said Rothenberg.

“A big portion of his work for a few years was centered on chanting in the manner of the American Indian chants or tribal chants from other parts of the world,” Rothenberg told me in a 2010 interview. “I don’t think he could’ve gotten into that without some degree of contact” with the Seneca.

Morrow has been chanting since his bar mitzvah. Sometimes he plays a hand-held gong while he chants. Often his chants are based on his dreams, and he has been told that his dream songs sound like yoiking, the traditional a cappella singing of the Indigenous people known as the Sámi, in Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

In 1974, Morrow and Rothenberg founded the New Wilderness Foundation, which produced audio cassettes of sound art, as well as traditional and experimental music. One of the New Wilderness recordings featured the Native American activist Leonard Crow Dog and his wife singing peyote songs. (Crow Dog played a key role in the American Indian Movement takeover of a South Dakota town in 1973.) Another New Wilderness cassette featured the Seneca song-maker Avery Jimerson.

Morrow has had a continuing collaboration with Indigenous people in the Arctic. He composed the score for a 1988 feature film about a Sámi boy in modern Sweden who goes to live with his grandfather, a reindeer herder in Lapland. Morrow has also worked with the Sámi yoik singer Asa Simma, who heads the Sámi national theater. She participated in Morrow’s winter solstice celebration in December 2020.

Morrow has organized a series of events that will take place in Finland during October. They include an art gallery installation on small Arctic boats and a 13-hour bus ride from Helsinki to hear Arctic sounds.

Next month the German record label VOD will release an 11-LP vinyl boxed set of audio recordings from the New Wilderness years that feature a number of Rothenberg and Morrow pieces, as well as a substantial number of Native American selections. Also coming in June is a Tzadik Records album, In the Shadow of a Mad King, which will feature Rothenberg reading his poems on the Trump era with musical accompaniment by the bassist Mark Dresser. The last of Rothenberg’s anthologies will be published in the fall.