He’s named after his grandfather Alfred Dreyfus (not that one)

How a note on a grave sparked a decadeslong friendship

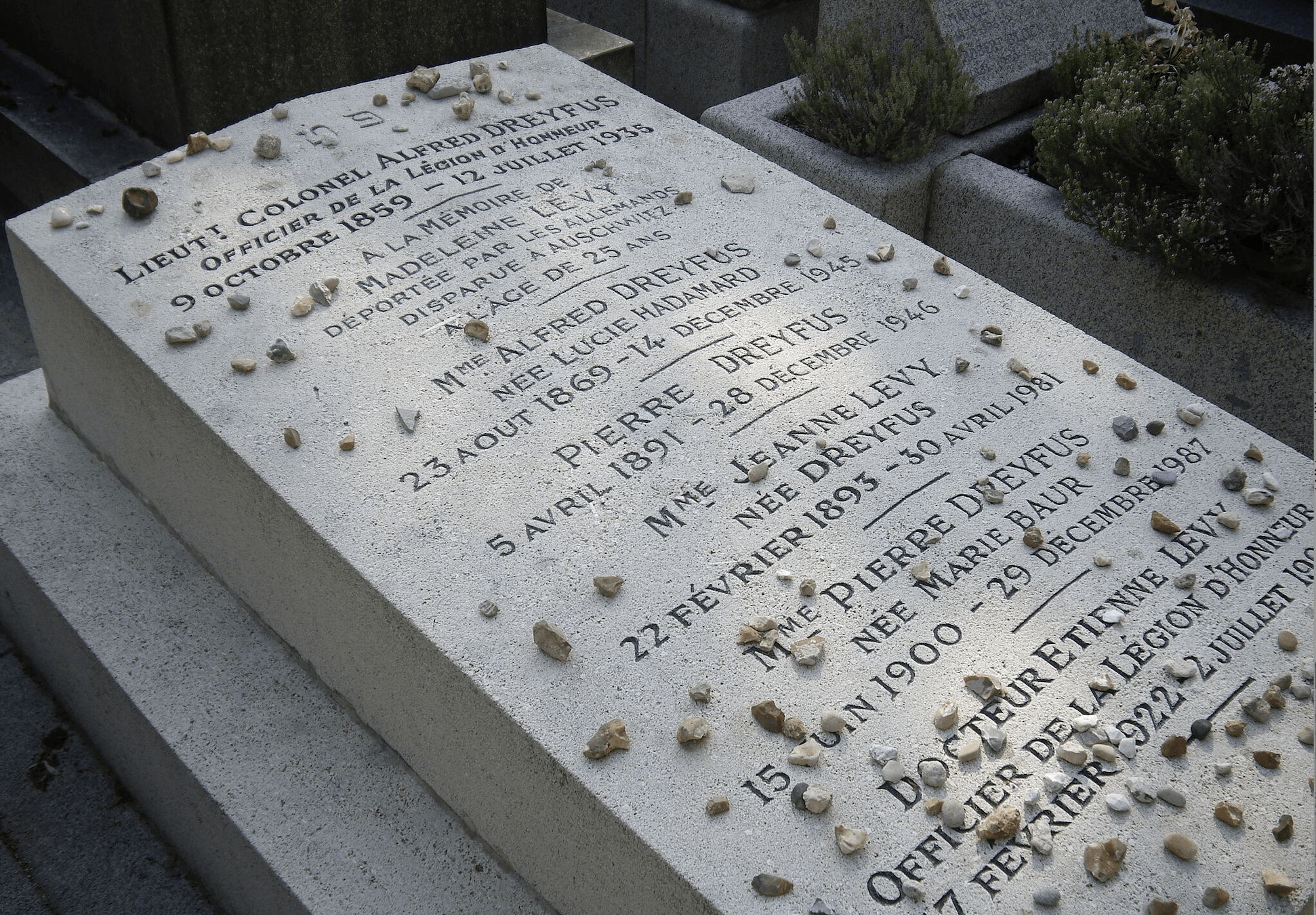

The tomb of Alfred Dreyfus, where Alfred Dreyfus Samuelson left his business card. Photo by Mu via Wikimedia Commons

It is common for visitors to the grave of Alfred Dreyfus, the wrongfully convicted French-Jewish officer, to leave a stone. One man left a business card.

