A hauntingly bizarre musical upends Stephen Sondheim’s signature maxim — here, everyone is alone

In Dave Malloy’s COVID-era ‘Three Houses,’ a brilliant structure saves three little pigs but leaves audience out in the woods

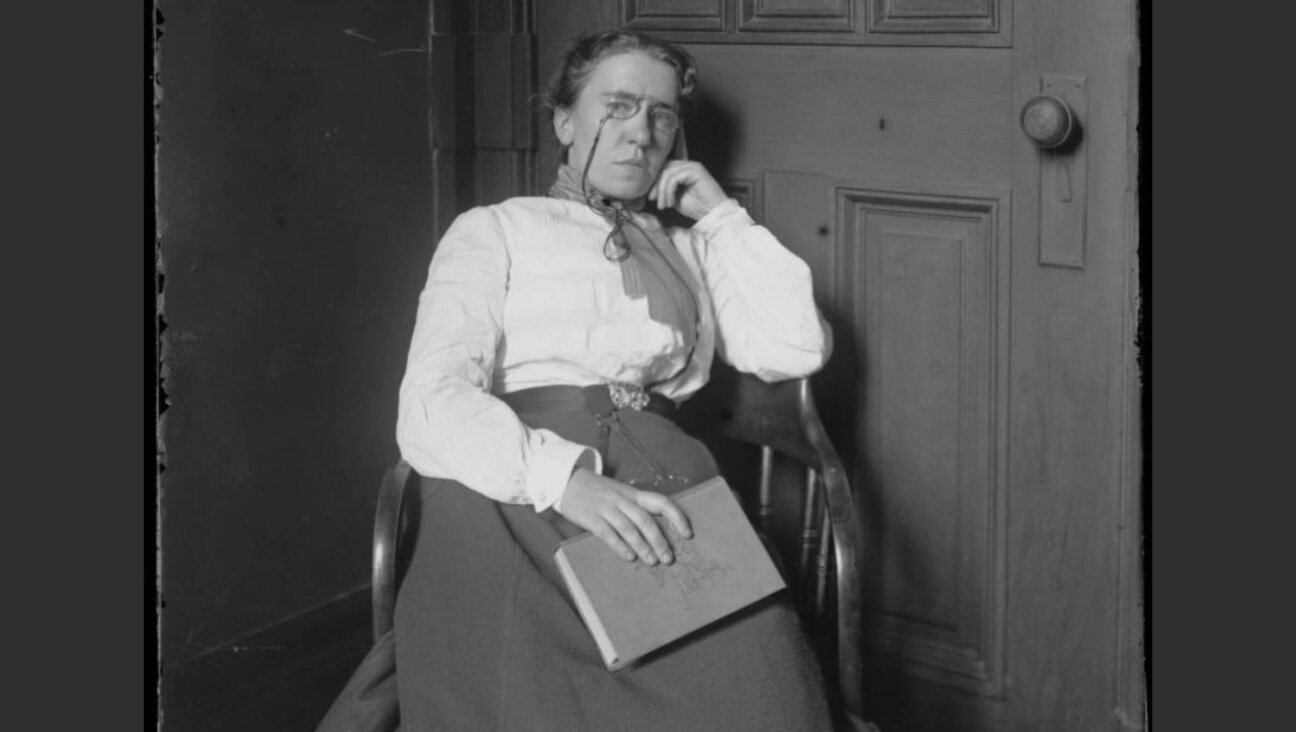

Mia Pak, Margo Seibert and a puppet companion in Three Houses. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

At first glance, Dave Malloy’s oeuvre looks a little like a series of dares. Best known for supplying book, music, lyrics (and orchestrations) for Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 — his Broadway debut, adapted from a 70-page sliver of War and Peace — Malloy had an equally ambitious pre-pandemic year; in 2019, he adapted Moby-Dick at Harvard’s American Repertory Theater, and created the much-lauded, brain-explosion-emoji-warranting Octet, the first musical to premiere at Signature Theatre in Manhattan since its founding in 1991. The latter, inspired by the 22 cards in a Major Arcana tarot deck, was an a capella musical set at a support group for internet addicts (I know, astounding that no one beat him to the punch on that one). Octet launched Malloy’s historic five-year residency at Signature.

Thus, it should surprise no one that, in Malloy’s second outing at the Sig, alongside director Annie Tippe (with whom he previously collaborated on Octet and 2014’s Ghost Quartet), he has continued his streak of staging the seemingly unstageable, this time with Three Houses, a karaoke bar confessional about lockdown-era isolation. Yet again, Malloy draws upon an unexpected source — “The Three Little Pigs.” You know the story: The titular characters’ houses are made of various materials; a Big Bad Wolf huffs and puffs, successfully destroying the houses of the first two, made of straw and sticks, respectively, but pig number three, with their sturdy brick abode, ultimately reigns victorious.

This musical triptych sees its protagonists — Susan, Sadie and Beckett — looking back on their early days of lockdown in Latvia; Taos, New Mexico; and Brooklyn. One by one, they take the mic, with the help of libations served by a bartending Wolf (Scott Stangland) — wittily, with a straw, a swizzle stick, and, finally, in a forced-and-inexplicable-but-we’re-going-to-break-the-fourth-wall-to-acknowledge-it moment of narrative necessity, a brick.

As they descend into pandemic madness, the protagonists each either reference and/or display characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. (As someone with OCD, I can attest to the accuracy of the depiction of the nightmarish exacerbation of symptoms that coincided with the lockdown.) Susan fixates on organizing the bookshelf at her late grandmother’s forest ranch; Sadie devotes 14 hours a day to an online “life-simulation” game, seeking to reconstruct her grandparents’ Ohio ranch; and Beckett attempts to self-isolate via using his endless supply of Amazon boxes to construct a clochán (“A house made of stone where I can’t hurt anyone / A house made of stone where I can’t get hurt”). Each character is accompanied, taunted, enabled, and sometimes tormented by cute-but-creepy puppet companions — Pookie, a mythical Latvian house dragon; Zippy, a video game badger; and Shelob, a house spider (puppets are by James Ortiz).

There is much to admire in the characters’ Sondhemian complexity of thought (though, dear reader, I grant you my blessing to roll your eyes at such an allusion). And I imagine that many viewers will find the characters’ spirals to be relatable, even cathartic. At the same time, though, I found the musical’s emotional impact to be blunted by the intellectualism of its constricting narrative architecture (and, as Grandfather, played by national treasure Henry Stram, reminds us, “‘The Three Little Pigs’ isn’t about architecture, you know”).

Each musical vignette begins with its central character hopeful and expectant, preparing to revel in “the joy and simplicity of being alive.” Soon, though, their world begins to shake on its axis, until they find a melancholy sense of purpose and wisdom through connection to their grandparents, all played by Stram and the equally delightful (and legendary) Ching Valdes Aran.

The similarities between the vignettes don’t end there: Each character texts with their J-initialed ex (Julian, Jasmine, and Jackie)— “just checking in, are you OK?” And each possesses an alcoholic octet (maybe coincidence, maybe an Easter egg of sorts) — first, jugs of red currant wine, then cases of mezcal stashed away in the basement, and, finally, bottles of plum brandy (accrued through contactless delivery).

I tend to be endlessly satisfied by a perfect symbiosis between content and form. And certainly, the musical’s redundant, Groundhog Day vibe feels thematically apropos and — theoretically — brilliant. Three Houses appears to be a parable of sorts about the desperate and destructive measures to which we resort in pursuit of control when everything seems to fall apart. But the fatal flaw of its central trio — their implacable need to seek order, no matter how inexorable the chaos that surrounds them — seems to mirror that of the musical itself, diluting its Malloy-esque existentialism.

Fairytales and fables are designed to simplify and synthesize the nuanced and inconsistent realities of being human into a digestible moral. And, while this framing enables Malloy to interrogate the near-universal pandemic experience of loneliness and stagnancy, the template diminishes the complexity and insight exhibited in his earlier works. Typically, Malloy is fearless and unbridled in musicalizing the weird and the ugly — but the self-imposed structure demands containment. There’s a reason, after all, why librettist James Lapine and the aforementioned superstar composer-lyricist killed off the Narrator in Into the Woods. And, in the case of Three Houses, despite the messiness of his characters’ psyches, Malloy — dramaturgically — keeps it all too clean.

Still, inarguably, there are moments of divinity in Three Houses, many of which are aided by its visual splendor. Christopher Bowser’s lights are hypnotic and the set — by the ever-inspired design collective Dots — exquisitely captures Malloy’s hauntingly bizarre sensibility. Buttressed by some of Malloy’s most incisive and gutting poetry yet, Sadie’s “Haze,” in which a devastatingly earnest Mia Pak sings “Sometimes it feels like this is not my life / but someone else’s life. / A phantom pantomime / of my true life. / And I don’t know how to get back,” is sure to elicit the adoration of the scribe’s most ardent devotees. For anyone who has not previously been initiated into Malloy’s work and longs for the kind of musical that transcends banal commerciality, Three Houses is a must-see simply for the opportunity to marvel at the vastness of its creator’s byzantine brain.