25 years ago in the Montparnasse Cemetery, the chief of staff for Democratic Senator Tim Johnson of South Dakota, placed the card beneath a small stone at the grave’s base with the note, “My name is actually Alfred Dreyfus Samuelson, and I’m named after you!”

Samuelson goes by Drey (pronounced “like Dr. Dre only much less rich”). He has, understandably, had a lifelong fascination with his namesake and his 12-year persecution by an antisemitic French society that charged him with treason. Samuelson put down his card in a sentimental moment, but a few weeks later he got a call from Paris. On the other line was Dreyfus’ great-grandson Jean-Marc Perl.

Perl’s mother found the card, but wasn’t fluent in English, so asked him to investigate. A week after connecting, Perl and Samuelson got lunch in New York, where Perl did business for his work in the clothing industry. They’ve been friends ever since and, in mid-May, spent a few days together at Perl’s vacation home in Normandy.

Unlike the Dreyfus Affair, whose 1906 resolution, exonerating the captain, is accepted by all but a few stubborn conspiracy theorists, who Dreyfus’ descendants work to combat, the mystery of Samuelson’s given name isn’t settled history.

“I grew up in a little farm town of 1,000 people in Nebraska,” said Samuelson, 71. “I’m actually named after my grandfather, who was born in 1899.”

His Danish great-grandparents were likely following the Dreyfus Affair, an international cause célèbre that in 1899 had reached a retrial. By that time, much of the world was convinced of Dreyfus’ innocence — and who could be more innocent than a newborn? At least, that was Samuelson’s mom’s theory. His awareness of Dreyfus, who wasn’t a political figure by choice, partly inspired Samuelson’s career in politics.

“Part of my family believes that my great-grandfather, who named my grandfather, was actually a Jew who went underground because of antisemitism,” said Samuelson, but two different DNA tests failed to find Jewish ancestry.

“Nobody’s perfect,” Perl, 77, joked, sitting next to Samuelson during a Zoom call from Normandy.

Unlike many of the Dreyfus heirs, Perl’s family is still Jewish.

“Drey is named Dreyfus, but he’s not Jewish. My name is not Dreyfus, but I am Jewish,” said Perl.

The two men have kept in touch for 25 years over email and, when they are on the same continent, they share meals and discuss Dreyfus’ story, which still resonates 118 years later. (The first time they met for lunch was with Samuelson’s then-wife Lucy; Captain Dreyfus’ wife was named Lucie. In another odd coincidence, Samuelson’s brother is named Matthew; Mathieu was Dreyfus’ devoted brother who fought to clear his name.)

Perl said that, while his ancestor was a victim of the right-wing antisemitism of high society, today he feels this bigotry is coming from the “extreme left,” recalling a recent radio interview with a young man who dismissed the Holocaust as something that didn’t matter to him, because he hadn’t been born yet.

But the Dreyfus Affair remains a point of interest in France, where it is included in textbooks. Politicians like Jacques Chirac and Emanuel Macron have held conferences and ceremonies. Perl said certain powerful people are now pushing to award Dreyfus, whose military career was derailed by his trials and imprisonment and who ended his service as a lieutenant colonel, the posthumous rank of general.

Perl believes it’s too little, too late. “It would be magnificent if he would have been named a great general when he was alive.”

Alfred Dreyfus Samuelson, while not strictly a member of the Dreyfus family, is keeping the family name alive.

“If they would have named me ‘John Smith’ or something, that would be meaningless,” said Samuelson. But being named for someone who was persecuted, and endured his ordeal with dignity, helped to guide him in life.

“I think that whetted my appetite for social justice and for trying to make the world a better place,” Samuelson said.